(Press-News.org) The fungal infection that killed a record number of amphibians worldwide leads to deadly dehydration in frogs in the wild, according to results of a new study.

High levels of an aquatic, chytrid fungus called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) disrupt fluid and electrolyte balance in wild frogs, the scientists say, severely depleting the frogs' sodium and potassium levels and causing cardiac arrest and death.

Their findings confirm what researchers have seen in carefully controlled lab experiments with the fungus, but San Francisco State University biologist Vance Vredenburg said the data from wild frogs provide a much better idea of how the disease progresses.

"The mode of death discovered in the lab seems to be what's actually happening in the field," he said, "and it's that understanding that is key to doing something about it in the future."

Results of the study are published today in the journal PLoS ONE.

"Wildlife diseases can be just as devastating to our health and economy as agricultural and human diseases," said Sam Scheiner, NSF program officer for the joint National Science Foundation-National Institutes of Health Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases program, which funded the research.

At NSF, the Directorates for Biological Sciences and Geosciences support the program.

"Bd has been decimating frog and salamander species worldwide, which may fundamentally disrupt natural systems," said Scheiner. "This study is an important advance in our understanding of the disease--a first step in finding a way to reduce its effects."

At the heart of the new study are blood samples drawn from mountain yellow-legged frogs by Vredenburg and colleagues in 2004, as the chytrid epidemic swept through California's Sierra Nevada mountains.

"It's really rare to be able to study physiology in the wild like this, at the exact moment of a disease outbreak," said University of California, Berkeley ecologist Jamie Voyles, the lead author of the paper.

Unfortunately, it is a study that can't be duplicated--at least not in the Sierra Nevada.

Frog populations there have been devastated by chytrid, declining by 95 percent after the fungus was first detected in 2004.

"It's been really sad to walk around the basins and think, 'wow, they're really all gone,'" Vredenburg said.

The chytrid fungus attacks an amphibian's skin, causing it to become up to 40 times thicker in some instances.

Since frogs depend on their skin to absorb water and essential electrolytes like sodium from their environment, Voyles and her colleagues knew that the fungus would disrupt fluid balances in the infected amphibians.

But they were surprised to find that electrolyte levels were much lower than anticipated. "It's clear that this fungus has a profound effect in the wild," Voyles said.

Scientists want to learn as much as they can about how the fungus affects wild amphibians, with the hope that these findings will lead to better treatments for the infection.

"The chytrid fungus is causing these frogs to become severely dehydrated, even though they are literally surrounded by water," said Cheryl Briggs, a University of California, Santa Barbara biologist and co-author of the paper.

The new study suggests that individual frogs being treated for the infection might benefit from having electrolyte supplementation in the advanced stages of the disease.

Researchers like Vredenburg already are experimenting with different ways of treating individual frogs, such as applying antifungal therapies or inoculating the frogs with "probiotic" bacteria that produce a compound that kills the fungus.

"The disease is not very hard to treat in the lab with antifungals," Vredenburg said. "But in nature, the disease is still a moving target."

It is still unclear exactly how chytrid spreads across a region, and which frogs might be susceptible to re-infection after treatment.

Earlier this year, Vredenburg and colleagues showed that a common North American frog might be an important carrier of the infection.

The chytrid fungus has killed off more than 200 amphibian species across the globe, but Voyles said the research offers "a glimmer of hope that it might be possible to do something to mitigate the loss."

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors of the paper are Tate Tunstall and Erica Bree Rosenblum of UC Berkeley, and John Parker of University of California, San Francisco.

Blood samples show deadly frog fungus at work in the wild

Pathogen leads to dehydration, other ill effects

2012-04-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Can nature's beauty lift citizens from poverty?

2012-04-30

Using nature's beauty as a tourist draw can boost conservation in China's valued panda preserves, but it isn't an automatic ticket out of poverty for the humans who live there, a unique long-term study shows.

Often those who benefit most from nature-based tourism are people who already have resources. The truly impoverished have a harder time breaking into the tourism business, according to the paper, "Drivers and Socioeconomic Impacts of Tourism Participation in Protected Areas," published in the April 25 edition of PLoS One.

The study looks at nearly a decade of burgeoning ...

Folding light: Wrinkles and twists boost power from solar panels

2012-04-30

Taking their cue from the humble leaf, researchers have used microscopic folds on the surface of photovoltaic material to significantly increase the power output of flexible, low-cost solar cells.

The team, led by scientists from Princeton University, reported online April 22 in the journal Nature Photonics that the folds resulted in a 47 percent increase in electricity generation. Yueh-Lin (Lynn) Loo, the principal investigator, said the finely calibrated folds on the surface of the panels channel light waves and increase the photovoltaic material's exposure to light.

"On ...

NYUCN's Dr. Laura Wagner: Study finds accreditation improves safety culture at nursing homes

2012-04-30

Accredited nursing homes report a stronger resident safety culture than nonaccredited facilities, according to a new study published in the May 2012 issue of The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

The study shows that senior managers at more than 4,000 facilities across the U.S. identify Joint Commission accreditation as a positive influence on patient safety issues such as staffing, teamwork, training, nonpunitive responses to mistakes, and communication openness. The findings that accreditation stimulates positive changes in safety-related organizational ...

Slow-growing babies more likely in normal-weight women; Less common in obese pregnancies

2012-04-30

Obesity during pregnancy puts women at higher risk of a multitude of challenges. But, according to a new study presented earlier this month at the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine annual convention, fetal growth restriction, or the poor growth of a baby while in the mother's womb, is not one of them. In fact, study authors from the University of Rochester Medical Center found that the incidence of fetal growth restriction was lower in obese women when compared to non-obese women.

Researchers, led by senior study author and high-risk pregnancy expert Loralei ...

Assembly errors quickly identified

2012-04-30

Today's cars are increasingly custom-built. One customer might want electric windows, heated door mirrors and steering-wheel-mounted stereo controls, while another is satisfied with the minimum basic equipment. The situation with aircraft is no different: each airline is looking for different interior finishes – and lighting, ventilation, seating and monitors are different from one company to the next. Yet the customer's freedom is the manufacturer's challenge: because individual parts and mountings have to be installed in different locations along the fuselage, automated ...

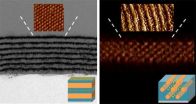

Golden potential for gold thin films

2012-04-30

Scientists with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley have directed the first self-assembly of nanoparticles into device-ready materials. Through a relatively easy and inexpensive technique based on blending nanoparticles with block co-polymer supramolecules, the researchers produced multiple-layers of thin films from highly ordered one-, two- and three-dimensional arrays of gold nanoparticles. Thin films such as these have potential applications for a wide range of fields, including computer memory storage, ...

New graphene-based material could revolutionize electronics industry

2012-04-30

The most transparent, lightweight and flexible material ever for conducting electricity has been invented by a team from the University of Exeter. Called GraphExeter, the material could revolutionise the creation of wearable electronic devices, such as clothing containing computers, phones and MP3 players.

GraphExeter could also be used for the creation of 'smart' mirrors or windows, with computerised interactive features. Since this material is also transparent over a wide light spectrum, it could enhance by more than 30% the efficiency of solar panels.

Adapted from ...

lobSTR algorithm rolls DNA fingerprinting into 21st century

2012-04-30

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (April 27, 2012) – As any crime show buff can tell you, DNA evidence identifies a victim's remains, fingers the guilty, and sets the innocent free. But in reality, the processing of forensic DNA evidence takes much longer than a 60-minute primetime slot.

To create a victim or perpetrator's DNA profile, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) scans a DNA sample for at least 13 short tandem repeats (STRs). STRs are collections of repeated two to six nucleotide-long sequences, such as CTGCTGCTG, which are scattered around the genome. Because the ...

New avocado rootstocks are high-performing and disease-tolerant

2012-04-30

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Avocado, a significant fruit crop grown in many tropical and subtropical parts of the world, is threatened by Phytophthora root rot (PRR), a disease that has already eliminated commercial avocado production in many areas in Latin America and crippled production in Australia and South Africa. Just in California the disease is estimated to cost avocado growers approximately $30-40 million a year in production losses.

Research on developing PRR-tolerant rootstocks to manage the disease has been a major focus of avocado research at the University of California, ...

Big girls don't cry

2012-04-30

A study to be published in the June 2012 issue of Journal of Adolescent Health looking at the relationships between body satisfaction and healthy psychological functioning in overweight adolescents has found that young women who are happy with the size and shape of their bodies report higher levels of self-esteem. They may also be protected against the negative behavioral and psychological factors sometimes associated with being overweight.

A group of 103 overweight adolescents were surveyed between 2004 and 2006, assessing body satisfaction, weight-control behavior, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

Power grids to epidemics: study shows small patterns trigger systemic failures

Computational insights into the interactions of andrographolide derivative SRJ09 with histone deacetylase for the management of beta thalassemia

A genetic brake that forms our muscles

CHEST announces first class of certified critical care advanced practice providers awarded CCAPP Designation

Jeonbuk National University researchers develop an innovative prussian-blue based electrode for effective and efficient cesium removal

Self-organization of cell-sized chiral rotating actin rings driven by a chiral myosin

Report: US history polarizes generations, but has potential to unite

Tiny bubbles, big breakthrough: Cracking cancer’s “fortress”

A biological material that becomes stronger when wet could replace plastics

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Get the picture? High-tech, low-cost lens focuses on global consumer markets

Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne bacteria remains a public health concern in Europe

Safer batteries for storing energy at massive scale

How can you rescue a “kidnapped” robot? A new AI system helps the robot regain its sense of location in dynamic, ever-changing environments

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

[Press-News.org] Blood samples show deadly frog fungus at work in the wildPathogen leads to dehydration, other ill effects