(Press-News.org) Accurate, safe prescribing information for children is often unavailable to doctors in Canada because pharmaceutical companies will not disclose information to Health Canada, states an editorial in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) (pre-embargo link only) http://www.cmaj.ca/embargo/cmaj110563.pdf

Health professionals in Canada as well as other countries such as Japan and Australia, unlike their colleagues in the United States and Europe, do not have access to the same body of evidence regarding pediatric dosing.

"As a consequence, Canadian children and youth may fall victim to medication errors and mistreatment simply because of limited access to information about pediatric drugs," writes Dr. Paul Hébert, Editor-in-Chief, CMAJ, with coauthors.

Many drugs in the US that have specific pediatric labeling are described in Canada as having "insufficient evidence."

"Children are not little adults," state the authors. "Pediatric labelling should go well beyond simply adjusting adult doses to a pediatric weight, because this is inappropriate and potentially dangerous."

They cite as an example the increased suicide risk from early off-label prescribing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors guided only by data in adults.

While the pharmaceutical industry maintains that pediatric markets are small and not profitable, the US and Europe have introduced financial incentives to encourage research in children. The US Pediatric Research Equity Act requires drug companies to conduct studies and submit results to the US Food and Drug Administration for drugs they expect will be used in children.

"In line with recommendations of the World Health Organization, we need international harmonization of laws to ensure that appropriate incentives are in place to promote pediatric research necessary for pediatric indications and prescribing information," write the authors.

They conclude with a call to politicians to enact strict legislation similar to that in the US to protect Canadian children.

### END

Safe prescribing information for children in Canada often hard to find

2011-06-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Glowing Cornell dots -- a potential cancer diagnostic tool set for human trials

2011-06-14

NEW YORK – The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first clinical trial in humans of a new technology: Cornell Dots, brightly glowing nanoparticles that can light up cancer cells in PET-optical imaging.

A paper describing this new medical technology, "Multimodal silica nanoparticles are effective cancer-targeted probes in a model of human melanoma," will be published June 13, 2011 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation (July 2011). This is a collaboration between Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), Cornell University, and Hybrid Silica ...

More genetic diseases linked to potentially fixable gene-splicing problems

2011-06-14

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A new Brown University computer analysis that predicts the effect of genetic mutations on how the body splices mRNA indicates as many as a third of disease-related mutations may be linked to splicing problems — more than double the proportion previously thought.

"Something like 85 percent of the mutations in the Human Gene Mutation Database are presumed to affect how proteins are coded, but what this work shows is that 22 percent of those are affecting the splicing process," said William Fairbrother, assistant professor of biology ...

Decoding chronic lymphocytic leukemia

2011-06-14

A paper published online on June 13 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (www.jem.org) identifies new gene mutations in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)—a disease often associated with lack of response to chemotherapy and poor overall survival.

CLL is the most common leukemia in the Western world, but the disease varies greatly from patient to patient with regard to prognosis, survival, and disease course. In attempt to understand the genetic basis for this heterogeneity, a group led by Riccardo Dalla-Favera at Columbia University and Gianluca Gaidano ...

NIH researchers find new clues about aging

2011-06-14

National Institutes of Health researchers have identified a new pathway that sets the clock for programmed aging in normal cells. The study provides insights about the interaction between a toxic protein called progerin and telomeres, which cap the ends of chromosomes like aglets, the plastic tips that bind the ends of shoelaces.

The study by researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) appears in the June 13, 2011 early online edition of the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Telomeres wear away during cell division. When they degrade sufficiently, ...

Sniffing out a new source of stem cells

2011-06-14

A team of researchers, led by Emmanuel Nivet, now at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, has generated data in mice that suggest that adult stem cells from immune system tissue in the smell-sensing region of the human nose (human olfactory ecto–mesenchymal stem cells [OE-MSCs]) could provide a source of cells to treat brain disorders in which nerve cells are lost or irreparably damaged.

Stem cells are considered by many to be promising candidate sources of cells for the regeneration and repair of tissues damaged by various brain disorders (including traumatic ...

JCI online early table of contents: June 13, 2011

2011-06-14

EDITOR'S PICK: Sniffing out a new source of stem cells

A team of researchers, led by Emmanuel Nivet, now at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, has generated data in mice that suggest that adult stem cells from immune system tissue in the smell-sensing region of the human nose (human olfactory ecto–mesenchymal stem cells [OE-MSCs]) could provide a source of cells to treat brain disorders in which nerve cells are lost or irreparably damaged.

Stem cells are considered by many to be promising candidate sources of cells for the regeneration and repair ...

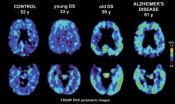

Brain scan identifies patterns of plaques and tangles in adults with Down syndrome

2011-06-14

In one of the first studies of its kind, UCLA researchers used a unique brain scan to assess the levels of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles — the hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease — in adults with Down syndrome.

Published in the June edition of the Archives of Neurology, the finding may offer an additional clinical tool to help diagnose dementia in adults with Down syndrome, a genetic disorder caused by the presence of a complete or partial extra copy of chromosome 21.

Adults with this disorder develop Alzheimer's-like plaque and tangle deposits early, ...

Chillingham cattle cowed by climate change

2011-06-14

Spring flowers are opening sooner and songbirds breeding earlier in the year, but scientists know little about how climate change is affecting phenology – the timing of key biological events – in UK mammals. Now, a new study on Northumberland's iconic Chillingham cattle published in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Animal Ecology shows climate change is altering when these animals breed, and fewer calves are surviving as a result.

The team of ecologists lead by Dr Sarah Burthe of the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology were able to use the cattle to discover more ...

Pacemaker implantation for heart failure does not benefit nearly half of the patients

2011-06-14

A new meta-analysis study, led by physician researchers at University Hospitals (UH) Case Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, and to be published in the Archives of Internal Medicine (embargoed until June 13, 4 p.m. EDT), shows that three-lead cardiac pacemakers implanted in those with heart failure fail to help up to 40 percent of patients with such devices.

"These findings have significant clinical implications and impact tens of thousands of patients in the U.S.," said Ilke Sipahi, MD, Associate Director of Heart Failure and Transplantation ...

Genetic factor controls health-harming inflammation in obese

2011-06-14

CLEVELAND – June 13, 2011 –Researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine have discovered a genetic factor that can regulate obesity-induced inflammation that contributes to chronic health problems.

If they learn to control levels of the factor in defense cells called macrophages, "We have a shot at a novel treatment for obesity and its complications, such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer," said Mukesh K. Jain, MD, Ellery Sedgwick Jr. Chair, director of the Case Cardiovascular Research Institute, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University ...