(Press-News.org) SALT LAKE CITY, April 30, 2012 – Cochlear implants have restored basic hearing to some 220,000 deaf people, yet a microphone and related electronics must be worn outside the head, raising reliability issues, preventing patients from swimming and creating social stigma.

Now, a University of Utah engineer and colleagues in Ohio have developed a tiny prototype microphone that can be implanted in the middle ear to avoid such problems.

The proof-of-concept device has been successfully tested in the ear canals of four cadavers, the researchers report in a study just published online in the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers journal Transactions on Biomedical Engineering.

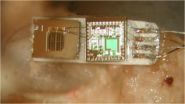

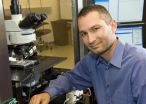

The prototype – about the size of an eraser on a pencil – must be reduced in size and improved in its ability to detect quieter, low-pitched sounds, so tests in people are about three years away, says the study's senior author, Darrin J. Young, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Utah and USTAR, the Utah Science Technology and Research initiative.

The study showed incoming sound is transmitted most efficiently to the microphone if surgeons first remove the incus or anvil – one of three, small, middle-ear bones. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval would be needed for an implant requiring such surgery.

The current prototype of the packaged, middle-ear microphone measures 2.5-by-6.2 millimeters (roughly one-tenth by one-quarter inch) and weighs 25 milligrams, or less than a thousandth of an ounce. Young wants to reduce the package to 2-by-2 millimeters.

Young, who moved the Utah in 2009, conducted the study with Mark Zurcher and Wen Ko, who are his former electrical engineering colleagues at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, and with ear-nose-throat physicians Maroun Semaan and Cliff Megerian of University Hospitals Case Medical Center.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH-DC-006850).

Problems with External Parts on Cochlear Implants

The National Institutes of Health says almost 220,000 people worldwide with profound deafness or severe hearing impairment have received cochlear implants, about one-third of them in the United States, where two-fifths of the recipients are children.

In conventional cochlear implant, there are three main parts that are worn externally on the head behind the ear: a microphone to pick up sound, a speech processor and a radio transmitter coil. Implanted under the skin behind the ear are a receiver and stimulator to convert the sound signals into electric impulses, which then go through a cable to between four and 16 electrodes that wind through the cochlea of the inner ear and stimulate auditory nerves so the patient can hear.

"It's a disadvantage having all these things attached to the outside" of the head, Young says. "Imagine a child wearing a microphone behind the ear. It causes problems for a lot of activities. Swimming is the main issue. And it's not convenient to wear these things if they have to wear a helmet."

Young adds that "for adults, it's social perception. Wearing this thing indicates you are somewhat handicapped and that actually prevents quite a percentage of candidates from getting the implant. They worry about the negative image."

As for reliability, "if you have wires connected from the microphone to the coil, those wires can break," he says.

How Sound Moves in Normal Ears, Cochlear Implants and the New Device

Sound normally moves into the ear canal and makes the eardrum vibrate. At what is known as the umbo, the eardrum connects to a chain of three tiny bones: the malleus, incus and stapes, also known as the hammer, anvil and stirrup. The bones vibrate. The stapes or stirrup touches the cochlea, the inner ear's fluid-filled chamber. Hair cells (not really hair) on the cochlea's inner membrane move, triggering the release of a neurotransmitter chemical that carries the sound signals to the brain.

In profoundly deaf people who are candidates for cochlear implants, the hair cells don't work for a variety of reasons, including birth defects, side effects of drugs, exposure to excessively loud sounds or infection by certain viruses.

In a cochlear implant, the microphone, signal processor and transmitter coil worn outside the head send signals to the internal receiver-stimulator, which is implanted in bone under the skin and sends the signals to the electrodes implanted in the cochlea to stimulate auditory nerves. The ear canal, eardrum and hearing bones are bypassed.

The system developed by Young implants all the external components. Sound moves through the ear canal to the eardrum, which vibrates as it does normally. But at the umbo, a sensor known as an accelerometer is attached to detect the vibration. The sensor also is attached to a chip, and together they serve as a microphone that picks up the sound vibrations and converts them into electrical signals sent to the electrodes in the cochlea.

The device still would require patients to wear a charger behind the ear while sleeping at night to recharge an implanted battery. Young says he expects the battery would last one to several days between charging.

Young says the microphone also might be part of an implanted hearing aid that could replace conventional hearing aids for a certain class of patients who have degraded hearing bones unable to adequately convey sounds from conventional hearing aids.

Testing the Microphone in Cadavers

Conventional microphones include a membrane or diaphragm that moves and generates an electrical signal change in response to sound. But they require a hole through which sound must enter – a hole that would get clogged by growing tissue if implanted. So Young's middle-ear microphone instead uses an accelerometer – a 2.5-microgram mass attached to a spring – that would be placed in a sealed package with a low-power silicon chip to convert sound vibrations to outgoing electrical signals.

The package is glued to the umbo so the accelerometer vibrates in response to eardrum vibrations. The moving mass generates an electrical signal that is amplified by the chip, which then connects to the conventional parts of a cochlear implant: a speech processor and stimulator wired to the electrodes in the cochlea.

"Everything is the same as a conventional cochlear implant, except we use an implantable microphone that uses the vibration of the bone," Young says.

To test the new microphone, the researchers used the temporal bones – bones at the side of the skull – and related ear canal, eardrum and hearing bones from four cadaver donors.

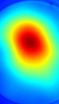

The researchers inserted tubing with a small loudspeaker into the ear canal and generated tones of various frequencies and loudness. As the sounds were picked up by the implanted microphone, the researchers used a laser device to measure the vibrations of the tiny ear bones. They found the umbo – where the eardrum connects to the hammer or malleus – produced the greatest sound vibration, particularly if the incus or anvil bone first was removed surgically.

The experiments showed that when the prototype microphone unit was attached to the umbo, it could pick up medium pitches at conversational volumes, but had trouble detecting quieter, low-frequency sounds. Young plans to improve the microphone to pick up quieter, deeper, very low pitches.

In the tests, the output of the microphone went to speakers; in a real person, it would send sound to the implanted speech processor. To demonstrate the microphone, Young also used it to record the start of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony while implanted in a cadaver ear. It is easily recognizable, even if somewhat fuzzy and muffled.

"The muffling can be filtered out," says Young.

INFORMATION:

To hear a recording of the start of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony through the new microphone implanted in a cadaver's middle-ear, go this link and look near top of the page:

http://unews.utah.edu/news_releases/a-middle-ear-microphone/

University of Utah Public Relations

201 Presidents Circle, Room 308

Salt Lake City, Utah 84112-9017

(801) 581-6773 fax: (801) 585-3350

www.unews.utah.edu

A middle-ear microphone

Device could make cochlear implants more convenient

2012-04-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Yellowstone 'super-eruption' less super, more frequent than thought

2012-04-30

PULLMAN, Wash.— The Yellowstone "super-volcano" is a little less super—but more active—than previously thought.

Researchers at Washington State University and the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre say the biggest Yellowstone eruption, which created the 2 million year old Huckleberry Ridge deposit, was actually two different eruptions at least 6,000 years apart.

Their results paint a new picture of a more active volcano than previously thought and can help recalibrate the likelihood of another big eruption in the future. Before the researchers split ...

Gladstone scientists identify brain circuitry associated with addictive, depressive behaviors

2012-04-30

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—April 29, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have determined how specific circuitry in the brain controls not only body movement but also motivation and learning, providing new insight into neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease—and psychiatric disorders such as addiction and depression.

Previously, researchers in the laboratory of Gladstone Investigator Anatol Kreitzer, PhD, discovered how an imbalance in the activity of a specific category of brain cells is linked to Parkinson's. Now, in a paper published online today in Nature ...

Tablet-based case conferences improve resident learning

2012-04-30

Tablet based conference mirroring is giving residents an up close and personal look at images and making radiology case conferences a more interactive learning experience, a new study shows.

Residents at Northwestern University in Chicago are using tablets and a free screen sharing software during case conferences to see and manipulate the images that are being presented.

"The idea stems from the fact that I was used to having presentation slides directly in front of me during medical school lectures. I thought this would benefit radiology residents, especially in ...

MR enterography is as good or better than standard imaging exams for pediatric Crohn's patients

2012-04-30

MR enterography is superior to CT enterography in diagnosing fibrosis in pediatric patients with Crohn disease and equally as good as CT enterography in detecting active inflammation, and a new study shows.

The study, conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, found that MR enterography was 77.6% accurate in depicting fibrosis compared to 56.9% for CT enterography. MR enterography had an 82.1% accuracy rate versus 77.6% accuracy rate for CT enterography for detecting active inflammation, said Keith Quencer, MD, one of the authors of the study. The study ...

Radiologists rank themselves as less than competent on health policy issues

2012-04-30

Radiologists classify themselves as less competent than other physicians regarding knowledge of patient imaging costs and patient safety, a new study shows.

The study conducted at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia and Northwestern University in Chicago compared 711 radiologists to 2,685 non-radiology physicians. "On a scale of one to five, with five being highly competent, understanding of patient safety was rated as 3.1 by radiologists and 3.33 by non-radiologists," said Rajni Natesan, MD, an author of the study from Northwestern University. Patient imaging ...

Study examines benefit of follow-up CT when abdominal ultrasound inconclusive

2012-04-30

About one-third of CT examinations performed following an inconclusive abdominal ultrasound examination have positive findings, according to a study of 449 patients at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Opinions vary as to the need and relevance for further diagnostic imaging workup after an inconclusive abdominal ultrasound examination, said Supriya Gupta, MD, one of the authors of the study. "Our study found that 32.9% of follow-up CT examinations had positive findings, while 42.7% had findings that were not significant and 11.7% were equivocal. The remaining ...

Researchers question pulling plug on pacifiers

2012-04-30

BOSTON – Binkies, corks, soothers. Whatever you call pacifiers, conventional wisdom holds that giving them to newborns can interfere with breastfeeding.

New research, however, challenges that assertion. In fact, limiting the use of pacifiers in newborn nurseries may actually increase infants' consumption of formula during the birth hospitalization, according to a study to be presented Monday, April 30, at the Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS) annual meeting in Boston.

Studies have shown that breastfed infants have fewer illnesses such as ear infections and diarrhea ...

One-third of adult Americans with arthritis battle anxiety or depression

2012-04-30

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that one-third of U.S. adults with arthritis, 45 years and older, report having anxiety or depression. According to findings that appear today in Arthritis Care & Research, a journal published by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), anxiety is nearly twice as common as depression among people with arthritis, despite more clinical focus on the latter mental health condition.

In the U.S. 27 million individuals, 25 years of age and older, have doctor diagnosed ...

Starting a family does not encourage parents to eat healthier

2012-04-30

Philadelphia, PA, April 30, 2012 – It is often thought that starting a family will lead parents to healthier eating habits, as they try to set a good example for their children. Few studies, however, have evaluated how the addition of children into the home may affect parents' eating habits. Changes in family finances, the challenges of juggling schedules, or a child's eating preferences may influence how a family eats. In one of the first longitudinal studies to examine the effect of having children on parents' eating habits, researchers have found that parenthood does ...

Attosecond lighthouses may help illuminate the tempestuous sea of electrons

2012-04-30

WASHINGTON, April 30--Physicists have long chased an elusive goal: the ability to "freeze" and then study the motion of electrons in matter. Such experiments could help confirm theories of electron motion and yield insights into how and why chemical reactions take place. Now a collaboration of scientists from France and Canada has developed an elegant new method to study electrons' fleeting antics using isolated, precisely timed, and incredibly fast pulses of light. The team will describe the technique at the Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics , taking place in San ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

First evidence of WHO ‘critical priority’ fungal pathogen becoming more deadly when co-infected with tuberculosis

World-first safety guide for public use of AI health chatbots

Women may face heart attack risk with a lower plaque level than men

Proximity to nuclear power plants associated with increased cancer mortality

Women’s risk of major cardiac events emerges at lower coronary plaque burden compared to men

Peatland lakes in the Congo Basin release carbon that is thousands of years old

Breadcrumbs lead to fossil free production of everyday goods

New computation method for climate extremes: Researchers at the University of Graz reveal tenfold increase of heat over Europe

Does mental health affect mortality risk in adults with cancer?

EANM launches new award to accelerate alpha radioligand therapy research

Globe-trotting ancient ‘sea-salamander’ fossils rediscovered from Australia’s dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

[Press-News.org] A middle-ear microphoneDevice could make cochlear implants more convenient