(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

Artificial skin for people and robots could be a reality using the ultra-sensitive sensors developed by Zhenan Bao, associate professor of chemical engineering at Stanford University, and her team. The...

Click here for more information.

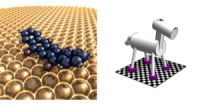

The light, tickling tread of a pesky fly landing on your face may strike most of us as one of the most aggravating of life's small annoyances. But for scientists working to develop pressure sensors for artificial skin for use on prosthetic limbs or robots, skin sensitive enough to feel the tickle of fly feet would be a huge advance. Now Stanford researchers have built such a sensor.

By sandwiching a precisely molded, highly elastic rubber layer between two parallel electrodes, the team created an electronic sensor that can detect the slightest touch.

"It detects pressures well below the pressure exerted by a 20 milligram bluebottle fly carcass we experimented with, and does so with unprecedented speed," said Zhenan Bao, an associate professor of chemical engineering who led the research.

The key innovation in the new sensor is the use of a thin film of rubber molded into a grid of tiny pyramids, Bao said. She is the senior author of a paper published Sept. 12 online by Nature Materials.

Previous attempts at building a sensor of this type using a smooth film encountered problems.

"We found that with a very thin continuous film, when you press on it, the material does not have room to expand," said Stefan Mannsfeld, a former postdoctoral researcher in chemical engineering and a coauthor. "So the molecules in the continuous rubber film are forced closer together and become entangled. When pressure is released, they cannot go back to the original arrangement, so the sensor doesn't work as well."

"The microstructuring we developed makes the rubber behave more like an ideal spring," Mannsfeld said. The total thickness of the artificial skin, including the rubber layer and both electrodes, is less than one millimeter.

The speed of compression and rebound of the rubber is critical for the sensor to be able to detect – and distinguish between – separate touches in quick succession.

The thin rubber film between the two electrodes stores electrical charges, much like a battery. When pressure is exerted on the sensor, the rubber film compresses, which changes the amount of electrical charges the film can store. That change is detected by the electrodes and is what enables the sensor to transmit what it is "feeling."

The largest sheet of sensors that Bao's group has produced to date measures about seven centimeters on a side. The sheet exhibited a great deal of flexibility, indicating it should perform well when wrapped around a surface mimicking the curvature of something such as a human hand or the sharp angles of a robotic arm.

Bao said that molding the rubber in different shapes yields sensors that are responsive to different ranges of pressure. "It's the same as for human skin, which has a whole range of sensitivities," she said. "Fingertips are the most sensitive, while the elbow is quite insensitive."

The sensors have from several hundred thousand up to 25 million pyramids per square centimeter. Under magnification, the array of tiny structures looks like the product of an ancient Egyptian micro-civilization obsessed with order and gone mad with productivity.

But that density allows the sensors to perceive pressures "in the range of a very, very gentle touch," Bao said. By altering the configuration of the microstructure or the density of the sensors, she thinks the sensor can be refined to detect subtleties in the shape of an object.

"If we can make this in higher resolution, then potentially we should be able to have the image on a coin read by the sensor," she said. A robotic hand covered with the electronic skin could feel a surface and know rough from smooth.

That degree of sensitivity could make the sensors useful in a broad range of medical applications, including robotic surgery, Bao said. In addition, using bandages equipped with the sensors could aid in healing of wounds and incisions. Doctors could use data from the sensors to be sure the bandages were not too tight.

Automobile safety could also be enhanced. "If a driver is tired, or drunk, or falls asleep at the wheel, their hands might loosen or fall off the wheel," said Benjamin Tee, graduate student in electrical engineering and a coauthor. "If there are pressure sensors that can sense that no hands are holding the steering wheel, the car could be equipped with some automatic safety device that could sound an alarm or kick in to slow the car down. This could be simpler and cost less than other methods of detecting driver fatigue."

The team also invented a new type of transistor in which they used the structured, flexible rubber film to replace a component that is normally rigid in a typical transistor. When pressure is applied to their new transistor, the pressure causes a change in the amount of current that the transistor puts out. The new, flexible transistors could also be used in making artificial skin, Bao said.

As Bao's team continues its research, the members may find applications not yet considered as well as other ways to demonstrate the sensitivity of their sensors. They have already expanded their stable of insects beyond the bluebottle fly to include some beautiful, delicate looking – albeit slightly heavier – butterflies.

But if the researchers wanted an even more ethereal demonstration, could the sensors detect the bubbles rising in a glass of champagne?

"If the bubbles coming out from the champagne impinge onto the pressure sensor, that might be possible," Bao said. "That would be an interesting experiment to do in the lab."

INFORMATION:

New artificial skin could make prosthetic limbs and robots more sensitive

2010-09-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Would a molecular horse trot, pace or glide across a surface?

2010-09-13

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Molecular machines can be found everywhere in nature, for example, transporting proteins through cells and aiding metabolism. To develop artificial molecular machines, scientists need to understand the rules that govern mechanics at the molecular or nanometer scale (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter).

To address this challenge, a research team at the University of California, Riverside studied a class of molecular machines that 'walk' across a flat metal surface. They considered both bipedal machines that walk on two 'legs' and quadrupedal ones ...

New pathway identified in Parkinson's through brain imaging

2010-09-13

(NEW YORK, NY, September 13, 2010) – A new study led by researchers at Columbia University Medical Center has identified a novel molecular pathway underlying Parkinson's disease and points to existing drugs which may be able to slow progression of the disease.

The pathway involved proteins – known as polyamines – that were found to be responsible for the increase in build-up of other toxic proteins in neurons, which causes the neurons to malfunction and, eventually, die. Though high levels of polyamines have been found previously in patients with Parkinson's, the new ...

Wives as the new breadwinners

2010-09-13

Durham, NH—September 13, 2010— During the recent recession in the United States, many industries suffered significant layoffs, leaving individuals and families to revise their spending and rethink income opportunities. Many wives are increasingly becoming primary breadwinners or entering the labor market. A new article in Family Relations tests "the added worker" theory, which suggests wives who are not working may seek work as a substitute for husband's labor if he becomes unemployed, and finds that during a time of economic downturn wives are more likely to enter the ...

Making cookies that are good for your heart

2010-09-13

VIDEO:

Years of research has proven that saturated and trans fats clog arteries, make it tough for the heart to pump and are not valuable components of any diet. Unfortunately, they...

Click here for more information.

COLUMBIA, Mo. ¬— Years of research has proven that saturated and trans fats clog arteries, make it tough for the heart to pump and are not valuable components of any diet. Unfortunately, they are contained in many foods. Now, a University of Missouri research ...

Obama administration responds to call to action from Concordia researchers

2010-09-13

Montreal / September 13, 2010 – September 21, 2010 marks the one year anniversary of the release of a landmark document produced by researchers at Concordia University. Mobilizing The Will to Intervene (W2I) offers governments practical steps to prevent future genocides and mass atrocities. Produced by researchers with the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS) based at Concordia, the document was presented to the governments of Canada and The United States of America. It has already yielded concrete results.

Under President Barack Obama's leadership, ...

Latent HIV infection focus of NIDA's 2010 Avant-Garde Award

2010-09-13

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health, announced today that Dr. Eric M. Verdin of the J. David Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco, Calif., has been selected as the 2010 recipient of the NIDA Avant-Garde Award for HIV/AIDS Research for his proposal to study the mechanisms of latent HIV infection. NIDA's annual Avant-Garde award competition, now in its third year, is intended to stimulate high-impact research that may lead to groundbreaking opportunities for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS in drug abusers. Awardees ...

New study reconciles conflicting data on mental aging

2010-09-13

WASHINGTON — A new look at tests of mental aging reveals a good news-bad news situation. The bad news is all mental abilities appear to decline with age, to varying degrees. The good news is the drops are not as steep as some research showed, according to a study published by the American Psychological Association.

"There is now convincing evidence that even vocabulary knowledge and what's called crystallized intelligence decline at older ages," said study author Timothy Salthouse, PhD.

Longitudinal test scores look good in part because repeat test-takers grow familiar ...

Scientists glimpse dance of skeletons inside neurons

2010-09-13

Scientists at Emory University School of Medicine have uncovered how a structural component inside neurons performs two coordinated dance moves when the connections between neurons are strengthened.

The results are published online in the journal Nature Neuroscience, and will appear in a future print issue.

In experiments with neurons in culture, the researchers can distinguish two separate steps during long-term potentiation, an enhancement of communication between neurons thought to lie behind learning and memory. Both steps involve the remodeling of the internal ...

CU-Boulder study sheds light on how our brains get tripped up when we're anxious

2010-09-13

A new University of Colorado at Boulder study sheds light on the brain mechanisms that allow us to make choices and ultimately could be helpful in improving treatments for the millions of people who suffer from the effects of anxiety disorders.

In the study, CU-Boulder psychology Professor Yuko Munakata and her research colleagues found that "neural inhibition," a process that occurs when one nerve cell suppresses activity in another, is a critical aspect in our ability to make choices.

"The breakthrough here is that this helps us clarify the question of what is happening ...

Energy Express focus issue: Thin-film photovoltaic materials and devices

2010-09-13

WASHINGTON, September 13 – Developing renewable energy sources has never been more important, and solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies show great potential in this field. They convert direct sunlight into electricity with little impact on the environment. This field is constantly advancing, developing technologies that can convert power more efficiently and at a lower cost. To highlight breakthroughs in this area, the editors of Energy Express, a bi-monthly supplement to Optics Express, the open-access journal of the Optical Society (OSA), today published a special Focus ...