(Press-News.org) Researchers have probed deeper into human evolution by developing an elegant new technique to analyse whole genomes from different populations. One key finding from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute's study is that African and non-African populations continued to exchange genetic material well after migration out-of-Africa 60,000 years ago. This shows that interbreeding between these groups continued long after the original exodus.

For the first time genomic archaeologists are able to infer population size and history

using single genomes, a technique that makes fewer assumptions than existing methods, allowing for more detailed insights. It provides a fresh view of the history of mankind from 10,000 to one million years ago.

"Using this algorithm, we were able to provide new insights into our human history," says Dr Richard Durbin, joint head of Human Genetics and leader of the Genome Informatics Group at the Sanger Institute. "First, we see an apparent increase in effective human population numbers around the time that modern humans arose in Africa over 100,000 years ago.

"Second, when we look at non-African individuals from Europe and East Asia, we see

a shared history of a dramatic reduction in population, or bottleneck, starting about 60,000 years ago, as others have also observed. But unlike previous studies we also see evidence for continuing genetic exchange with African populations for tens of thousands of years after the initial out-of-Africa bottleneck until 20,000 to 40,000 years ago.

"Previous methods to explore these questions using genetic data have looked at a subset of the human genome. Our new approach uses the whole sequence of single individuals, and relies on fewer assumptions. Using such techniques we will be able to capitalize on the revolution in genome sequencing and analysis from projects such as The 1000 Genomes Project, and, as more people are sequenced, build a progressively finer detail picture of human genetic history."

The team sequenced and compared four male genomes: one each from China, Europe, Korea and West Africa respectively. The researchers found that, although the African and non-African populations might have started to differentiate as early as 100,000 to 120,000 years ago, they largely remained as one population until approximately 60,000 to 80,000 years ago.

Following this the European and East Asian ancestors went through a period where their effective population size crashed to approximately one-tenth of its earlier size, overlapping the period when modern human fossils and artefacts start to appear across Europe and Asia. But, for at least the first 20,000 years of this period, it appears that the out-of-Africa and African populations were not genetically separated. A possible explanation could be that new emigrants from Africa continued to join the out-of-Africa populations long after the original exodus.

"This elegant tool provides opportunities for further research to enable us to learn more about population history," says co-author Heng Li, from the Sanger Institute. "Each human genome contains information from the mother and the father, and the differences between these at any place in the genome carry information about its history. Since the genome sequence is so large, we can combine the information from tens of thousands of different places in the genome to build up a composite history of the ancestral contributions to the particular individual who was sequenced.

"We can also get at the historical relationship between two different ancestral populations by comparing the X chromosomes from two males. This works because men only have one copy of the X chromosome each, so we can combine the X chromosomes of two men and treat them in the same way as the rest of the genome for one person, with the results telling us about the way in which the ancestral populations of the two men separated.

"The novel statistical method we developed is computationally efficient and doesn't make restrictive assumptions about the way that population size changed. Although not inconsistent with previous results, these findings allow new types of historical events to be explored, leading to new observations about the history of mankind."

The researchers believe that this technique can be developed further to enable even more fine-grained discoveries by sequencing multiple genomes from different populations. In addition, beyond human history, there is also the potential to investigate the population size history of other species for which a single genome sequence has been obtained.

###

Notes to Editors

Publication Details

Inference of human population history from individual whole genome sequences.

Li H, Durbin R.

Nature 2011.

DOI: 10.1038/nature10231

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

http://www.sanger.ac.uk

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.

http://www.wellcome.ac.uk

END

A cancer cell may seem out of control, growing wildly and breaking all the rules of orderly cell life and death. But amid the seeming chaos there is a balance between a cancer cell's revved-up metabolism and skyrocketing levels of cellular stress. Just as a cancer cell depends on a hyperactive metabolism to fuel its rapid growth, it also depends on anti-oxidative enzymes to quench potentially toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by such high metabolic demand.

Scientists at the Broad Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have discovered a novel compound ...

Contact: Christina DeAngelis

christina.deangelis@case.edu

216-368-3635

Kevin Mayhood

kevin.mayhood@case.edu

216-368-5004

Case Western Reserve University

Case Western Reserve restores breathing after spinal cord injury in rodent model

Study published in the online issue of Nature on July 14

CLEVELAND – July 13, 2011 –Researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine bridged a spinal cord injury and biologically regenerated lost nerve connections to the diaphragm, restoring breathing in an adult rodent model of spinal cord injury. The work, which ...

STANFORD, Calif. — The addition of two particular gene snippets to a skin cell's usual genetic material is enough to turn that cell into a fully functional neuron, report researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine. The finding, to be published online July 13 in Nature, is one of just a few recent reports of ways to create human neurons in a lab dish.

The new capability to essentially grow neurons from scratch is a big step for neuroscience research, which has been stymied by the lack of human neurons for study. Unlike skin cells or blood cells, neurons ...

PHILADELPHIA - Targeted therapies that are designed to suppress the formation of new blood vessels in tumors, such as Avastin (bevacizumab), have slowed cancer growth in some patients. However, they have not produced the dramatic responses researchers initially thought they might. Now, research from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania might help to explain the modest responses. The discovery, published in the July 14 issue of Nature, suggests novel treatment combinations that could boost the power of therapies based on slowing blood vessel ...

A new study by investigators from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine has confirmed the existence of a "trial effect" in clinical trials for treatment of HIV.

Trial effect is an umbrella term for the benefit experienced by study participants simply by virtue of their participating in the trial. It includes the benefit of newer and more effective treatments, the way those treatments are delivered, increased care and follow-up, and the patient's own behavior change as a result of being under observation.

"Trial effect is notoriously difficult ...

Changing from running payroll by hand to computerized payroll can be quick and painless. Small business-focused payroll software developer Halfpricesoft.com announced the launch of new improved ezPaycheck payroll software and small business owners can get a free, 30-day trial by downloading ezPaycheck software from http://www.halfpricesoft.com/payroll_software_download.asp.

This trial version contains all of the features and functions of the full version, except tax form printing, allowing customers to thoroughly test drive the product. Once customers are satisfied that ...

Tiny chemical particles emitted by diesel exhaust fumes could raise the risk of heart attacks, research has shown.

Scientists have found that ultrafine particles produced when diesel burns are harmful to blood vessels and can increase the chances of blood clots forming in arteries, leading to a heart attack or stroke.

The research by the University of Edinburgh measured the impact of diesel exhaust fumes on healthy volunteers at levels that would be found in heavily polluted cities.

Scientists compared how people reacted to the gases found in diesel fumes – such as ...

(Chicago, July 13, 2011)– How influential are mass media portrayals of chimpanzees in television, movies, advertisements and greeting cards on public perceptions of this endangered species? That is what researchers based at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo sought to uncover in a new nationwide study published today in in PLoS One, the open-access journal of the Public Library of Sciences. Their findings reveal the significant role that media plays in creating widespread misunderstandings about the conservation status and nature of this great ape.

A majority of study respondents ...

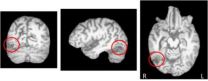

PITTSBURGH—Certain brain injuries can cause people to lose the ability to visually recognize objects — for example, confusing a harmonica for a cash register.

Neuroscientists from Carnegie Mellon University and Princeton University examined the brain of a person with object agnosia, a deficit in the ability to recognize objects that does not include damage to the eyes or a general loss in intelligence, and have uncovered the neural mechanisms of object recognition. The results, published by Cell Press in the July 15th issue of the journal Neuron, describe the functional ...

More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere causes soil to release the potent greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide, new research published in this week's edition of Nature reveals. "This feedback to our changing atmosphere means that nature is not as efficient in slowing global warming as we previously thought," said Dr Kees Jan van Groenigen, Research Fellow at the Botany department at the School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, and lead author of the study.

Van Groenigen, along with colleagues from Northern Arizona University and the University of Florida, ...