(Press-News.org) A team led by researchers at National Jewish Health has discovered a new genetic variation that increases the risk of developing pulmonary fibrosis by 7 to 22 times. The researchers report in the April 21, 2011, issue of The New England Journal of Medicine that nearly two-thirds of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or familial interstitial pneumonia carry the genetic variation. It is associated with the MUC5B gene, which codes for a mucus-forming protein.

"This discovery not only identifies a major risk factor for pulmonary fibrosis, but also points us in an entirely new direction for research into the causes and potential treatments for this difficult disease," said Max Seibold, PhD, first author and research instructor at National Jewish Health and the Center for Genes, Environment and Health. "The research also demonstrates how a genetic approach to disease can uncover a previously unknown and unsuspected association disease."

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and familial interstitial pneumonia (FIP) are similar, invariably fatal diseases that involve progressive scarring of the lungs. The scarring prevents oxygen transport to the tissues, and most people die of respiratory failure within a few years of diagnosis. The diseases are relatively rare, but account for approximately 40,000 deaths each year, the same number as die of breast cancer. There is no approved treatment for the diseases.

Research into pulmonary fibrosis has been quite difficult. Little is understood about the biological roots of the diseases, and recent clinical trials of several experimental medications have failed to effectively treat them. Previous research has focused primarily on the scarring and inflammatory processes evident in the disease.

In the study funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Jewish Health researchers and their colleagues took an "agnostic" approach, statistically analyzing the entire genome of 82 afflicted families. They found an association with the diseases in a region of chromosome 11 that contains four mucin genes involved in the production of mucus. Narrowing their search with fine mapping, then sequencing, they eventually found a common variation near the MUC5B gene, presumably in a regulatory element, that is strongly associated with the disease.

"This research suggests that mucus production where the small airways and the air sacs converge may play a significant role in pulmonary fibrosis," said senior author David Schwartz, MD, Chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Director of the Center for Genes, Environment and Health at National Jewish Health.

The variation exists in 19 percent of healthy controls, 59 percent of FIP patients, and 67 percent of IPF patients. Carrying one copy of the gene increases the risk of developing FPF by 6.8 times, and IPF by 9.0 times. Carrying two copies of the variation increases risk 20.8 times and 21.8 times, respectively.

The researchers discovered that the genetic variant increases production of MUC5B more than thirtyfold in unaffected patients. They also found that MUC5B production is elevated in pulmonary fibrosis patients both with and without the gene.

"There are several biologically plausible ways in which excess mucus could cause disease," said Dr. Schwartz. "We are currently investigating all of these mechanisms as potential causes of disease."

Mucus is a vital part of lung biology, protecting delicate cells from direct exposure to inhaled irritants and toxins, and helping to clear them from the lungs. The researchers hypothesize that excess mucus production caused by the MUC5B variant could slow clearance of mucus contaminated with irritants and toxins. Excess mucus might also interfere with repair of air sacs damaged by these contaminants. Another scenario suggests that the genetic variation could trigger the production of mucus in areas where it is not normally present. In addition to National Jewish Health, other institutes contributing to this study were the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Colorado School of Public Health, Duke University Medical Center, North Carolina State University, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Landspitali University Hospital, in Reykjavik, Iceland, the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, the University of Miami, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

INFORMATION:

National Jewish Health is known worldwide for treatment of patients with respiratory, cardiac, immune and related disorders, and for groundbreaking medical research. Founded in 1899 as a nonprofit hospital, National Jewish Health remains the only facility in the world dedicated exclusively to these disorders. Since 1998, U.S. News & World Report has ranked National Jewish the #1 respiratory hospital in the nation.

END

STANFORD, Calif. — A class of engineered nanoparticles — gold-centered spheres smaller than viruses — has been shown safe when administered by two alternative routes in a mouse study led by investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine. This marks the first step up the ladder of toxicology studies that, within a year and a half, could yield to human trials of the tiny agents for detection of colorectal and possibly other cancers.

"These nanoparticles' lack of toxicity in mice is a good sign that they'll behave well in humans," said Sanjiv Sam Gambhir, MD, ...

CLEVELAND-Your 6-year-old found a nail in the garage and drew pictures across the side of your new car.

Gnash your teeth now, but researchers at Case Western Reserve University, U.S., say the fix-up may be cheap and easy to do yourself in the not-too-distant future.

Together with partners in the USA and Switzerland, they have developed a polymer-based material that can heal itself when placed under ultraviolet light for less than a minute. Their findings are published in the April 21 issue of Nature.

The team involves researchers at Case Western Reserve University ...

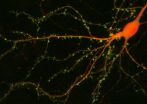

A team of neuroscientists at the University of Leicester, UK, in collaboration with researchers from Poland and Japan, has announced a breakthrough in the understanding of the 'brain chemistry' that triggers our response to highly stressful and traumatic events.

The discovery of a critical and previously unknown pathway in the brain that is linked to our response to stress is announced today in the journal Nature. The advance offers new hope for targeted treatment, or even prevention, of stress-related psychiatric disorders.

About 20% of the population experience some ...

Summer is as good reason as any to look fabulous, whether with a full-on bright look or with a bold accessory. Go for the coveted sun-kissed, vivid Summer look with a crayon box explosion of color from Boden. From colorful kaftans to shiny shoes, the new Summer collection will brighten your look, cheer up your wardrobe and put a smile on those around you.

Be beautiful and feel like a modern princess with Piazza Dress. The neck detail worthy of Cleopatra and the natural slubbiness of silk make it uniquely alluring. Top your dress off with the Printed Silk Scarf, its light-weight ...

Scientists at Imperial College London and the University of Washington, Seattle, have taken an important step towards developing control measures for mosquitoes that transmit malaria. In today's study, published in Nature, researchers have demonstrated how some genetic changes can be introduced into large laboratory mosquito populations over the span of a few generations by just a small number of modified mosquitoes. In the future this technological breakthrough could help to introduce a genetic change into a mosquito population and prevent it from transmitting the deadly ...

Current UK procedures to screen new immigrants for tuberculosis (TB) fail to detect more than 70 per cent of cases of latent infection, according to a new study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

TB is caused by a bacterial infection which is normally asymptomatic, but around one in 10 infections leads to active disease, which attacks the lungs and kills around half of people affected.

Today's research showed that better selection of which immigrants to screen with new blood tests can detect over 90 per cent of imported latent TB. These people can be given ...

Infants who have problems with persistent crying, sleeping and/or feeding – known as regulatory problems – are far more likely to become children with significant behavioural problems, reveals research published ahead of print in the journal Archives of Disease in Childhood.

Around 20% of all infants show symptoms of excessive crying, sleeping difficulties and/or feeding problems in their first year of life and this can lead to disruption for families and costs for health services.

Previous research has suggested these regulatory problems can have an adverse effect ...

Children from homes that experience persistent poverty are more likely to have their cognitive development affected than children in better off homes, reveals research published ahead of print in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Family instability, however, makes no additional difference to how a child's cognitive abilities have progressed by the age of five, after taking into account family poverty, family demographics (e.g. parental education and mother's age) and early child characteristics, UK researchers found.

There is much evidence of the ...

In the past 12 years, four large-scale efficacy trials of HIV vaccines have been conducted in various populations. Results from the most recent trial—the RV144 trial in Thailand, which found a 31 percent reduction in the rate of HIV acquisition among vaccinated heterosexual men and women—have given scientists reason for cautious optimism. Yet building on these findings could take years, given that traditional HIV vaccine clinical trials are lengthy, and that it is still not known which immune system responses a vaccine needs to trigger to protect an individual from HIV ...

Imagine you're driving your own new car--or a rental car--and you need to park in a commercial garage. Maybe you're going to work, visiting a mall or attending an event at a sports stadium, and you're in a rush. Limited and small available spots and concrete pillars make parking a challenge. And it happens that day: you slightly misjudge a corner and you can hear the squeal as you scratch the side of your car--small scratches, but large anticipated repair costs.

Now imagine that that you can repair these unsightly scratches yourself--quickly, easily and inexpensively. ...