(Press-News.org) Research from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that the human olfactory bulb – a structure in the brain that processes sensory input from the nose – differs from that of other mammals in that no new neurons are formed in this area after birth. The discovery, which is published in the scientific journal Neuron, is based on the age-determination of the cells using the carbon-14 method, and might explain why the human sense of smell is normally much worse than that of other animals.

"I've never been so astonished by a scientific discovery," says lead investigator Jonas Frisén, Tobias Foundation Professor of stem cell research at Karolinska Institutet. "What you would normally expect is for humans to be like other animals, particularly apes, in this respect."

It was long thought that all brain neurons were formed up to the time of birth, after which production stopped. A paradigm shift occurred when scientists found that nerve cells were being continually formed from stem cells in the mammalian brain, which changed scientific views on the plasticity of the brain and raised hopes of being able to replace neurons lost during some types of neurological disease.

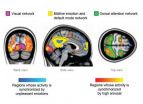

In the adult mammal, new nerve cells are formed in two regions of the brain: the hippocampus and the olfactory bulb. While the former has an important part to play in memory, the latter is essential to the interpretation of smells. However, owing to the difficulty of studying the formation of new neurons in humans, the extent to which this phenomenon also occurs in the human brain has remained unclear. In this present study, researchers at Karolinska Institutet and their Austrian and French colleagues made use of the sharp rise in atmospheric carbon-14 caused by Cold War nuclear tests to find an answer to this question.

Carbon-14 is incorporated in DNA, making it possible to gauge the age of the cells by measuring how much of the isotope they contain. Doing this, the team found that the olfactory bulb neurons in their adult human subjects had carbon-14 levels that matched those at the atmosphere at the time of their birth. This is a strong indication that there is no significant generation of new neurons in this part of the brain, something that sets humans apart from all other mammals.

"Humans are less dependent on their sense of smell for their survival than many other animals, which may be related to the loss of new cell generation in the olfactory bulb, but this is just speculation," continues Professor Frisén.

Professor Frisén and his team now plan to study the extent of neuron generation in the hippocampus, a part of the brain that is important for higher cerebral functions in humans. This present study was made possible by support from the Tobias Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF), the American Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation (NARSAD), the Swedish Brain Fund, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, AFA Försäkring, the EU and the Stockholm County Council through its ALF agreement with Karolinska Institutet.

###Publication: "The age of olfactory bulb neurons in humans", Olaf Bergmann, Jakob Liebl, Samuel Bernard, Kanar Alkass, Maggie S.Y. Yeung, Peter Steier, Walter Kutschera, Lars Johnson, Mikael Landén, Henrik Druid, Kirsty L. Spalding & Jonas Frisén, Neuron, print issue 24 May 2012.

Journal website: http://www.cell.com/neuron/

For further information, please contact:

Jonas Frisén, Professor

Department of Cell and Molecular Biology

Tel: +46 (0)8-524 875 62

Email: jonas.frisen@ki.se

Kirsty Spalding, Assistant Professor

Department of Cell and Molecular Biology

Tel: +46 (0)8-524 87464 or +46 (0)70-437 15 42

Email: kirsty.spalding@ki.se

Contact the press office and download photos: http://ki.se/pressroom

Karolinska Institutet is one of the world's leading medical universities. It accounts for over 40 per cent of the medical academic research conducted in Sweden and offers the country's broadest range of education in medicine and health sciences. Since 1901 the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet has selected the Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine.

No new neurons in the human olfactory bulb

Findings astonish scientists

2012-05-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Gene discovery points towards new type of male contraceptive

2012-05-28

A new type of male contraceptive could be created thanks to the discovery of a key gene essential for sperm development.

The finding could lead to alternatives to conventional male contraceptives that rely on disrupting the production of hormones, such as testosterone and can cause side-effects such as irritability, mood swings and acne.

Research, led by the University of Edinburgh, has shown how a gene – Katnal1 – is critical to enable sperm to mature in the testes.

If scientists can regulate the Katnal1 gene in the testes, they could prevent sperm from maturing ...

Drug allergy discovery

2012-05-28

A research team led by the University of Melbourne and Monash University, Australia, has discovered why people can develop life-threatening allergies after receiving treatment for conditions such as epilepsy and AIDS.

The finding could lead to the development of a diagnostic test to determine drug hypersensitivity.

The study published today in the journal Nature, revealed how some drugs inadvertently target the immune system to alter how the body's immune system perceives it's own tissues, making them look foreign.

The immune system then attacks the foreign nature ...

Beetle-infested pine trees contribute to air pollution and haze in forests

2012-05-28

The hordes of bark beetles that have bored their way through more than six billion trees in the western United States and British Columbia since the 1990s do more than kill stately pine, spruce and other trees.

Results of a new study show that these pests can make trees release up to 20 times more of the organic substances that foster haze and air pollution in forested areas.

A paper reporting the findings appears today in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, published by the American Chemical Society.

Scientists Kara Huff Hartz of Southern Illinois University ...

Feeling strong emotions makes peoples' brains 'tick together'

2012-05-28

Experiencing strong emotions synchronises brain activity across individuals, research team at Aalto University and Turku PET Centre in Finland has revealed.

Human emotions are highly contagious. Seeing others' emotional expressions such as smiles triggers often the corresponding emotional response in the observer. Such synchronisation of emotional states across individuals may support social interaction: When all group members share a common emotional state, their brains and bodies process the environment in a similar fashion.

Researchers at Aalto University and ...

Dramatic increase in fragility fractures expected in Latin America

2012-05-28

The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), in cooperation with medical and patient societies from throughout Latin America, has today published a landmark report which compiles osteoporosis-related data on 14 countries and the region as a whole. The report shows that fragility fractures due to osteoporosis are predicted to more than double in some countries in the coming decades.

Osteoporosis, which literally means 'porous bones', is a disease which causes bones to become fragile and more likely to break. Older adults, and post-menopausal women in particular, are ...

In Brazil number of hip fractures expected to increase 32 percent by 2050

2012-05-28

A new Audit report on fragility fractures, issued today by the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), predicts that Brazil will experience an explosion in the number of fragility fractures due to osteoporosis in the coming decades.

Osteoporosis, a disease which weakens bones and makes them more likely to fracture, is thought to affect around 33% of postmenopausal women in Brazil. Fractures due to osteoporosis mostly affect older adults, with fractures at the spine and hip causing the most suffering, disability and healthcare expenditure.

Currently, about 20% ...

Food, water safety provide new challenges for today's sensors

2012-05-28

Sensors that work flawlessly in laboratory settings may stumble when it comes to performing in real-world conditions, according to researchers at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

These shortcomings are important as they relate to safeguarding the nation's food and water supplies, said Ali Passian, lead author of a Perspective paper published in ACS Nano. In their paper, titled "Critical Issues in Sensor Science to Aid Food and Water Safety," the researchers observe that while sensors are becoming increasingly sophisticated, little or no field ...

Exotic particles, chilled and trapped, form giant matter wave

2012-05-28

Physicists have trapped and cooled exotic particles called excitons so effectively that they condensed and cohered to form a giant matter wave.

This feat will allow scientists to better study the physical properties of excitons, which exist only fleetingly yet offer promising applications as diverse as efficient harvesting of solar energy and ultrafast computing.

"The realization of the exciton condensate in a trap opens the opportunity to study this interesting state. Traps allow control of the condensate, providing a new way to study fundamental properties of light ...

Healing the voice: New American Chemical Society video on synthetic vocal cords

2012-05-28

WASHINGTON, May 24, 2012 — An effort to develop synthetic vocal cords to heal the voices of people with scarred natural vocal tissues is the topic of the latest episode of the American Chemical Society's (ACS') Bytesize Science series. The video is available at www.BytesizeScience.com.

Filmed in the lab of 2012 ACS Priestley Medalist and David H. Koch Institute Professor Robert S. Langer, Ph.D., at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the video highlights the development of a flexible polymer material that mimics the traits of human vocal cords. The video begins ...

London researcher calls for new approach to regulating probiotics

2012-05-28

LONDON, ON – In today's Nature scientific journal Dr. Gregor Reid, Director of the Canadian R&D Centre for Probiotics at Lawson Health Research Institute and a scientist at Western University, calls for a Category Tree system to be implemented in the United States and Europe to better inform consumers about probiotics.

Globally, the market for probiotics (beneficial microorganisms) exceeds $30 billion; however, consumers have little way of knowing which products have been tested in humans and what they do for health. Furthermore, the regulatory system in the US maintains ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Racial/ethnic disparities among people fatally shot by U.S. police vary across state lines

US gender differences in poverty rates may be associated with the varying burden of childcare

3D-printed robotic rattlesnake triggers an avoidance response in zoo animals, especially species which share their distribution with rattlers in nature

Simple ‘cocktail’ of amino acids dramatically boosts power of mRNA therapies and CRISPR gene editing

Johns Hopkins scientists engineer nanoparticles able to seek and destroy diseased immune cells

A hidden immune circuit in the uterus revealed: Findings shed light on preeclampsia and early pregnancy failure

Google Earth’ for human organs made available online

AI assistants can sway writers’ attitudes, even when they’re watching for bias

Still standing but mostly dead: Recovery of dying coral reef in Moorea stalls

3D-printed rattlesnake reveals how the rattle is a warning signal

Despite their contrasting reputations, bonobos and chimpanzees show similar levels of aggression in zoos

Unusual tumor cells may be overlooked factors in advanced breast cancer

Plants pause, play and fast forward growth depending on types of climate stress

University of Minnesota scientists reveal how deadly Marburg virus enters human cells, identify therapeutic vulnerability

Here's why seafarers have little confidence in autonomous ships

MYC amplification in metastatic prostate cancer associated with reduced tumor immunogenicity

The gut can drive age-associated memory loss

Enhancing gut-brain communication reversed cognitive decline, improved memory formation in aging mice

Mothers exposure to microbes protect their newborn babies against infection

How one flu virus can hamper the immune response to another

Researchers uncover distinct tumor “neighborhoods”, with each cell subtype playing a specific role, in aggressive childhood brain cancer

Researchers develop new way to safely insert gene-sized DNA into the genome

Astronomers capture birth of a magnetar, confirming link to some of universe’s brightest exploding stars

New photonic device, developed by MIT researchers, efficiently beams light into free space

UCSB researcher bridges the worlds of general relativity and supernova astrophysics

Global exchange of knowledge and technology to significantly advance reef restoration efforts

Vision sensing for intelligent driving: technical challenges and innovative solutions

To attempt world record, researchers will use their finding that prep phase is most vital to accurate three-point shooting

AI is homogenizing human expression and thought, computer scientists and psychologists say

Severe COVID-19, flu facilitate lung cancer months or years later, new research shows

[Press-News.org] No new neurons in the human olfactory bulbFindings astonish scientists