(Press-News.org) Converting sunlight into electricity is not economically attractive because of the high cost of solar cells, but a recent, purely optical approach to improving luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs) may ease the problem, according to researchers at Argonne National Laboratories and Penn State.

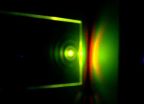

Using concentrated sunlight reduces the cost of solar power by requiring fewer solar cells to generate a given amount of electricity. LSCs concentrate light by absorbing and re-emiting it at lower frequency within the confines of a transparent slab of material. They can not only collect direct sunlight, but on cloudy days, can collect diffuse light as well. The material then guides the light to the slab's edges, where photovoltaic cells convert the energy to electricity.

"Currently, solar concentrators use expensive tracking systems that need to follow the sun," said Chris Giebink, assistant professor of electrical engineering, Penn State, formerly of Argonne National Laboratory. "If they are a few tenths of a degree off from perfection, the power output of the system drops drastically. If they could maintain high concentration without tracking the sun, they could create electricity more cheaply."

LSCs can do this, potentially concentrating light to the equivalent of more than 100 suns but, in practice, their output has been limited. While LSCs work well when small, their performance deteriorates with increasing size because much of the energy is reabsorbed before reaching the photovoltaics.

Typically, a little bit of light is reabsorbed each time it bounces around in the slab and, because this happens hundreds of times, it adds up to a big problem. The researchers, who included Giebink and Gary Widerrecht and Michael Wasielewski, Argonne-Northwestern Solar Energy Research Center and Northwestern University, note in the current issue of Nature Photonics that "we demonstrate near-lossless propagation for several different chromophores, which ultimately enables a more than twofold increase in concentration ratio over that of the corresponding conventional LSC."

The key to decreasing absorption is microcavity effects that occur when light travels through a small structure with a size comparable to the light's wavelength. These LSCs are made of two thin films on a piece of glass. The first thin film is a luminescent layer that contains a fluourescent dye capable of absorbing and re-emitting sunlight. This sits on a low refractive index layer that looks like air from the light's point of view. This combination makes the microcavity and changing the luminescent layer's thickness across the surface changes the microcavity's resonance. This means that light emitted from one location in the concentrator does not fit back into the luminescent film anywhere else, preventing it from being reabsorbed.

"We were looking for some way to admit the light, but keep it from being absorbed," said Giebink. "One of the things we could change was the shape and thickness of the luminescent layer."

The researchers tried an ordered stair step approach to the surface of the dye layer. They looked at the light output from this new configuration by placing a photovoltaic cell at one edge of the collector and found a 15 percent improvement compared to conventional LSCs.

"Experimentally we are working with devices the size of microscope slides, but we modeled the output for larger, more practical sizes," said Giebink. "Extending out results with the model predicts intensification to 25 suns for a window pane sized collector. This is about two and a half times higher than a conventional LSC."

The researchers do not believe that the stair step approach is the optimal design for these LSCs. A more complicated surface variation is probably even better, but designing that will take more modeling. Other approaches may also include varying the shape of the glass substrate, which would produce a similar effect and potentially be simpler to make.

"We need to find the optimum way to structure this new type of LSC so that it is more efficient but also very inexpensive to make," said Giebink.

INFORMATION:

The U.S. Department of Energy supported this work. Argonne National Laboratory has filed for a patent on this application.

Solar concentrator increases collection with less loss

2011-11-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Animal study suggests that newborn period may be crucial time to prevent later diabetes

2011-11-03

Pediatric researchers who tested newborn animals with an existing human drug used in adults with diabetes report that this drug, when given very early in life, prevents diabetes from developing in adult animals. If this finding can be repeated in humans, it may become a way to prevent at-risk infants from developing type 2 diabetes.

"We uncovered a novel mechanism to prevent the later development of diabetes in this animal study," said senior author Rebecca A. Simmons, M.D., a neonatologist at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. "This may indicate that there is an ...

News tips from the journal mBio

2011-11-03

Antibodies Trick Bacteria into Killing Each Other

The dominant theory about antibodies is that they directly target and kill disease-causing organisms. In a surprising twist, researchers from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine have discovered that certain antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae actually trick the bacteria into killing each other.

Pneumococcal vaccines currently in use today target the pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide (PPS), a sort of armor that surrounds the bacterial cell, protecting it from destruction. Current thought hold that PPS-binding ...

Solar power could get boost from new light absorption design

2011-11-03

Solar power may be on the rise, but solar cells are only as efficient as the amount of sunlight they collect. Under the direction of a new professor at Northwestern University's McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science, researchers have developed a new material that absorbs a wide range of wavelengths and could lead to more efficient and less expensive solar technology.

A paper describing the findings, "Broadband polarization-independent resonant light absorption using ultrathin plasmonic super absorbers," was published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

"The ...

Exenatide (Byetta) has rapid, powerful anti-inflammatory effect, UB study shows

2011-11-03

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Exenatide, a drug commonly prescribed to help patients with type 2 diabetes improve blood sugar control, also has a powerful and rapid anti-inflammatory effect, a University at Buffalo study has shown.

The study of the drug, marketed under the trade name Byetta, was published recently in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

"Our most important finding was this rapid, anti-inflammatory effect, which may lead to the inhibition of atherosclerosis, the major cause of heart attacks, strokes and gangrene in diabetics," says Paresh Dandona, ...

Manufacturing microscale medical devices for faster tissue engineering

2011-11-03

WASHINGTON, Nov. 2—In the emerging field of tissue engineering, scientists encourage cells to grow on carefully designed support scaffolds. The ultimate goal is to create living structures that might one day be used to replace lost or damaged tissue, but the manufacture of appropriately detailed scaffolds presents a significant challenge that has kept most tissue engineering applications confined to the research lab. Now a team of researchers from the Laser Zentrum Hannover (LZH) eV Institute in Hannover, Germany, and the Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at the ...

Dirt prevents allergy

2011-11-03

Oversensitivity diseases, or allergies, now affect 25 per cent of the population of Denmark. The figure has been on the increase in recent decades and now researchers at the Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood (COPSAC), University of Copenhagen, are at last able to partly explain the reasons.

"In our study of over 400 children we observed a direct link between the number of different bacteria in their rectums and the risk of development of allergic disease later in life," says Professor Hans Bisgaard, consultant at Gentofte Hospital, head of the Copenhagen ...

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance now an important first-line test

2011-11-03

Philadelphia, PA, November 2, 2011 – Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) has undergone substantial development and offers important advantages compared with other well-established imaging modalities. In the November/December issue of Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, published by Elsevier, a series of articles on key topics in CMR will foster greater understanding of the rapidly expanding role of CMR in clinical cardiology.

"Until a decade ago, CMR was considered mostly a research tool, and scans for clinical purpose were rare," stated guest editors Theodoros ...

Thousand-color sensor reveals contaminants in Earth and sea

2011-11-03

The world may seem painted with endless color, but physiologically the human eye sees only three bands of light — red, green, and blue. Now a Tel Aviv University-developed technology is using colors invisible to the naked eye to analyze the world we live in. With the ability to detect more than 1,000 colors, the "hyperspectral" (HSR) camera, like Mr. Spock's sci-fi "Tricorder," is being used to "diagnose" contaminants and other environmental hazards in real time.

Prof. Eyal Ben-Dor of TAU's Department of Geography and the Human Environment says that reading this extensive ...

Rutgers neuroscientist says protein could prevent secondary damage after stroke

2011-11-03

One of two proteins that regulate nerve cells and assist in overall brain function may be the key to preventing long-term damage as a result of a stroke, the leading cause of disability and third leading cause of death in the United States.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Neuroscience, Bonnie Firestein, professor of cell biology and neuroscience, in the School of Arts and Sciences, says the new research indicates that increased production of two proteins – cypin and PSD-95 – results in very different outcomes.

While cypin – a protein that regulates nerve ...

Study reveals details of alternative splicing circuitry that promotes cancer's Warburg effect

2011-11-03

Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – Cancer cells maintain their life-style of extremely rapid growth and proliferation thanks to an enzyme called PK-M2 (pyruvate kinase M2) that alters the cells' ability to metabolize glucose – a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect.

Professor Adrian Krainer, Ph.D., and his team at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), who seek to reverse this effect and force cancer cells to regain the metabolism of normal cells, have discovered details of molecular events that cause cancer cells to produce PK-M2 instead of its harmless counterpart, an isoform ...