(Press-News.org) Thermal expansion of seawater contributed only slightly to rising sea levels compared to melting ice sheets during the Last Interglacial Period, a University of Arizona-led team of researchers has found.

The study combined paleoclimate records with computer simulations of atmosphere-ocean interactions and the team's co-authored paper is accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters.

As the world's climate becomes warmer due to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, sea levels are expected to rise by up to three feet by the end of this century.

But the question remains: How much of that will be due to ice sheets melting as opposed to the oceans' 332 million cubic miles of water increasing in volume as they warm up?

For the study, UA team members analyzed paleoceanic records of global distribution of sea surface temperatures of the warmest 5,000-year period during the Last Interglacial, a warm period that lasted from 130,000 to 120,000 years ago.

The researchers then compared the data to results of computer-based climate models simulating ocean temperatures during a 200-year snapshot as if taken 125,000 years ago and calculating the contributions from thermal expansion of sea water.

The team found that thermal expansion could have contributed no more than 40 centimeters – less than 1.5 feet – to the rising sea levels during that time, which exceeded today's level up to eight meters or 26 feet.

At the same time, the paleoclimate data revealed average ocean temperatures that were only about 0.7 degrees Celsius, or 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit, above those of today.

"This means that even small amounts of warming may have committed us to more ice sheet melting than we previously thought. The temperature during that time of high sea levels wasn't that much warmer than it is today," said Nicholas McKay, a doctoral student at the UA's department of geosciences and the paper's lead author.

McKay pointed out that even if ocean levels rose to similar heights as during the Last Interglacial, they would do so at a rate of up to three feet per century.

"Even though the oceans are absorbing a good deal of the total global warming, the atmosphere is warming faster than the oceans," McKay added. "Moreover, ocean warming is lagging behind the warming of the atmosphere. The melting of large polar ice sheets lags even farther behind."

"As a result, even if we stopped greenhouse gas emissions right now, the Earth would keep warming, the oceans would keep warming, the ice sheets would keep shrinking, and sea levels would keep rising for a long time," he explained.

They are absorbing most of that heat, but they lag behind. Especially the large ice sheets are not in equilibrium with global climate," McKay added. "

Jonathan Overpeck, co-director of the UA's Institute of the Environment and a professor with joint appointments in the department of geosciences and atmospheric sciences, said: "This study marks the strongest case yet made that humans – by warming the atmosphere and oceans – are pushing the Earth's climate toward the threshold where we will likely be committed to four to six or even more meters of sea level rise in coming centuries."

Overpeck, who is McKay's doctoral advisor and a co-author of the study, added: "Unless we dramatically curb global warming, we are in for centuries of sea level rise at a rate of up to three feet per century, with the bulk of the water coming from the melting of the great polar ice sheets – both the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets."

According to the authors, the new results imply that 4.1 to 5.8 meters, or 13.5 to 19 feet, of sea level rise during the Last Interglacial period was derived from the Antarctic Ice Sheet, "reemphasizing the concern that both the Antarctic and Greenland Ice Sheets may be more sensitive to warming temperatures than widely thought."

"The central question we asked was, 'What are the warmest 5,000 years we can find for all these records, and what was the corresponding sea level rise during that time?'" McKay said.

Evidence for elevated sea levels is scattered all around the globe, he added. On Barbados and the Bahamas, for example, notches cut by waves into the rock six or more meters above the present shoreline have been dated to being 125,000 years old.

"Based on previous studies, we know that the sea level during the Last Interglacial was up to 8.5 meters higher than today," McKay explained.

"We already knew that the vast majority came from the melting of the large ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, but how much could the expansion of seawater have added to that?"

Given that sea surface temperatures were about 0.7 degrees warmer than today, the team calculated that even if the warmer temperatures reached all the way down to 2,000 meters depth – more than 6,500 feet, which is highly unlikely – expansion would have accounted for no more than 40 centimeters, less than a foot and a half.

"That means almost all of the substantial sea level rise in the Last Interglacial must have come from the large ice sheets, with only a small contribution from melted mountain glaciers and small ice caps," McKay said.

According to co-author Bette Otto-Bliesner, senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo., getting the same estimate of the role ocean expansion played on sea level rise increases confidence in the data and the climate models.

"The models allow us to attribute changes we observe in the paleoclimate record to the physical mechanisms that caused those changes," Otto-Bliesner said. "This helps tremendously in being able to distinguish mere correlations from cause-and-effect relationships."

The authors cautioned that past evidence is not a prediction of the future, mostly because global temperatures during the Last Interglacial were driven by changes in the Earth's orbit around the sun. However, current global warming is driven by increasing greenhouse gas concentrations.

The seasonal differences between the northern and the southern hemispheres were more pronounced during the Last Interglacial than they will be in the future.

"We expect something quite different for the future because we're not changing things seasonally, we're warming the globe in all seasons," McKay said.

"The question is, when we think about warming on a global scale and contemplate letting the climate system change to a new warmer state, what would we expect for the ice sheets and sea levels based on the paleoclimate record? The Last Interglacial is the most recent time when sea levels were much higher and it's a time for which we have lots of data," McKay added.

"The message is that the last time glaciers and ice sheets melted, sea levels rose by more than eight meters. Much of the world's population lives relatively close to sea level. This is going to have huge impacts, especially on poor countries," he added.

"If you live a meter above sea level, it's irrelevant what causes the rise. Whether sea levels are rising for natural reasons or for anthropogenic reasons, you're still going to be under water sooner or later."

INFORMATION:

Reference:

McKay, N., J. T. Overpeck, and B. Otto-Bliesner (2011). The role of ocean thermal expansion in Last Interglacial sea level rise. Geophys. Res. Lett., doi:10.1029/2011GL048280, in press. A version of the accepted paper is available online at the Geophysical Research Letters site: http://www.agu.org/journals/gl/papersinpress.shtml

Rising oceans -- too late to turn the tide?

Melting ice sheets contributed much more to rising sea levels than thermal expansion of warming ocean waters during the Last Interglacial Period, a UA-led team of researchers has found

2011-07-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NYU Langone Medical Center's tip sheet to the 2011 Alzheimer's Association International Conference

2011-07-19

NEW YORK, July 16, 2011 – Experts from the Center of Excellence on Brain Aging at NYU Langone Medical Center will present new research at the 2011 Alzheimer's Association International Conference on Alzheimer's disease to be held in Paris, France from July 16 – 21. Of particular interest is the presentation about mild cognitive impairment in retired football players, with Stella Karantzoulis, PhD, and the selected "Hot Topics" presentation about a new experimental approach to targeting amyloid plaques, with Fernando Goni, PhD. Each presentation is embargoed as noted below.

The ...

Newer techniques are making cardiac CT safer for children

2011-07-19

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) has excellent image quality and diagnostic confidence for the entire spectrum of pediatric patients, with significant reduction of risk with recent technological advancements, according to a study to be presented at the Sixth Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) in Denver, July 14-17.

"Traditionally, pediatric patients who require coronary artery imaging have undergone a cardiac catheterization, which is an invasive procedure with a significant radiation dose, requiring sedation ...

NYU researchers develop compound to block signaling of cancer-causing protein

2011-07-19

Researchers at New York University's Department of Chemistry and NYU Langone Medical Center have developed a compound that blocks signaling from a protein implicated in many types of cancer. The compound is described in the latest issue of the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

The researchers examined signaling by receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). Abnormal RTK signaling is a major underlying cause of various developmental disorders and diseases, including many forms of cancer. RTK signaling pathway employs interactions between proteins Sos and Ras, and accounts for a broad ...

Researchers provide means of monitoring cellular interactions

2011-07-19

Boston, MA – Using nanotechnology to engineer sensors onto the surface of cells, researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) have developed a platform technology for monitoring single-cell interactions in real-time. This innovation addresses needs in both science and medicine by providing the ability to further understand complex cell biology, track transplanted cells, and develop effective therapeutics. These findings are published in the July 17 issue of Nature Nanotechnology.

"We can now monitor how individual cells talk to one another in real-time with unprecedented ...

What keeps the Earth cooking?

2011-07-19

What spreads the sea floors and moves the continents? What melts iron in the outer core and enables the Earth's magnetic field? Heat. Geologists have used temperature measurements from more than 20,000 boreholes around the world to estimate that some 44 terawatts (44 trillion watts) of heat continually flow from Earth's interior into space. Where does it come from?

Radioactive decay of uranium, thorium, and potassium in Earth's crust and mantle is a principal source, and in 2005 scientists in the KamLAND collaboration, based in Japan, first showed that there was a way ...

'Love your body' to lose weight

2011-07-19

Almost a quarter of men and women in England and over a third of adults in America are obese. Obesity increases the risk of diabetes and heart disease and can significantly shorten a person's life expectancy. New research published by BioMed Central's open access journal International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity shows that improving body image can enhance the effectiveness of weight loss programs based on diet and exercise.

Researchers from the Technical University of Lisbon and Bangor University enrolled overweight and obese women on a year-long ...

Genetic research confirms that non-Africans are part Neanderthal

2011-07-19

Some of the human X chromosome originates from Neanderthals and is found exclusively in people outside Africa, according to an international team of researchers led by Damian Labuda of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Montreal and the CHU Sainte-Justine Research Center. The research was published in the July issue of Molecular Biology and Evolution.

"This confirms recent findings suggesting that the two populations interbred," says Dr. Labuda. His team places the timing of such intimate contacts and/or family ties early on, probably at the crossroads ...

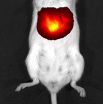

Newly developed fluorescent protein makes internal organs visible

2011-07-19

July 17, 2011 – (BRONX, NY) – Researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University have developed the first fluorescent protein that enables scientists to clearly "see" the internal organs of living animals without the need for a scalpel or imaging techniques that can have side effects or increase radiation exposure.

The new probe could prove to be a breakthrough in whole-body imaging – allowing doctors, for example, to noninvasively monitor the growth of tumors in order to assess the effectiveness of anti-cancer therapies. In contrast to other body-scanning ...

Heated AFM tip allows direct fabrication of ferroelectric nanostructures on plastic

2011-07-19

Using a technique known as thermochemical nanolithography (TCNL), researchers have developed a new way to fabricate nanometer-scale ferroelectric structures directly on flexible plastic substrates that would be unable to withstand the processing temperatures normally required to create such nanostructures.

The technique, which uses a heated atomic force microscope (AFM) tip to produce patterns, could facilitate high-density, low-cost production of complex ferroelectric structures for energy harvesting arrays, sensors and actuators in nano-electromechanical systems (NEMS) ...

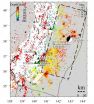

Study of soil effects from March 11 Japan earthquake could improve building design

2011-07-19

Japan's March 11 Tohoku Earthquake is among the strongest ever recorded, and because it struck one of the world's most heavily instrumented seismic zones, this natural disaster is providing scientists with a treasure trove of data on rare magnitude 9 earthquakes. Among the new information is what is believed to be the first study of how a shock this powerful affects the rock and soil beneath the surface.

Analyzing data from multiple measurement stations, scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology found that the quake weakened subsurface materials by as much as ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

Rice lab to help develop bioprinted kidneys as part of ARPA-H PRINT program award

Researchers discover ABCA1 protein’s role in releasing molecular brakes on solid tumor immunotherapy

[Press-News.org] Rising oceans -- too late to turn the tide?Melting ice sheets contributed much more to rising sea levels than thermal expansion of warming ocean waters during the Last Interglacial Period, a UA-led team of researchers has found