(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON– In recent decades, the rate at which humans worldwide are pumping dry the vast underground stores of water that billions depend on has more than doubled, say scientists who have conducted an unusual, global assessment of groundwater use.

These fast-shrinking subterranean reservoirs are essential to daily life and agriculture in many regions, while also sustaining streams, wetlands, and ecosystems and resisting land subsidence and salt water intrusion into fresh water supplies. Today, people are drawing so much water from below that they are adding enough of it to the oceans (mainly by evaporation, then precipitation) to account for about 25 percent of the annual sea level rise across the planet, the researchers find.

Soaring global groundwater depletion bodes a potential disaster for an increasingly globalized agricultural system, says Marc Bierkens of Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and leader of the new study.

"If you let the population grow by extending the irrigated areas using groundwater that is not being recharged, then you will run into a wall at a certain point in time, and you will have hunger and social unrest to go with it," Bierkens warns. "That is something that you can see coming for miles."

He and his colleagues will publish their new findings in an upcoming issue of Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

In the new study, which compares estimates of groundwater added by rain and other sources to the amounts being removed for agriculture and other uses, the team taps a database of global groundwater information including maps of groundwater regions and water demand. The researchers also use models to estimate the rates at which groundwater is both added to aquifers and withdrawn. For instance, to determine groundwater recharging rates, they simulate a groundwater layer beneath two soil layers, exposed at the top to rainfall, evaporation, and other effects, and use 44 years worth of precipitation, temperature, and evaporation data (1958-2001) to drive the model.

Applying these techniques worldwide to regions ranging from arid areas to those with the wetness of grasslands, the team finds that the rate at which global groundwater stocks are shrinking has more than doubled between 1960 and 2000, increasing the amount lost from 126 to 283 cubic kilometers (30 to 68 cubic miles) of water per year. Because the total amount of groundwater in the world is unknown, it's hard to say how fast the global supply would vanish at this rate. But, if water was siphoned as rapidly from the Great Lakes, they would go bone-dry in around 80 years.

Groundwater represents about 30 percent of the available fresh water on the planet, with surface water accounting for only one percent. The rest of the potable, agriculture friendly supply is locked up in glaciers or the polar ice caps. This means that any reduction in the availability of groundwater supplies could have profound effects for a growing human population.

The new assessment shows the highest rates of depletion in some of the world's major agricultural centers, including northwest India, northeastern China, northeast Pakistan, California's central valley, and the midwestern United States.

"The rate of depletion increased almost linearly from the 1960s to the early 1990s," says Bierkens. "But then you see a sharp increase which is related to the increase of upcoming economies and population numbers; mainly in India and China."

As groundwater is increasingly withdrawn, the remaining water "will eventually be at a level so low that a regular farmer with his technology cannot reach it anymore," says Bierkens. He adds that some nations will be able to use expensive technologies to get fresh water for food production through alternative means like desalinization plants or artificial groundwater recharge, but many won't.

Most water extracted from underground stocks ends up in the ocean, the researchers note. The team estimates the contribution of groundwater depletion to sea level rise to be 0.8 millimeters per year, which is about a quarter of the current total rate of sea level rise of 3.1 millimeters per year. That's about as much sea-level rise as caused by the melting of glaciers and icecaps outside of Greenland and Antarctica, and it exceeds or falls into the high end of previous estimates of groundwater depletion's contribution to sea level rise, the researchers add.

###

Notes for Journalists

As of the date of this press release, the paper by Bierkens et al. is still "in press" (i.e. not yet published). Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this paper in press by clicking on this link:

http://www.agu.org/journals/pip/gl/2010GL044571-pip.pdf

Or, you may order a copy of the paper by emailing your request to Colin Schultz at cschultz@agu.org. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release are under embargo.

Images:

The following news release and accompanying images can be found at:

http://www.agu.org/news/press/pr_archives/2010/2010-30.shtml

Title:

"A worldwide view of groundwater depletion"

Contact information for the author:

Marc Bierkens, Utrecht University, Tel. + 31 6 48 35 58 10, Mail m.bierkens@geo.uu.nl

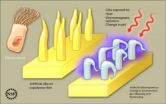

University of Southern Mississippi scientists recently imitated Mother Nature by developing, for the first time, a new, skinny-molecule-based material that resembles cilia, the tiny, hair-like structures through which organisms derive smell, vision, hearing and fluid flow.

While the new material isn't exactly like cilia, it responds to thermal, chemical, and electromagnetic stimulation, allowing researchers to control it and opening unlimited possibilities for future use.

This finding is published in today's edition of the journal Advanced Functional Materials. The ...

Archaeologists who interpret Stone Age culture from discoveries of ancient tools and artifacts may need to reanalyze some of their conclusions.

That's the finding suggested by a new study that for the first time looked at the impact of water buffalo and goats trampling artifacts into mud.

In seeking to understand how much artifacts can be disturbed, the new study documented how animal trampling in a water-saturated area can result in an alarming amount of disturbance, says archaeologist Metin I. Eren, a graduate student at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, and ...

University of California, Berkeley, and Yale University scientists have recreated the tremendous pressures and high temperatures deep in the Earth to resolve a long-standing puzzle: why some seismic waves travel faster than others through the boundary between the solid mantle and fluid outer core.

Below the earth's crust stretches an approximately 1,800-mile-thick mantle composed mostly of a mineral called magnesium silicate perovskite (MgSiO3). Below this depth, the pressures are so high that perovskite is compressed into a phase known as post-perovskite, which comprises ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report this month that MALAT1, a long non-coding RNA that is implicated in certain cancers, regulates pre-mRNA splicing – a critical step in the earliest stage of protein production. Their study appears in the journal Molecular Cell.

Nearly 5 percent of the human genome codes for proteins, and scientists are only beginning to understand the role of the rest of the "non-coding" genome. Among the least studied non-coding genes – which are transcribed from DNA to RNA but generally are not translated into proteins – are the long non-coding RNAs ...

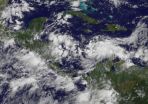

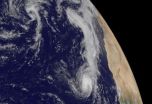

The fifteenth tropical depression of the Atlantic Ocean season has formed in the south-central Caribbean Sea, and the GOES-13 satellite captured its swirling mass of clouds and showers in a visible image today. Watches and warnings are already up for Central America.

At 2 p.m. EDT today, Sept. 23, Tropical Depression 15 had maximum sustained winds near 35 mph. It was located about 485 miles east of Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, near 13.9 North and 76.2 West. It was moving west at 15 mph, and had a minimum central pressure of 1007 millibars.

The government of Nicaragua ...

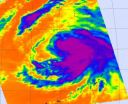

NASA's Aqua satellite has peered into the cloud tops of Tropical Storm Malakas and derived just how cold they really are, giving an indication to forecasters of the strength of the storm.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder instrument, known as AIRS has the ability to determine cloud top and sea surface temperatures from its position in space aboard NASA's Aqua satellite. Cloud top temperatures help forecasters know if a storm is powering up or powering down.

When cloud top temperatures get colder it means that they're getting higher into the atmosphere which means the ...

Tropical Depression Lisa has had a struggle, and it appears that she's in for more of the same.

Infrared satellite imagery from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite shows that the convection (rapidly rising air that forms thunderstorms that make up a tropical cyclone) is increasing in Lisa. The convection is becoming a little better organized and stronger which is will make for some heavy rainfall over the northwestern Cape Verde Islands. It's also an indication that she may be strengthening back into a tropical storm today.

That ...

Researchers have identified a gene that appears to increase a person's risk of developing late-onset Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of the disease. The gene, abbreviated as MTHFD1L, is on chromosome six, and was identified in a genome-wide association study. Details are published September 23 in the journal PLoS Genetics.

The collaborative team of researchers was led by Margaret A. Pericak-Vance, PhD, Director of the John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, ...

Pakistan is facing tremendous water issues. This summer's flooding has left millions of people without homes and without access to clean drinking water. But water issues - both quantity and quality - are not new to this strategically important country. Waterborne diseases account for 30 percent of all deaths in Pakistan, and kill some 250,000 children each year. Per capita water availability in Pakistan is less than one-ninth of what it is in the U.S. And what's more, researchers say if Pakistan doesn't manage its water resources differently, it's going to actually run ...

One touch directs a robotic arm to grab objects in a new computer program designed to give people in wheelchairs more independence.

University of Central Florida researchers thought the ease of the using the program's automatic mode would be a huge hit. But they were wrong – many participants in a pilot study didn't like it because it was "too easy."

Most participants preferred the manual mode, which requires them to think several steps ahead and either physically type in instructions or verbally direct the arm with a series of precise commands. They favored the manual ...