(Press-News.org) Melanoma is devastating on many fronts: rates are rising dramatically among young people, it is deadly if not caught early, and from a biological standpoint, the disease tends to adapt to even the most modern therapies, known as VEGF inhibitors. University of Rochester researchers, however, made an important discovery about proteins that underlie and stimulate the disease, opening the door for a more targeted treatment in the future.

This month in the journal Cancer Research, Lei Xu, Ph.D., assistant professor of Biomedical Genetics at the University of Rochester Medical Center, proposed that a receptor called GPR56 – which mostly has been studied in the context of brain formation -- has an important role in cancer progression.

Xu and colleagues believe they are the first to show the biological mechanisms of how GPR56 relates to the growth and spread of melanoma, and might even be responsible for triggering one of the lethal processes of cancer progression, known as angiogenesis.

"We are very excited about this work because not only did we find an important new factor in melanoma, but we have also shown the signaling pathways through which these G-protein coupled receptors could impede cancer cell growth," Xu said. "Perturbing these pathways could potentially lead to more effective treatments for malignant melanoma."

Melanoma killed an estimated 8,700 people in the United States in 2010, and in the last 25 years the incidence has been increasing to the point that it is now the most common form of cancer in young adults 25 to 29, and the second most common cancer among people in their teens and early 20s.

If diagnosed at an early stage the survival rate is 99 percent; however, the survival rate falls to 15 percent for people with advanced melanoma. One of the challenges is relapse. Even when melanoma is successfully controlled for a significant period of time, the disease can recur and act more aggressively than at the initial diagnosis.

The reason for this, according to Xu, is that we do not yet have a single drug therapy or a combination of therapies that reach the source of the problem.

To better understand the source, researchers looked to VEGF, or vascular endothelial growth factor, which plays a key role along the complex chain of interactions that occur as cancer develops and spreads. Most importantly, VEGF provides a potent chemical signal that stimulates new blood vessels. Tumor cells have a distinct need for oxygen and nutrients, and in this environment the nutrients in tumor cells trigger the secretion of the VEGF protein, which then leads to the formation of new blood vessels to fuel the tumor.

The dangerous cycle that feeds cancer cells with nutrients is referred to as angiogenesis. The Food and Drug Administration in recent years has approved several promising cancer drugs, called anti-angiogenesis therapies or VEGF inhibitors, which are designed to block the activity of VEGF protein once it has been secreted and released by the cells. Frequently, though, despite continuous therapy with anti-angiogenesis medications, some of the VEGF escapes, creating an environment for a relapse.

Xu's team wondered if the VEGF could be blocked earlier, before it was produced. Collaborators included post-doctoral fellow Liquan Yang, Ph.D., technical associate Sonali Mohanty, Arshad Rahman, Ph.D., associate professor of Pediatrics, Environmental Medicine, and Pharmacology and Physiology at URMC; and Glynis A. Scott, M.D., professor of Dermatology and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at URMC.

Knowing that some involvement with cancer cells had been reported in the literature, they began a detailed investigation of G-protein-couple receptors (GPCRs). In the context of other diseases GPCRs constitute 40 percent of drug targets, making it an attractive option to control cancer if a link could be established.

Using a mouse model and four different human melanoma cell lines, researchers explored the mechanics of how GPCRs regulate VEGF and the signaling pathways involved. Xu's team observed an opposing relationship between two key fragments of GPR56 (GPRN and GPRC) that played distinct roles in regulating VEGF in melanoma progression.

As a result, Xu believes that if this relationship between GPR56 fragments is exploited properly, VEGF production in melanoma cells could be shut down at its source.

Although the GPR56 molecule is not a drug target at the moment, Xu said, "we hope our paper creates more interest." The next step is to confirm the laboratory findings with melanoma cells freshly isolated from human patients.

###

Funding was provided by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award, the National Institutes of Health, and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to Richard O. Hynes, co-author and Xu's mentor. Hynes is the Daniel K. Ludwig Professor of Cancer Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

END

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — July 20, 2011 — A new drug targeting the PI3K gene in patients with advanced breast cancer shows promising results in an early phase I investigational study conducted at Virginia G. Piper Cancer at Scottsdale Healthcare, according to a presentation by oncologist Dr. Daniel D. Von Hoff at the 47th annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The drug under investigation, GDC-0941, manufactured by Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, Calif., targets the PI3K gene, which is abnormal in about 20-30 percent of patients with advanced ...

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University have developed a computer modeling method to accurately predict how a peripheral nerve axon responds to electrical stimuli, slashing the complex work from an inhibitory weeks-long process to just a few seconds.

The method, which enables efficient evaluation of a nerve's response to millions of electrode designs, is an integral step toward building more accurate and capable electrodes to stimulate nerves and thereby enable people with paralysis or amputated limbs better control of movement.

To increase the accuracy of the ...

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (July 20, 2011) – University of Minnesota Medical School and College of Biological Sciences researchers have made a key discovery showing that male sex must be maintained throughout life.

The research team, led by Drs. David Zarkower and Vivian Bardwell of the U of M Department of Genetics, Cell Biology and Development, found that removing an important male development gene, called Dmrt1, causes male cells in mouse testis to become female cells.

The findings are published online today in Nature.

In mammals, sex chromosomes (XX in female, XY ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- A University at Buffalo-led research team has developed a mathematical framework that could one day form the basis of technologies that turn road vibrations, airport runway noise and other "junk" energy into useful power.

The concept all begins with a granular system comprising a chain of equal-sized particles -- spheres, for instance -- that touch one another.

In a paper in Physical Review E this June, UB theoretical physicist Surajit Sen and colleagues describe how altering the shape of grain-to-grain contact areas between the particles dramatically ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Instead of calming fears, the death of Osama bin Laden actually led more Americans to feel threatened by Muslims living in the United States, according to a new nationwide survey.

In the weeks following the U.S. military campaign that killed bin Laden, the head of the terrorist organization Al Qaeda, American attitudes toward Muslim Americans took a significant negative shift, results showed.

Americans found Muslims living in the United States more threatening after bin Laden's death, positive perceptions of Muslims plummeted, and those surveyed were ...

DURHAM, N.C. – Esses are everywhere.

From economic trends, population growth, the spread of cancer, or the adoption of new technology, certain patterns inevitably seem to emerge. A new technology, for example, begins with slow acceptance, followed by explosive growth, only to level off before "hitting the wall."

When plotted on graph, this pattern of growth takes the shape of an "S."

While this S-curve has long been recognized by economists and scientists, a Duke University professor believes that a theory he developed explains the reason for the prevalence of this ...

Los Angeles, (July 2011) — Despite helping to push Hosni Mubarak and his regime from power, Egypt's liberals and pro-democracy activists are having trouble moving from revolution to politics, according to a recent article in the World Policy Journal (published by SAGE).

In this in-depth look at the Egyptian political landscape, the article's author, Jenna Krasjeki, examines various groups vying for influence and public support in the run-up to elections this fall. One common characteristic that Krasjeski notes is the lack of organization in the groups of young, liberal ...

A simple cut to the skin unleashes a complex cascade of chemistry to stem the flow of blood. Now, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have used evolutionary clues to reveal how a key clotting protein assembles. The finding sheds new light on common bleeding disorders.

The long tube-shaped protein with a vital role in blood clotting is called von Willebrand Factor (VWF). Made in cells that form the inner lining of blood vessels, VWF circulates in the blood seeking out sites of injury. When it finds them, its helical tube unfurls to catch ...

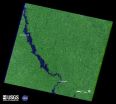

Flooding along the Missouri River continues as shown in recent Landsat satellite images of the Nebraska and Iowa border. Heavy rains and snowmelt have caused the river to remain above flood stage for an extended period.

A Landsat 5 image of the area from May 5, 2011 shows normal flow. In contrast, a Landsat 7 image from July 17 depicts flood conditions in the same location.

A national overview map of streamflow provided by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) WaterWatch graphically portrays the immense geographic extent of flooding in the Missouri River basin.

Monitoring ...

In the fight to improve global health, alleviate hunger, raise living standards and empower women in the developing world, chickens have an important role to play.

Jagdev Sharma, a researcher at the Center for Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology at Arizona State University's Biodesign Institute has been investigating the advantages of a more productive species of chicken for villagers in rural Uganda. He reports his findings this week at the American Veterinary Medical Association Meeting in Saint Louis, Missouri.

The star of this developing story is a type of chicken ...