(Press-News.org) Were dinosaurs slow and lumbering, or quick and agile?

It depends largely on whether they were cold- or warm-blooded.

When dinosaurs were first discovered in the mid-19th century, paleontologists thought they were plodding beasts that relied on their environment to keep warm, like modern-day reptiles.

But research during the last few decades suggests that they were faster creatures, nimble like the velociraptors or T. rex depicted in the movie Jurassic Park, requiring warmer, regulated body temperatures.

Now, researchers, led by Robert Eagle of the California Institute of Technology, have developed a new way of determining the body temperatures of dinosaurs for the first time, providing new insights into whether dinosaurs were cold- or warm-blooded.

"Eagle and colleagues have applied the newest and most innovative techniques to answering the question of whether dinosaurs were warm- or cold-blooded," says Lisa Boush, program director in the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Earth Sciences, which funded the research.

"The team has made important strides in discovering that the body temperature of dinosaurs was close to that of mammals, and that the dinosaurs' physiology allowed them to regulate that temperature. The result has implications for our understanding of dinosaurs' ecology--and demise."

By analyzing the teeth of sauropods--long-tailed, long-necked dinosaurs that were the biggest land animals ever to have lived--the scientists found that these dinosaurs were about as warm as most modern mammals.

"This is like being able to stick a thermometer in an animal that has been extinct for 150 million years," says Eagle, a geochemist at Caltech and lead author of a paper to be published online today in the journal Science Express.

"The consensus was that no one would ever measure dinosaur body temperatures, that it's impossible to do," says John Eiler, a co-author and geochemist at Caltech. But using a technique pioneered in Eiler's lab, the team did just that.

The researchers analyzed 11 teeth, unearthed up in Tanzania, Wyoming and Oklahoma, that belonged to the dinosaurs Brachiosaurus and Camarasaurus.

They found that Brachiosaurus had a temperature of about 38.2 degrees Celsius (100.8 degrees Fahrenheit) and Camarasaurus had one of about 35.7 degrees Celsius (96.3 degrees Fahrenheit), warmer than modern and extinct crocodiles and alligators, but cooler than birds.

The measurements are accurate to within one or two degrees Celsius.

"Nobody has used this approach to look at dinosaur body temperatures before, so our study provides a completely different angle on the long-standing debate about dinosaur physiology," Eagle says.

The fact that the temperatures were similar to those of most modern mammals might seem to imply that dinosaurs had a warm-blooded metabolism.

But, the researchers say, the issue is more complex. Because sauropod dinosaurs were so huge, they could retain their body heat much more efficiently than smaller mammals like humans.

"The body temperatures we've estimated provide key information that any model of dinosaur physiology has to be able to explain," says Aradhna Tripati, a co-author who's a geochemist at University of California, Los Angeles and visiting geochemist at Caltech. "As a result, the data can help scientists test physiological models to explain how these organisms lived."

The measured temperatures are lower than what's predicted by some models of dinosaur body temperatures, suggesting there is something missing in scientists' understanding of dinosaur physiology.

These models imply that dinosaurs were so-called gigantotherms, that they maintained warm temperatures by their sheer size.

To explain the lower temperatures, the researchers suggest that dinosaurs could have had physiological or behavioral adaptations that allowed them to avoid getting too hot.

The dinosaurs could have had lower metabolic rates to reduce the amount of internal heat. They could also have had something like an air-sac system to dissipate heat.

Alternatively, they could have dispelled heat through their long necks and tails.

Previously, researchers have only been able to use indirect ways to gauge dinosaur metabolism or body temperatures.

For example, they inferred dinosaur behavior and physiology by figuring out how fast dinosaurs ran based on the spacing of dinosaur tracks, studying the ratio of predators to prey in the fossil record, or measuring the growth rates of bone.

But these lines of evidence were often in conflict.

"For any position you take, you can easily find counter-examples," Eiler says. "How an organism budgets the energy supply it gets from food, and creates and stores the energy in its muscles--there are no fossil remains for that."

Eagle, Eiler and colleagues developed what's known as a clumped-isotope technique that shows that it's possible to determine accurate body temperatures of dinosaurs.

"We're getting at body temperature through a line of reasoning that I think is relatively bullet-proof, provided you can find well-preserved samples," Eiler says.

In this method, the researchers measured the concentrations of the rare isotopes carbon-13 and oxygen-18 in bioapatite, a mineral found in teeth and bone.

How often these isotopes bond with each other--or "clump"--depends on temperature.

The lower the temperature, the more carbon-13 and oxygen-18 bond in bioapatite. Measuring the clumping of these isotopes is a direct way to determine the temperature of the environment in which the mineral formed--in this case, inside the dinosaur.

"What we're doing is special in that it's thermodynamically-based," Eiler says. "Thermodynamics, like the laws of gravity, is independent of setting, time and context."

Because thermodynamics worked the same way 150 million years ago as it does today, measuring isotope clumping is a reliable technique, says Eiler.

Identifying the most well-preserved samples of dinosaur teeth was one of the major challenges of the analysis.

The scientists used several ways of finding the best samples. For example, they compared the isotopic compositions of resistant parts of teeth--the enamel--with easily altered materials like the fossil bones of related animals.

The next step, the researchers say, is to determine the temperatures of more dinosaur samples, and extend the study to other species of extinct vertebrates.

In particular, discovering the temperatures of unusually small and young dinosaurs would help test whether dinosaurs were indeed gigantotherms.

Knowing the body temperatures of more dinosaurs and other extinct animals would also allow scientists to learn more about how the physiology of modern mammals and birds evolved.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Eagle, Eiler and Tripati, co-authors of the paper are Thomas Tütken from the University of Bonn, Germany; Caltech undergraduate Taylor Martin; Henry Fricke from Colorado College; Melissa Connely from the Tate Geological Museum in Casper, Wyoming; and Richard Cifelli from the University of Oklahoma. Eagle also has a research affiliation with UCLA.

The research was also supported by the German Research Foundation.

Scientists measure body temperature of dinosaurs for the first time

Some dinosaurs were as warm as modern mammals

2011-06-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New procedure treats atrial fibrillation

2011-06-28

Doctors at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are performing a new procedure to treat atrial fibrillation, a common irregular heartbeat.

Available at only a handful of U.S. medical centers, this "hybrid" procedure combines minimally invasive surgical techniques with the latest advances in catheter ablation, a technique that applies scars to the heart's inner surface to block signals causing the heart to misfire. The two-pronged approach gives doctors access to both the inside and outside of the heart at the same time, helping to more completely block ...

Analyzing agroforestry management

2011-06-28

MADISON, WI, JUNE 28, 2011 -- The evaluation of both nutrient and non-nutrient resource interactions provides information needed to sustainably manage agroforestry systems. Improved diagnosis of appropriate nutrient usage will help increase yields and also reduce financial and environmental costs. To achieve this, a management support system that allows for site-specific evaluation of nutrient-production imbalances is needed.

Scientists at the University of Toronto and the University of Saskatchewan have developed a conceptual framework to diagnosis nutrient and non-nutrient ...

Neuroscientists find famous optical illusion surprisingly potent

2011-06-28

VIDEO:

Scientists have figured out the brain mechanism that makes this optical illusion work. The illusion, known as "motion aftereffect " in scientific circles, causes us to see movement where none exist

Click here for more information.

Scientists have come up with new insight into the brain processes that cause the following optical illusion:

Focus your eyes directly on the "X" in the center of the image in this short video (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BXnUckHbPqM&feature=player_embedded)

The ...

Insight into plant behavior could aid quest for efficient biofuels

2011-06-28

Tiny seawater algae could hold the key to crops as a source of fuel and plants that can adapt to changing climates.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have found that the tiny organism has developed coping mechanisms for when its main food source is in short supply.

Understanding these processes will help scientists develop crops that can survive when nutrients are scarce and to grow high-yield plants for use as biofuels.

The alga normally feeds by ingesting nitrogen from surrounding seawater but, when levels are low, it reduces its intake and instead absorbs ...

Serum-free cultures help transplanted MSCs improve efficacy

2011-06-28

Tampa, Fla. (June 28, 2011) – Mensenchymal stem cells (MSCs), multipotent cells identified in bone marrow and other tissues, have been shown to be therapeutically effective in the immunosuppression of T-cells, the regeneration of blood vessels, assisting in skin wound healing, and suppressing chronic airway inflammation in some asthma cases. Typically, when MSCs are being prepared for therapeutic applications, they are cultured in fetal bovine serum.

A study conducted by a research team from Singapore and published in the current issue of Cell Medicine [2(1)], freely ...

JetBoarder International Launches The 'Sprint', The Worlds First Kids' JetBoarder

2011-06-28

In another world first, Australian Company JetBoarder pioneers the way in the new sport of JetBoarding. Their newest model, which previewed at Sanctuary Cove International Boat Show in Australia, is a real world first.

Click link to see more: http://vimeo.com/24210179

Called the 'Sprint', the focus with the kids' JetBoarder was safety first and fun second, in a new experience for kids aged 12-16. Our SPRINT Model achieves this plus more advises Chris Kanyaro. "We want to give kids the opportunity to enjoy the latest craze taking the world by storm" in ...

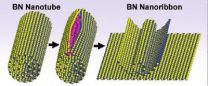

Splitsville for boron nitride nanotubes

2011-06-28

For Hollywood celebrities, the term "splitsville" usually means "check your prenup." For scientists wanting to mass-produce high quality nanoribbons from boron nitride nanotubes, "splitsville" could mean "happily ever after."

Scientists with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley, working with scientists at Rice University, have developed a technique in which boron nitride nanotubes are stuffed with atoms of potassium until the tubes split open along a longitudinal seam. This creates defect-free boron nitride ...

Chemical produced in pancreas prevented and reversed diabetes in mice

2011-06-28

TORONTO, Ont., June 28, 2011—A chemical produced by the same cells that make insulin in the pancreas prevented and even reversed Type 1 diabetes in mice, researchers at St. Michael's Hospital have found.

Type 1 diabetes, formerly known as juvenile diabetes, is characterized by the immune system's destruction of the beta cells in the pancreas that make and secrete insulin. As a result, the body makes little or no insulin.

The only conventional treatment for Type 1 diabetes is insulin injection, but insulin is not a cure as it does not prevent or reverse the loss of ...

Can soda tax curb obesity?

2011-06-28

EVANSTON, Ill. --- To many, a tax on soda is a no-brainer in advancing the nation's war on obesity. Advocates point to a number of studies in recent years that conclude that sugary drinks have a lot to do with why Americans are getting fatter.

But obese people tend to drink diet sodas, and therefore taxing soft drinks with added sugar or other sweeteners is not a good weapon in combating obesity, according to a new Northwestern University study.

An amendment to Illinois Senate Bill 396 would add a penny an ounce to the cost of most soft drinks with added sugar or sweeteners, ...

Inkjet printing could change the face of solar energy industry

2011-06-28

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Inkjet printers, a low-cost technology that in recent decades has revolutionized home and small office printing, may soon offer similar benefits for the future of solar energy.

Engineers at Oregon State University have discovered a way for the first time to create successful "CIGS" solar devices with inkjet printing, in work that reduces raw material waste by 90 percent and will significantly lower the cost of producing solar energy cells with some very promising compounds.

High performing, rapidly produced, ultra-low cost, thin film solar electronics ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

[Press-News.org] Scientists measure body temperature of dinosaurs for the first timeSome dinosaurs were as warm as modern mammals