(Press-News.org) Harvard stem cell researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have taken a critical step in making possible the discovery in the relatively near future of a drug to control cystic fibrosis (CF), a fatal lung disease that claims about 500 lives each year, with 1,000 new cases diagnosed annually.

Beginning with the skin cells of patients with CF, Jayaraj Rajagopal, MD, and colleagues first created induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, and then used those cells to create human disease-specific functioning lung epithelium, the tissue that lines the airways and is the site of the most lethal aspect of CF, where the genes cause irreversible lung disease and inexorable respiratory failure.

That tissue, which researchers now can grow in unlimited quantities in the laboratory, contains the delta-508 mutation, the gene responsible for about 70 percent of all CF cases and 90 percent of the ones in the United States. The tissue also contains the G551D mutation, a gene that is involved in about 2 percent of CF cases and the one cause of the disease for which there is now a drug.

The work is featured on the cover of this month's Cell Stem Cell journal, which appeared online today. Postdoctoral fellow Hongmei Mou, PhD, is first author on the paper, and Rajagopal is the senior author.

Mou credits learning the underlying developmental biology in mice as the key to making tremendous progress in only two years. "I was able to apply these lessons to the iPS cell systems," she said. "I was pleasantly surprised the research went so fast, and it makes me excited to think important things are within reach. It opens up the door to identifying new small molecules [drugs] to treat lung disease."

Doug Melton, PhD, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI http://www.hsci.harvard.edu/), said, "This work makes it possible to produce millions of cells for drug screening, and for the first time human patients' cells can be used as the target." Melton, who is also co-chair of Harvard's inter-School Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology and is the Xander University Professor, added, "I would expect to see rapid progress in this area now that human cells, the very cells that are defective in the disease, can be used for screening."

Rajagopal said, "The key to our success was the ecosystem of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and MGH. HSCI investigators pioneered the strategies we used, helped us at the bench, and gave us advice on how to combine our knowledge of lung development with their exciting new platforms. Indeed, we also enjoyed a wonderful collaboration with Darrell Kotton's lab at Boston University that was able to convert mouse cells into lung tissue. These interactions really helped fuel us ahead."

The epithelial tissue created by Rajagopal and his colleagues at the MGH Center for Regenerative Medicine (http://www.massgeneral.org/regenmed/) also provides researchers with the same cells that are involved in a number of common lung conditions, including asthma, lung cancer, and chronic bronchitis, and may hasten the development of new insights and treatments into those conditions as well.

"We're not talking about a cure for CF; we're talking about a drug that hits the major problem in the disease. This is the enabling technology that will allow that to happen in a matter of years," said Rajagopal, a Harvard Medical School assistant professor of Medicine.

Also a physician trained as a pulmonologist, the specialty that treats CF patients, Rajagopal said, "When we talk about research and advances, donors and patients ask: 'When? How soon?' And we usually hesitate to answer. But we now have every single piece we need for the final push. So I have every hope that we'll have a therapy in a matter of years."

Cystic fibrosis, which used to claim its victims in infancy or early childhood, has evolved into a killer of those in their 30s because treatments of the infections that characterize the disease have improved. But despite those advances, there has been little progress in treating the underlying condition that affects the vast majority of patients: a defect in a single gene that interferes with the fluid balance in the surface layers of the airways and leads to a thickening of mucus, difficulty breathing and repeated infections and hospitalizations.

The discovery and recent FDA approval of the drug Ivacaftor, which corrects the G551D defect seen in about 2 percent of CF patients, has served as a proof of concept to demonstrate that the disease can be attacked with a conventional molecular treatment. In fact, Ivacaftor was found by screening thousands of drugs on a far less than ideal cell line. In the end, many drugs that functioned well on this cell line proved ineffective when used on genuine human airway tissue.

Genuine human airway tissue is the gold standard prior to drugs being tested clinically, but it has been extremely difficult to obtain the tissue from patients, and when it could be obtained, the tissue rarely survived long in the lab – all of which created a major bottleneck in screening for a therapy. But by creating iPS cells that contain the entire genome of a CF patient and directing those cells to develop into lung progenitor cells, which then develop into epithelium, the group appears to have solved this key problem.

Rajagopal, who did his own postdoctoral fellowship in Melton's laboratory during the first half of the past decade after completing his training in pulmonary medicine, said that having both the G551D and 508 genes in the epithelial tissue provides a way to prove that the tissue will be effective in testing drugs against CF.

"We've created the perfect cell line to show that the drug out there that works against G551D mutation works in this system, and then we're in business to screen for a drug against delta 508," he said. "We'll know soon that the cell line works. We know it makes bonafide airway epithelium, and we'll have the proof of principle that the tissue responds properly to the only known drug. We think this is the near-ideal tissue platform to find a drug for the majority of CF."

Rajagopal's lab has created numerous other cell lines to further show that a CF drug that works in one patient should work in others and to see whether this will be an area that allows a more personalized approach to medicine.

"I'm most looking forward to working with the community of pulmonologists that concentrate in CF to generate therapies. This is occurring more than two decades after the remarkable work that identified the CF gene. Looking forward, I'm very excited that CF may lead the way in lung disease once more, by demonstrating that our iPS platform can be used to probe the diseases that are much less well understood. CF has more than two decades of great biology behind it. The reason we chose to attack this disease first was because of that pioneering work that lets us use our system with a very firm foundation," Rajagopal said.

###The Harvard Stem Cell Institute is a collaborative of more than 1000 scientists throughout Harvard and its affiliated hospitals and Institutes, dedicated to using the fruits of stem cell biology to advance cures and treatments for human diseases and the degeneration associated with aging.

Massachusetts General Hospital (www.massgeneral.org), founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $750 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine.

Big advance against cystic fibrosis

Stem cell researchers create lung surface tissue in a dish

2012-04-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists discover new threat to birds posed by invasive pythons

2012-04-10

Smithsonian scientists and their colleagues have uncovered a new threat posed by invasive Burmese pythons in Florida and the Everglades: The snakes are not only eating the area's birds, but also the birds' eggs straight from the nest. The results of this research add a new challenge to the area's already heavily taxed native wildlife. The team's findings are published in the online journal Reptiles & Amphibians: Conservation and Natural History.

Burmese pythons, native to southern Asia, have taken up a comfortable residence in the state of Florida, especially in the Everglades. ...

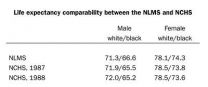

Study reveals impact of socioeconomic factors on the racial gap in life expectancy

2012-04-10

Differences in factors such as income, education and marital status could contribute overwhelmingly to the gap in life expectancy between blacks and whites in the United States, according to one of the first studies to put a number on how much of the divide can be attributed to disparities in socioeconomic characteristics.

A Princeton University study recently published in the journal Demography reveals that socioeconomic differences can account for 80 percent of the life-expectancy divide between black and white men, and for 70 percent of the imbalance between black ...

Researchers discover unique suspension technique for large-scale stem cell production

2012-04-10

Post-doctoral researcher David Fluri and Professor Peter Zandstra at the University of Toronto's Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering (IBBME) have developed a unique new technique for growing stem cells that may make possible cost-effective, large-scale stem cell manufacturing and research.

Although stem cells are widely used for the testing of new drugs, researchers have always faced difficulties manufacturing enough viable cells from a culture. Typically, stem cells are grown on surfaces that must be scraped, and which must then be differentiated from ...

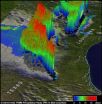

NASA's TRMM Satellite sees tornadic Texas storms in 3-D

2012-04-10

NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite provides a look at thunderstorms in three dimensions and shows scientists the heights of the thunderclouds and the rainfall rates coming from them, both of which indicate severity.

Powerful thunderstorms that created severe weather were more than 8 miles high.

NOAA's National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center received 18 reports of tornadoes occurring on April 3 over northeastern Texas. Some of these very destructive storms dropped softball sized hail as they passed to the south of the Dallas/Fort ...

Women cannot rewind the 'biological clock'

2012-04-10

Many women do not fully appreciate the consequences of delaying motherhood, and expect that assisted reproductive technologies can reverse their aged ovarian function, Yale researchers reported in a study published in a recent issue of Fertility and Sterility.

"There is an alarming misconception about fertility among women," said Pasquale Patrizio, M.D., professor in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Yale School of Medicine and director of the Yale Fertility Center. "We also found a lack of knowledge about steps women can take early in their reproductive ...

Salk scientists redraw the blueprint of the body's biological clock

2012-04-10

La Jolla, CA----The discovery of a major gear in the biological clock that tells the body when to sleep and metabolize food may lead to new drugs to treat sleep problems and metabolic disorders, including diabetes.

Scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, led by Ronald M. Evans, a professor in Salk's Gene Expression Laboratory, showed that two cellular switches found on the nucleus of mouse cells, known as REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ, are essential for maintaining normal sleeping and eating cycles and for metabolism of nutrients from food.

The findings, ...

Which plants will survive droughts, climate change?

2012-04-10

New research by UCLA life scientists could lead to predictions of which plant species will escape extinction from climate change.

Droughts are worsening around the world, posing a great challenge to plants in all ecosystems, said Lawren Sack, a UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and senior author of the research. Scientists have debated for more than a century how to predict which species are most vulnerable.

Sack and two members of his laboratory have made a fundamental discovery that resolves this debate and allows for the prediction of how diverse ...

Long-term studies detect effects of disappearing snow and ice

2012-04-10

Ecosystems are changing worldwide as a result of shrinking sea ice, snow, and glaciers, especially in high-latitude regions where water is frozen for at least a month each year—the cryosphere. Scientists have already recorded how some larger animals, such as penguins and polar bears, are responding to loss of their habitat, but research is only now starting to uncover less-obvious effects of the shrinking cryosphere on organisms. An article in the April issue of BioScience describes some impacts that are being identified through studies that track the ecology of affected ...

Long-term research reveals causes and consequences of environmental change

2012-04-10

WASHINGTON, D.C., APRIL 6, 2012—As global temperatures rise, the most threatened ecosystems are those that depend on a season of snow and ice, scientists from the nation's Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network say."The vulnerability of cool, wet areas to climate change is striking," says Julia Jones, a lead author in a special issue of the journal BioScience released today featuring results from more than 30 years of LTER, a program of the National Science Foundation (NSF).

In semi-arid regions like the southwestern United States, mountain snowpacks are the dominant ...

Long-term neuropsychological impairment is common in acute lung injury survivors

2012-04-10

Cognitive and psychiatric impairments are common among long-term survivors of acute lung injury (ALI), and these impairments can be assessed using a telephone-based test battery, according to a new study.

"Neuropsychological impairment is increasingly being recognized as an important outcome among survivors of critical illness, but neuropsychological function in long-term ALI survivors has not been assessed in a multi-center trial, and evidence on the etiology of these impairments in ALI survivors is limited," said lead author Mark E. Mikkelsen, MD, MSCE, assistant professor ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

[Press-News.org] Big advance against cystic fibrosisStem cell researchers create lung surface tissue in a dish