(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (February 22, 2012) – If you were to discover that a fundamental component of human biology has survived virtually intact for the past 25 million years, you'd be quite confident in saying that it is here to stay.

Such is the case for a team of Whitehead Institute scientists, whose latest research on the evolution of the human Y chromosome confirms that the Y—despite arguments to the contrary—has a long, healthy future ahead of it.

Proponents of the so-called rotting Y theory have been predicting the eventual extinction of the Y chromosome since it was first discovered that the Y has lost hundreds of genes over the past 300 million years. The rotting Y theorists have assumed this trend is ongoing, concluding that inevitably, the Y will one day be utterly devoid of its genetic content.

Over the past decade, Whitehead Institute Director David Page and his lab have steadily been churning out research that should have permanently debunked the rotting Y theory, but to no avail.

"For the past 10 years, the one dominant storyline in public discourse about the Y is that it is disappearing," says Page. "Putting aside the question of whether this ever had a sound scientific basis, the story went viral—fast—and has stayed viral. I can't give a talk without being asked about the disappearing Y. This idea has been so pervasive that it has kept us from moving on to address the really important questions about the Y."

To Page, this latest research represents checkmate in the chess match he's been drawn into against the "rotting Y" theorists. Members of his lab have dealt their fatal blow by sequencing the Y chromosome of the rhesus macaque—an Old World monkey whose evolutionary path diverged from that of humans some 25 million years ago—and comparing it with the sequences of the human and chimpanzee Y chromosomes. The comparison, published this week in the online edition of the journal Nature, reveals remarkable genetic stability on the rhesus and human Ys in the years since their evolutionary split.

Grasping the full impact of this finding requires a bit of historical context. Before they became specialized sex chromosomes, the X and Y were once an ordinary, identical pair of autosomes like the other 22 pairs of chromosomes humans carry. To maintain genetic diversity and eliminate potentially harmful mutations, autosome pairs swap genes with each other in a process referred to as "crossing over." Roughly 300 million years ago, a segment of the X stopped crossing over with the Y, causing rapid genetic decay on the Y. Over the next hundreds of millions of years, four more segments, or strata, of the X ceased crossing over with the Y. The resulting gene loss on the Y was so extensive that today, the human Y retains only 19 of the more than 600 genes it once shared with its ancestral autosomal partner.

"The Y was in free fall early on, and genes were lost at an incredibly rapid rate," says Page. "But then it leveled off, and it's been doing just fine since."

How fine? Well, the sequence of the rhesus Y, which was completed with the help of collaborators at the sequencing centers at Washington University School of Medicine and Baylor College of Medicine, shows the chromosome hasn't lost a single ancestral gene in the past 25 million years. By comparison, the human Y has lost just one ancestral gene in that period, and that loss occurred in a segment that comprises just 3% of the entire chromosome. The finding allows researchers to describe the Y's evolution as one marked by periods of swift decay followed by strict conservation.

"We've been carefully developing this clearcut way of demystifying the evolution of the Y chromosome," says Page lab researcher Jennifer Hughes, whose earlier work comparing the human and chimpanzee Ys revealed a stable human Y for at least six million years. "Now our empirical data fly in the face of the other theories out there. With no loss of genes on the rhesus Y and one gene lost on the human Y, it's clear the Y isn't going anywhere."

"This paper simply destroys the idea of the disappearing Y chromosome," adds Page. "I challenge anyone to argue when confronted with this data."

###

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Charles A. King Trust.

Written by Matt Fearer

David Page's primary affiliation is with Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where his laboratory is located and all his research is conducted. He is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and a professor of biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Full Citation:

"Strict evolutionary conservation followed rapid gene loss on human and rhesus Y chromosomes"

Nature, online February 22, 2012

Jennifer F. Hughes (1), Helen Skaletsky (1), Laura G. Brown (1), Tatyana Pyntikova (1), Tina Graves (2), Robert S. Fulton (2), Shannon Dugan (3), Yan Ding (3), Christian J. Buhay (3), Colin Kremitzki (2), Qiaoyan Wang (3), Hua Shen (3), Michael Holder (3), Donna Villasana (3), Lynne V. Nazareth (3), Andrew Cree (3), Laura Courtney (2), Joelle Veizer (2), Holland Kotkiewicz (2), Ting-Jan Cho (1), Natalia Koutseva (1), Steve Rozen (1), Donna M. Muzny (3), Wesley C. Warren (2), Richard A. Gibbs (3), Richard K. Wilson (2), David C. Page (1).

1. Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Whitehead Institute, and Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

2. The Genome Institute, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

3. Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

END

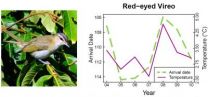

Bird migration timing across North America has been affected by climate change, according to a study published Feb. 22 in the open access journal PLoS ONE. The results are based on a systematic analysis of observations from amateur birdwatchers. This citizen science approach provided access to data for 18 common North American bird species, including orioles, house wrens, and barn swallows, across an unprecedented geographical region.

The researchers, led by Allen Hurlbert of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, found that the average arrival time for all species ...

Workers face many dangers on construction sites, including falls from heights and unsafe scaffolds or ladders. At any busy worksite, construction workers are also at risk of being struck by falling objects.

A recent New York Court of Appeals opinion, Wilinski v. 334 East 92nd Housing Development Fund, considered a worker's remedies for a Manhattan construction accident that occurred during demolition of a brick wall in a vacant warehouse. The worker suffered serious and lasting injuries when he was struck on the head, shoulder and arm by two ten-foot long, four-inch ...

Stress is known to lead to short-term escape behavior, and new research on elephants in South Africa shows that it can also cause long-term escape behavior, affecting the extent that elephants use their habitat. The work is published Feb. 22 in the open access journal PLoS ONE.

The researchers, led by David Jachowski of the University of Missouri, measured levels of FGM (fecal glucocorticoid metabolite), a proxy of physiological stress, and land use patterns for three different elephant populations, and found that higher FGM was associated with 20-43% lower land usage. ...

Like drivers in every other state, South Carolina motorists face their share of hazards that lead to car, truck and motorcycle accidents. From drunk drivers to dangerous roadways and defective tires or brakes, there are often several reasons why an accident occurred and people suffered injuries.

One common factor from coast to coast: inexperienced drivers pose more than their share of risks to themselves and other motorists and passengers as they learn to drive in various types of weather and traffic. A recent study published by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety ...

Nanoparticles have many useful applications, but also raise some potential health and ecological concerns. Now, new research shows that plastic nanoparticles are transported through the aquatic food chain and affect fish metabolism and behavior. The full report is published Feb. 22 in the open access journal PLoS ONE.

Exposing fish to nanoparticles slowed their feeding behavior, and also affected metabolic parameters including weight loss and cholesterol levels and distribution. The authors, led by Tommy Cedervall, Lars-Anders Hansson and Sara Linse of Lund University ...

Researchers have discovered an extremely old anthropomorphic figure engraved in rock in Brazil, according to a report published Feb. 22 in the open access journal PLoS ONE. The petroglyph, which dates to between 9,000 and 12,000 years old, is the oldest reliably dated instance of such rock art yet found in the Americas.

Art from this time period in the New World is quite rare, so little is known about the diversity of symbolic thinking of the early American settlers. The authors of this study, led by Walter Neves of the University of Sao Paulo, write that their findings ...

A fundamental discovery reported in the March 1st issue of the journal Nature, uncovers the first molecular evidence linking the body's natural circadian rhythms to sudden cardiac death (SCD). Ventricular arrhythmias, or abnormal heart rhythms, are the most common cause of sudden cardiac death: the primary cause of death from heart disease. They occur most frequently in the morning waking hours, followed by a smaller peak in the evening hours. While scientists have observed this tendency for many years, prior to this breakthrough, the molecular basis for these daily patterns ...

Florida is the deadliest state in the nation for pedestrians and is extremely dangerous for cyclists, according to a national study in USA Today.

The Miami area is especially prone to many of the accidents and injuries associated with high density pedestrian, cyclist and motorist traffic. The Florida Department of Transportation (DOT) is bringing awareness and a sense of urgency to the issue through its new public bicycle and pedestrian accident campaign.

Important Statistics Regarding Cyclist and Pedestrian Injuries and Fatalities

According to a national study ...

HOUSTON -- (Feb. 23, 2012) – Sudden cardiac death –catastrophic and unexpected fatal heart stoppage – is more likely to occur shortly after waking in the morning and in the late night.

In a report in the journal Nature (http://www.nature.com/nature/index.html), an international consortium of researchers that includes Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine (http://casemed.case.edu/) in Cleveland and Baylor College of Medicine (www.bcm.edu) explains the molecular linkage between the circadian clock and the deadly heart rhythms that lead to sudden death.

The ...

Uncovering the network of genes regulated by a crucial molecule involved in cancer called mTOR, which controls protein production inside cells, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have discovered how a protein "master regulator" goes awry, leading to metastasis, the fatal step of cancer.

Their work also pinpoints why past drugs that target mTOR have failed in clinical trials, and suggests that a new class of drugs now in trials may be more effective for the lethal form of prostate cancer for which presently there is no cure.

Described this ...