(Press-News.org) Scientists have predicted that ocean temperatures will rise in the equatorial Pacific by the end of the century, wreaking havoc on coral reef ecosystems. But a new study shows that climate change could cause ocean currents to operate in a surprising way and mitigate the warming near a handful of islands right on the equator. As a result these Pacific islands may become isolated refuges for corals and fish.

Here's how it would happen, according to the study by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution scientists Kristopher Karnauskas and Anne Cohen, published April 29 in the journal Nature Climate Change.

At the equator, trade winds push a surface current from east to west. About 100 to 200 meters below, a swift countercurrent develops, flowing in the opposite direction. This, the Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC), is cooler and rich in nutrients. When it hits an island, like a rock in a river, water is deflected upward on the island's western flank and around the islands. This well-known upwelling process brings cooler water and nutrients to the sunlit surface, creating localized areas where tiny marine plants and corals flourish.

On color-enhanced satellite maps showing measurements of global ocean chlorophyll levels, these productive patches of ocean stand out as bright green or red spots, for example around the Galapagos Islands in the eastern Pacific.

But as you look west, chlorophyll levels fade like a comet tail, giving scientists little reason to look closely at scattered low-lying coral atolls farther west. The islands are easy to overlook because they are tiny, remote, and lie at the far left edge of standard global satellite maps that place continents in the center.

Karnauskas, a climate scientist, was working with WHOI coral scientist Anne Cohen to explore how climate change would affect central equatorial Pacific reefs.

When he changed the map view on his screen in order to see the entire tropical Pacific at once, he saw that chlorophyll concentrations jumped up again exactly at the Gilbert Islands on the equator. Satellite maps also showed cooler sea surface temperatures on the west sides of these islands, part of the nation of Kiribati.

"I've been studying the tropical Pacific Ocean for most of my career, and I had never noticed that," he said. "It jumped out at me immediately, and I thought, 'there's probably a story there.' "

So Karnauskas and Cohen began to investigate how the EUC would affect the equatorial islands' reef ecosystems, starting with global climate models that simulate impacts in a warming world.

Global-scale climate models predict that ocean temperatures will rise nearly 3oC (5.4oF) in the central tropical Pacific. Warmer waters often cause corals to bleach, a process in which they lose the tiny symbiotic algae that life in them and provide them with vital nutrition. Bleaching has been a major cause of coral mortality and loss of coral reef area during the last 30 years.

But even the best global models, with their planet-scale views and lower resolution, cannot predict conditions in areas as small as small islands, Karnauskas said.

So they combined global models with a fine-scale regional model to focus on much smaller areas around minuscule islands scattered along the equator. To accommodate the trillions of calculations needed for such small-area resolution, they used the new high-performance computer cluster at WHOI called "Scylla."

"Global models predict significant temperature increase in the central tropical Pacific over the next few decades, but in truth conditions can be highly variable across and around a coral reef island," Cohen said. "To predict what the coral reef will experience under global climate change, we have to use high-resolution models, not global models."

Their model predicts that as air temperatures rise and equatorial trade winds weaken, the Pacific surface current will also weaken by 15 percent by the end of the century. The then-weaker surface current will impose less friction and drag on the EUC, so this deeper current will strengthen by 14 percent.

"Our model suggests that the amount of upwelling will actually increase by about 50 percent around these islands and reduce the rate of warming waters around them by about 0.7oC (1.25oF) per century," Karnauskas said.

A handful of coral atolls on the equator, some as small as 4 square kilometers (1.54 square miles) in area, may not seem like much. But Karnauskas's and Cohen's results say waters on the western sides of the islands will warm more slowly than at islands 2 degrees (or 138 miles) north and south of the equator that are not in the way of the EUC. That gives the Gilbert Islands a significant advantage over neighboring reef systems, they said.

"While the mitigating effect of a strengthened Equatorial Undercurrent will not spare the corals the perhaps-inevitable warming expected for this region, the warming rate will be slower around these equatorial islands, which may allow corals and their symbiotic algae a better chance to adapt and survive," Karnauskas said. If the model holds true, then even if neighboring reefs are hard hit, equatorial island coral reefs may well survive to produce larvae of corals and other reef species. Like a seed bank for the future, they might be a source of new corals and other species that could re-colonize damaged reefs.

"The globe is warming, but there are things going on underfoot that will slow that warming for certain parts of certain coral reef islands," said Cohen.

"These little islands in the middle of the ocean can counteract global trends and have a big impact on their own future, which I think is a beautiful concept," Karnauskas said.

"The finding that there may be refuges in the tropics where local circulation features buffer the trend of rising sea surface temperature has important implications for the survival of coral reef systems," said David Garrison, program director in the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the research.

INFORMATION:

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the oceans' role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu.

END

Why do some teenagers start smoking or experimenting with drugs—while others don't?

In the largest imaging study of the human brain ever conducted—involving 1,896 14-year-olds—scientists have discovered a number of previously unknown networks that go a long way toward an answer.

Robert Whelan and Hugh Garavan of the University of Vermont, along with a large group of international colleagues, report that differences in these networks provide strong evidence that some teenagers are at higher risk for drug and alcohol experimentation—simply because their brains work differently, ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Red, green, and blue lasers have become small and cheap enough to find their way into products ranging from BluRay DVD players to fancy pens, but each color is made with different semiconductor materials and by elaborate crystal growth processes. A new prototype technology demonstrates all three of those colors coming from one material. That could open the door to making products, such as high-performance digital displays, that employ a variety of laser colors all at once.

"Today in order to create a laser display with arbitrary colors, ...

A combination of two diabetes drugs, metformin and rosiglitazone, was more effective in treating youth with recent-onset type 2 diabetes than metformin alone, a study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has found. Adding an intensive lifestyle intervention to metformin provided no more benefit than metformin therapy alone.

The study also found that metformin therapy alone was not an effective treatment for many of these youth. In fact, metformin had a much higher failure rate in study participants than has been reported in studies of adults treated with ...

It is important to be able to monitor genetically modified (GM) crops, not only in the field but also during the food processing chain. New research published in BioMed Central's open access journal BMC Biotechnology shows that products from genetically modified crops can be identified at low concentration, using bioluminescent real time reporter (BART) technology and loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). The combination of these techniques was able to recognise 0.1% GM contamination of maize, far below the current EU limit of 0.9%.

In agriculture GM crops have ...

Alu elements infiltrated the ancestral primate genome about 65 million years ago. Once gained an Alu element is rarely lost so comparison of Alu between species can be used to map primate evolution and diversity. New research published in BioMed Central's open access journal Mobile DNA has found a single Alu, which appears to be an ancestral great ape Alu, that has uniquely multiplied within the orangutan genome.

Analysis of DNA sequences has found over a million Alu elements within each primate genome, many of which are species specific: 5,000 are unique to humans, ...

Early colonization of the gut by microbes in infants is critical for development of their intestinal tract and in immune development. A new study, published in BioMed Central's open access journal Genome Biology, shows that differences in bacterial colonization of formula-fed and breast-fed babies leads to changes in the infant's expression of genes involved in the immune system, and in defense against pathogens.

The health of individuals can be influenced by the diversity of microbes colonizing the gut, and microbial colonization can be especially important in regulating ...

SALT LAKE CITY, April 30, 2012 – Cochlear implants have restored basic hearing to some 220,000 deaf people, yet a microphone and related electronics must be worn outside the head, raising reliability issues, preventing patients from swimming and creating social stigma.

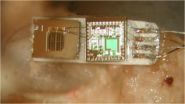

Now, a University of Utah engineer and colleagues in Ohio have developed a tiny prototype microphone that can be implanted in the middle ear to avoid such problems.

The proof-of-concept device has been successfully tested in the ear canals of four cadavers, the researchers report in a study just published ...

PULLMAN, Wash.— The Yellowstone "super-volcano" is a little less super—but more active—than previously thought.

Researchers at Washington State University and the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre say the biggest Yellowstone eruption, which created the 2 million year old Huckleberry Ridge deposit, was actually two different eruptions at least 6,000 years apart.

Their results paint a new picture of a more active volcano than previously thought and can help recalibrate the likelihood of another big eruption in the future. Before the researchers split ...

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—April 29, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have determined how specific circuitry in the brain controls not only body movement but also motivation and learning, providing new insight into neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease—and psychiatric disorders such as addiction and depression.

Previously, researchers in the laboratory of Gladstone Investigator Anatol Kreitzer, PhD, discovered how an imbalance in the activity of a specific category of brain cells is linked to Parkinson's. Now, in a paper published online today in Nature ...

Tablet based conference mirroring is giving residents an up close and personal look at images and making radiology case conferences a more interactive learning experience, a new study shows.

Residents at Northwestern University in Chicago are using tablets and a free screen sharing software during case conferences to see and manipulate the images that are being presented.

"The idea stems from the fact that I was used to having presentation slides directly in front of me during medical school lectures. I thought this would benefit radiology residents, especially in ...