(Press-News.org) Why do people with a hereditary mutation of the red blood pigment hemoglobin (as is the case with sickle-cell anemia prevalent in Africa) not contract severe malaria? Scientists in the group headed by Prof. Michael Lanzer of the Department of Infectious Diseases at Heidelberg University Hospital have now solved this mystery. A degradation product of the altered hemoglobin provides protection from severe malaria. Within the red blood cells infected by the malaria parasite, it blocks the establishment of a trafficking system used by the parasite's special adhesive proteins – adhesins – to access the exterior of the blood cells. As a result, the infected blood cells do not adhere to the vessel walls, as is usually the case for this type of malaria. This means that no dangerous circulatory disorders or neurological complications occur. The research study has been published in the journal Science, appearing initially online.

In the 1940s, researchers already discovered that sickle-cell anemia with its characteristic blood mutation was particularly prevalent in certain population groups in Africa. They also survived malaria tropica, whose course is usually especially virulent. With malaria tropica, the malaria parasites (Plasmodia) enter the person after a bite of an infected Anopheles mosquito. The mosquito first multiplies in the person's liver cells and then infects the red blood cells (erythrocytes). Once inside the erythrocytes, they divide again and ultimately destroy them. The nearly simultaneous bursting of all infected blood cells causes the characteristic symptoms, which include bouts of fever and anemia.

Adhesins on red blood cells cause circulatory disorders

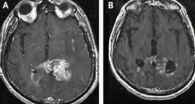

In patients with malaria tropica, neurological complications such as paralysis, seizures, coma and severe brain damage also frequently occur. This is caused by an anomaly of the parasite Plasmodium falciparum. It forms special adhesins that reach the cell surface of the infected blood cell. Once there, it causes the erythrocytes to adhere to the vessel walls, preventing them from being recognized in the spleen as damaged and removed from circulation. The parasite's protective mechanism results in smaller vessels closing, becoming inflamed and for example, prevents parts of the nervous system from being adequately supplied with oxygen.

In humans with mutated hemoglobin, these complications occur in a weakened form or not at all. "At the cell surface of infected erythrocytes with mutated hemoglobin, there are significantly fewer adhesins of the parasite than in normal red blood cells," explained Prof. Lanzer, Director of the Dept. of Infectious Diseases, Parasitology. "For this reason, we had a closer look at the trafficking system within the host cell." To this end, the team compared the blood cells with normal hemoglobin and two hemoglobin variants (hemoglobin S and hemoglobin C), which occur in around one-fifth of the African population in malaria-infected areas.

Trafficking system of the malaria parasite visualized for the first time

In so doing, the scientists used high-resolution microscopy techniques such as cryoelectron tomography to discover a new transport mechanism. The parasite uses a certain protein (actin) from the cytoskeleton (cellular skeleton) of the erythrocytes for its own trafficking network. "It forms a completely new structure that has nothing in common with the rest of the cytoskeleton," explained Dr. Marek Cyrklaff, group leader at the Dept. of Infectious Diseases, Parasitology and first author of the article. "The vesicles with the adhesins reach the cell surface of the red blood cells directly via these actin filaments."

In contrast to erythrocytes with the two hemoglobin variants, here only short pieces of actin filaments are found. Targeted transport to the surface is not possible. "The entire transport system of the malaria parasite is degenerated in these blood cells," Cyrklaff added. Laboratory tests showed that the hemoglobins themselves were not responsible for this, but rather a degradation product, ferryl hemoglobin. This is an irreversibly damaged, chemically altered hemoglobin that is no longer able to bind oxygen. The hemoglobins S and C are considerably more unstable than normal hemoglobin. As a result, blood cells with these variants contain ten times more ferryl hemoglobin than other erythrocytes. This high concentration destabilizes the binding of the actin structure and it disintegrates.

"With these results, we have now described a molecular mechanism for the first time that explains this hemoglobin variant's protective effect against malaria," Lanzer said.

INFORMATION:

Literature:

Hemoglobins S and C interfere with Actin Remodeling in Plasmodium falciparum-Infected Erythrocytes: Marek Cyrklaff, Cecilia P. Sanchez, Nicole Kilian, Cyrille Bisseye, Jacques Simpore, Friedrich Frischknecht and Michael Lanzer. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.1213775

Heidelberg University Hospital and Medical Faculty:

Internationally recognized patient care, research, and teaching

Heidelberg University Hospital is one of the largest and most prestigious medical centers in Germany. The Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University belongs to the internationally most renowned biomedical research institutions in Europe. Both institutions have the common goal of developing new therapies and implementing them rapidly for patients. With about 10,000 employees, training and qualification is an important issue. Every year, around 550,000 patients are treated on an inpatient or outpatient basis in more than 50 clinics and departments with 2,000 beds. Currently, about 3,600 future physicians are studying in Heidelberg; the reform Heidelberg Curriculum Medicinale (HeiCuMed) is one of the top medical training programs in Germany.

Requests by journalists:

Prof. Michael Lanzer, Ph. D.

University Hospital of Heidelberg

Dept. of Infectious Diseases, Parasitology

Im Neuenheimer Feld 324

D-69120 Heidelberg

Germany

phone: 49-6221-567845

fax: 49-6221-564643

e-mail: michael.lanzer@med.uni-heidelberg.de

Dr. Annette Tuffs

Head of Public Relations and Press Department

University Hospital of Heidelberg and

Medical Faculty of Heidelberg

Im Neuenheimer Feld 672

D-69120 Heidelberg

Germany

phone: 49-6221-56-45-36

fax: 49-6221-56-45-44

e-mail: annette.tuffs@med.uni-heidelberg.de

Selected english press releases online:

http://www.klinikum.uni-heidelberg.de/presse

Protection from severe malaria explained

Defective hemoglobin prevents the establishment of an important transport system of the malaria parasite in infected blood cells- Heidelberg researchers' results published in Science

2011-11-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Chalmers scientists create light from vacuum

2011-11-21

Scientists at Chalmers University of Technology have succeeded in creating light from vacuum – observing an effect first predicted over 40 years ago. The results is published tomorrow (Wednesday) in the journal Nature. In an innovative experiment, the scientists have managed to capture some of the photons that are constantly appearing and disappearing in the vacuum.

The experiment is based on one of the most counterintuitive, yet, one of the most important principles in quantum mechanics: that vacuum is by no means empty nothingness. In fact, the vacuum is full of various ...

Enzymatic synthesis of pyrrolysine, the mysterious 22nd amino acid

2011-11-21

This press release is available in German.

With few exceptions, all known proteins are built up from only twenty amino acids. 25 years ago scientists discovered a 21st amino acid, selenocysteine and ten years ago a 22nd, the pyrrolysine. However, how the cell produces the unusual building block remained a mystery. Now researchers at the Technische Universitaet Muenchen have elucidated the structure of an important enzyme in the production of pyrrolysine. The scientific journal Angewandte Chemie reports on their results in its "Early View" online section.

Proteins ...

MU researchers develop tool that saves time, eliminates mistakes in diabetes care

2011-11-21

COLUMBIA, Mo. – In the fast-paced world of health care, doctors are often pressed for time during patient visits. Researchers at the University of Missouri developed a tool that allows doctors to view electronic information about patients' health conditions related to diabetes on a single computer screen. A new study shows that this tool, the diabetes dashboard, saves time, improves accuracy and enhances patient care.

The diabetes dashboard provides information about patients' vital signs, health conditions, current medications, and laboratory tests that may need to be ...

Colon cancer screening campaign erases racial, gender gaps in use of colonoscopy

2011-11-21

Since the 1970s, U.S. mortality rates due to colorectal cancer have declined overall, yet among blacks and Hispanics, the death rates rose. Evidence suggests that underuse of colonoscopy screening among these groups is one reason for the large disparities. In 2003, New York City launched a multifaceted campaign to improve colonoscopy rates among racial and ethnic minorities and women. A new study conducted by researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health and the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene demonstrates the notable success of the campaign. ...

A corny turn for biofuels from switchgrass

2011-11-21

Many experts believe that advanced biofuels made from cellulosic biomass are the most promising alternative to petroleum-based liquid fuels for a renewable, clean, green, domestic source of transportation energy. Nature, however, does not make it easy. Unlike the starch sugars in grains, the complex polysaccharides in the cellulose of plant cell walls are locked within a tough woody material called lignin. For advanced biofuels to be economically competitive, scientists must find inexpensive ways to release these polysaccharides from their bindings and reduce them to fermentable ...

Great Plains river basins threatened by pumping of aquifers

2011-11-21

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Suitable habitat for native fishes in many Great Plains streams has been significantly reduced by the pumping of groundwater from the High Plains aquifer – and scientists analyzing the water loss say ecological futures for these fishes are "bleak."

Results of their study have been published in the journal Ecohydrology.

Unlike alluvial aquifers, which can be replenished seasonally with rain and snow, these regional aquifers were filled by melting glaciers during the last Ice Age, the researchers say. When that water is gone, it won't come back – at ...

Old drugs find new target for treating brain tumor

2011-11-21

Scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center, in collaboration with colleagues in Boston and South Korea, say they have identified a novel gene mutation that causes at least one form of glioblastoma (GBM), the most common type of malignant brain tumor.

The findings are reported in the online edition of the journal Cancer Research.

Perhaps more importantly, the researchers found that two drugs already being used to treat other forms of cancer effectively prolonged the survival of mice modeling this particular ...

GOES satellite eyeing late season lows for tropical development

2011-11-21

Its late in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific hurricane seasons, but the calendar isn't stopping the tropics. The GOES-13 satellite is keeping forecasters informed about developing lows like System 90E in the eastern Pacific and another low pressure area in the Atlantic.

System 90E and the Atlantic low pressure area were both captured in one image from the NOAA's GOES-13 satellite today, November 18, 2011 at 1145 UTC (7:45 a.m. EST). The image was created by the NASA GOES Project (in partnership with NOAA) at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The ...

New NASA missions to investigate how Mars turned hostile

2011-11-21

Maybe because it appears as a speck of blood in the sky, the planet Mars was named after the Roman god of war. From the point of view of life as we know it, that's appropriate. The Martian surface is incredibly hostile for life. The Red Planet's thin atmosphere does little to shield the ground against radiation from the Sun and space. Harsh chemicals, like hydrogen peroxide, permeate the soil. Liquid water, a necessity for life, can't exist for very long here --any that does not quickly evaporate in the diffuse air will soon freeze out in subzero temperatures common over ...

Walking through doorways causes forgetting, new research shows

2011-11-21

We've all experienced it: The frustration of entering a room and forgetting what we were going to do. Or get. Or find.

New research from University of Notre Dame Psychology Professor Gabriel Radvansky suggests that passing through doorways is the cause of these memory lapses.

"Entering or exiting through a doorway serves as an 'event boundary' in the mind, which separates episodes of activity and files them away," Radvansky explains.

"Recalling the decision or activity that was made in a different room is difficult because it has been compartmentalized."

The study ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] Protection from severe malaria explainedDefective hemoglobin prevents the establishment of an important transport system of the malaria parasite in infected blood cells- Heidelberg researchers' results published in Science