(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY, (September 1, 2011) – Although several genes have been linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), it is still unknown how they cause this progressive neurodegenerative disease. In a new study, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have demonstrated that two ALS-associated genes work in tandem to support the long-term survival of motor neurons. The findings were published in the September 1 online edition of the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"Any therapy based on this discovery is probably a long way off. Nonetheless, it's an important step toward piecing together the various factors that contribute to ALS," says lead author Brian McCabe, PhD, assistant professor of pathology & cell biology in the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain and a member of the Center for Motor Neuron Biology and Disease at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC).

ALS, also known as "Lou Gehrig's disease," is a progressive disease that affects motor neurons — specialized nerve cells in the spinal cord and brainstem essential for controlling muscle strength and movement. ALS typically begins after age 50, eventually affecting one's ability to move, speak, and breathe. Some 30,000 Americans suffer from ALS at any given time. About 90 percent have a sporadic, or noninherited, form of the disease. The cause of sporadic ALS is unknown but likely involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors. The remaining 10 percent have a familial form of ALS, which is caused by an inherited genetic mutation. There is no cure for ALS. Symptoms are managed with medication, physical and speech therapy, assistive devices, and nutritional support. Many people with ALS die of respiratory complications within two to three years of diagnosis.

In the current experiment, the researchers examined the roles of two recently discovered ALS genes, FUS/TLS and TDP-43. Both genes are involved in the processing of messenger RNAs, which carry the genetic codes to make particular proteins. "The two genes make proteins with similar form and function, which suggested to us that they could work together, and that disruptions of either gene would affect neuronal survival," says Dr. McCabe. A competing view was that mutations to these genes cause abnormalities in their respective proteins that are toxic to motor neurons independent of their normal functions.

To determine which model is correct, the researchers turned to the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), which has genes similar to FUS/TLS and TDP-43 and reproduces quickly, making it a good model for genetic studies of ALS. For the study, Dr. McCabe's team created a line of flies with mutant FUS/TLS; flies with mutant TDP-43 had already been developed by an Italian research group.

In the first part of the study, the researchers found that flies with mutant FUS/TLS have decreased adulthood viability, diminished locomotor speed, and reduced longevity, compared with normal flies. The mutant flies were rescued (returned to normal) by inserting normal human FUS/TLS into their genome. The mutant flies were not rescued with ALS mutant human FUS/TLS. "This means that the gene works similarly in flies and in humans," says Dr. McCabe.

Flies with mutant TDP-43 showed similar deficits in survival, locomotion, and longevity. This line of flies was rescued with insertion of normal human TDP-43.

To determine whether the two genes interact, the team attempted to cross-rescue FUS/TLS or TDP-43 mutants by forcing overexpression of the other gene. Overexpression of FUS/TLS rescued flies with TDP-43 mutations, while overexpression of TDP-43 did not rescue flies with FUS/TLS mutations. "This finding demonstrates that FUS/TLS acts together with, and downstream of, TDP-43 in a common genetic pathway in neurons."

Whether these findings can be translated into therapy remains to be seen. "But one could imagine that if you could develop a drug or gene therapy that could make FUS/TLS more active, it might help in patients who have TDP-43 mutations," says Dr. McCabe.

"Our results show that these two genes work together in a familial ALS model," Dr. McCabe adds. "How ALS genes cause disease, and whether other genes work together, are big questions. The hope is that if we can eventually understand how all ALS genes interact, we can figure out how to intervene."

Dr. McCabe's paper is titled, "The ALS-associated proteins FUS and TDP-43 function together to affect Drosophila locomotion and life span." The paper's first authors are Ji-Wu Wang and Jonathan R. Brent at CUMC. Their coauthors include Andrew Tomlinson and Neil A. Shneider, also at CUMC.

###

Columbia University Medical Center

Office of Communications

701 West 168th Street, HHSC 2-206

New York, NY 10032

www.cumc.columbia.edu/newsroom

EMBARGOED UNTIL: 12 NOON (EDT), THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2011

Media Contact: Karin Eskenazi, 212-342-0508, ket2116@columbia.edu

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The study was funded by P2ALS and the Motor Neuron Center.

The Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain at Columbia University Medical Center is a multidisciplinary group that has forged links between researchers and clinicians to uncover the causes of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and other age-related brain diseases and discover ways to prevent and cure these diseases. It has partnered with the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center at Columbia University Medical Center which was established by an endowment in 1977 to focus on diseases of the nervous system. The Center integrates traditional epidemiology with genetic analysis and clinical investigation to explore all phases of diseases of the nervous system. For more information about these centers visit: http://www.cumc.columbia.edu/dept/taub/,

http://www.cumc.columbia.edu/dept/sergievsky/

The Center for Motor Neuron Biology and Disease (MNC) at Columbia University Medical Center brings together 40 basic and clinical research groups working on different aspects of motor neuron biology and disease, including spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). MNC members are housed in various departments throughout the Columbia University and Columbia University Medical Center campuses, to draw upon the unique range and depth of expertise in this multidisciplinary field at Columbia. MNC researchers and clinicians study basic motor neuron biology in parallel with disease models and clinical trials in ALS and SMA. For more information about MNC visit: www.ColumbiaMNC.org

Columbia University Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, pre-clinical and clinical research, in medical and health sciences education, and in patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Established in 1767, Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons was the first institution in the country to grant the M.D. degree and is among the most selective medical schools in the country. Columbia University Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest in the United States.

Two genes that cause familial ALS shown to work together

2011-09-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cornell physicists capture microscopic origins of thinning and thickening fluids

2011-09-02

ITHACA, N.Y. – In things thick and thin: Cornell physicists explain how fluids – such as paint or paste - behave by observing how micron-sized suspended particles dance in real time. Using high-speed microscopy, the scientists unveil how these particles are responding to fluid flows from shear – a specific way of stirring. (Science, Sept. 2).

Observations by Xiang Cheng, Cornell post-doctoral researcher in physics and Itai Cohen, Cornell associate professor of physics, are the first to link direct imaging of the particle motions with changes in liquid viscosity.

Combining ...

UT MD Anderson scientists discover secret life of chromatin

2011-09-02

HOUSTON -- Chromatin - the intertwined histone proteins and DNA that make up chromosomes – constantly receives messages that pour in from a cell’s intricate signaling networks: Turn that gene on. Stifle that one.

But chromatin also talks back, scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center report today in the journal Cell, issuing orders affecting a protein that has nothing to do with chromatin's central role in gene transcription - the first step in protein formation.

"Our findings indicate chromatin might have another life as a direct signaling molecule, ...

ATS publishes clinical practice guidelines on interpretation of FENO levels

2011-09-02

The American Thoracic Society has issued the first-ever guidelines on the use of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) that address when to use FENO and how to interpret FENO levels in different clinical settings. The guidelines, which appear in the September 1 American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, are graded based on the available evidence in the literature.

"There are existing guidelines to measure FENO but none to interpret the results," noted Raed A. Dweik, MD, chair of the guideline writing committee and professor of medicine and director ...

New map shows where tastes are coded in the brain

2011-09-02

Each taste, from sweet to salty, is sensed by a unique set of neurons in the brains of mice, new research reveals. The findings demonstrate that neurons that respond to specific tastes are arranged discretely in what the scientists call a "gustotopic map." This is the first map that shows how taste is represented in the mammalian brain.

There's no mistaking the sweetness of a ripe peach for the saltiness of a potato chip – in part due to highly specialized, selectively-tuned cells in the tongue that detect each unique taste. Now, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and NIH ...

Ben-Gurion U. researchers identify gene that leads to myopia (nearsightedness)

2011-09-02

BEER-SHEVA, ISRAEL, September 1, 2011— A Ben-Gurion University of the Negev research group led by Prof. Ohad Birk has identified a gene whose defect specifically causes myopia or nearsightedness.

In an article appearing online in the American Journal of Human Genetics today, Birk and his team reveal that a mutation in LEPREL1 has been shown to cause myopia.

"We are finally beginning to understand at a molecular level why nearsightedness occurs," Prof. Birk says. The discovery was a group effort at BGU's Morris Kahn Laboratory of Human Genetics at the National Institute ...

2 brain halves, 1 perception

2011-09-02

Our brain is divided into two hemispheres, which are linked through only a few connections. However, we do not seem to have a problem to create a coherent image of our environment – our perception is not "split" in two halves. For the seamless unity of our subjective experience, information from both hemispheres needs to be efficiently integrated. The corpus callosum, the largest fibre bundle connecting the left and right side of our brain, plays a major role in this process. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt investigated whether ...

Faster progress through puberty linked to behavior problems

2011-09-02

Children who go through puberty at a faster rate are more likely to act out and to suffer from anxiety and depression, according to a study by researchers at Penn State, Duke University and the University of California, Davis. The results suggest that primary care providers, teachers and parents should look not only at the timing of puberty in relation to kids' behavior problems, but also at the tempo of puberty -- how fast or slow kids go through puberty.

"Past work has examined the timing of puberty and shown the negative consequences of entering puberty at an early ...

Sex hormones impact career choices

2011-09-02

Teacher, pilot, nurse or engineer? Sex hormones strongly influence people's interests, which affect the kinds of occupations they choose, according to psychologists.

"Our results provide strong support for hormonal influences on interest in occupations characterized by working with things versus people," said Adriene M. Beltz, graduate student in psychology, working with Sheri A. Berenbaum, professor of psychology and pediatrics, Penn State.

Berenbaum and her team looked at people's interest in occupations that exhibit sex differences in the general population and ...

First long-term study of WTC workers shows widespread health problems 10 years after Sept. 11

2011-09-02

In the first long-term study of the health impacts of the World Trade Center (WTC) collapse on September 11, 2001, researchers at The Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York have found substantial and persistent mental and physical health problems among 9/11 first responders and recovery workers. The data are published this week in a special 9/11 issue of the medical journal Lancet.

The Mount Sinai World Trade Center Clinical Center of Excellence and Data Center evaluated more than 27,000 police officers, construction workers, firefighters, and municipal workers over the ...

Caltech team says sporulation may have given rise to the bacterial outer membrane

2011-09-02

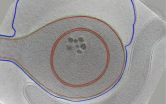

VIDEO:

This video uses animation to piece together cryotomograms of Acetonema longum cells at different stages of the sporulation process. Cryotomograms appear in black and white. Inner membranes are shown in...

Click here for more information.

PASADENA, Calif.—Bacteria can generally be divided into two classes: those with just one membrane and those with two. Now researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have used a powerful imaging technique to find ...