(Press-News.org) Science has known about plant hormones since Charles Darwin experimented with plant shoots and showed that the shoots bend toward the light as long as their tips, which are secreting a growth hormone, aren't cut off.

But it is only recently that scientists have begun to put a molecular face on the biochemical systems that modulate the levels of plant hormones to defend the plant from herbivore or pathogen attack or to allow it to adjust to changes in temperature, precipitation or soil nutrients.

Now, a cross-Atlantic collaboration between scientists at Washington University in St. Louis, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, both in Grenoble, France, has revealed the workings of a switch that activates plant hormones, tags them for storage or marks them for destruction.

The research appeared online in the May 24 issue of Science Express and will be published in a forthcoming issue of Science.

"The enzymes are cellular stop/go switches that turn hormone responses on and off," says Joseph Jez, PhD, associate professor of biology in Arts & Sciences at WUSTL and senior author on the paper.

The research is relevant not just to design of herbicides — some of which are synthetic plant hormones — but also to the genetic modification of plants to suit more extreme growing conditions due to unchecked climate change.

What plant hormones do

Plants can seem pretty defenseless. After all, they can't run from the weed whacker or move to the shade when they're wilting, and they don't have teeth, claws, nervous systems, immune systems or most of the other protective equipment that comes standard with an animal chassis.

But they do make hormones. Or to be precise — because hormones are often defined as chemicals secreted by glands and plants don't have glands — they make chemicals that in very low concentrations dramatically alter their development, growth or metabolism. In the original sense of the word "hormone," which is Greek for impetus, they stir up the plant.

In plants as in animals, hormones control growth and development. For example, the auxins, one group of plant hormones, trigger cell division, stem elongation and differentiation into roots, shoots and leaves. The herbicide 2,4-D is a synthetic auxin that kills broadleaf plants, such as dandelions or pigweed, by forcing them to grow to the point of exhaustion.

Asked for his favorite example of a plant hormone, Corey S. Westfall brings up its chemical defense systems. Westfall, a graduate student in the Jez laboratory, who together with Chloe Zubieta, PhD, a staff scientist at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility did most of the work on the research.

Walking through a public park in St. Louis near WUSTL, Westfall often sees oak leaves with brown spots on them. The spots are cells that have deliberately committed cell suicide to deny water and nutrients to a pathogen that landed in the center of the spot. This form of self-sterilization is triggered by the plant hormone salicylic acid.

Westfall also mentions the jasmonates, which cause plants to secrete compounds such as tannins that discourage herbivores. Tannins are toxic to insects because they bind to salivary proteins and inactivate them. So insects that ingest lots of tannins fail to gain weight and may eventually die.

A little more, a little less

Hormones, in other words, allow plants to respond quickly and sometimes dramatically to developmental cues and environmental stresses. But in order to respond appropriately, plants have to be able to sensitively control the level and activity of the hormone molecules.

The Science paper reveals a key control mechanism: a family of enzymes that attach amino acids to hormone molecules to turn the hormones on or off. Depending on the hormone and the amino acid, the reaction can activate the hormone, put it in storage or mark it for destruction.

For example, in the model plant, thale cress, fewer than 5 percent of the auxins are found in the active free-form. Most are conjugated (attached) to amino acids and inactive, constituting a pool of molecules that can be quickly converted to the active free form.

The attachment of amino acids is catalyzed by a large family of enzymes (proteins) called the GH3s, which probably originated 400 million years ago, before the evolution of land plants. The genes diversified over time: there are only a few in mosses, but 19 in thale cress and more than 100 in total.

"Nature finds things that works and sticks with them," Jez says. The GH3s, he says, are a remarkable example of gene family expansion to suit multiple purposes.

A swiveling hormone modification machine

The first GH3 gene — from soybean — was sequenced in 1984. But gene (or protein) sequences reveal little about what proteins do and how they do it. To understand function, the scientists had to figure out how these enzymes, which start out as long necklaces of amino acids, fold into knobbly globules with protective indentations for chemical reactions.

Unfortunately, protein folding is a notoriously hard problem, one as yet beyond the reach of computer calculations at least as a matter of routine. So most protein structures are still solved by the time-intensive process of crystallizing the protein and bombarding the crystal with X-rays to locate the atoms within it. Both the Jez lab and the Structural Biology Group at European Synchrotron Radiation Facility specialize in protein crystallization.

By good fortune, the scientists were able to freeze the enzymes in two different conformations. This information and that gleaned by mutating the amino acids lining the enzyme's active site let them piece together what the enzymes were doing.

It turned out that the GH3 enzymes, which fold into a shape called a hammer and anvil, cataylze a two-step chemical reaction. In the first step, the enzyme's active site is open allowing ATP (adenosine triphosphate, the cell's energy storage molecule) and the free acid form of the plant hormone to enter.

Once the molecules are bound, the enzyme strips phosphate groups off the ATP molecule to form AMP and sticks the AMP onto an "activated" form of the hormone, a reaction called adenylation.

Adenylation triggers part of the enzyme to rotate over the active site, preparing it to catalyze the second reaction, in which an amino acid is snapped onto the hormone molecule. This is called a transferase reaction.

"After you pop off the two phosphates," Jez says, "the top of the molecule ratchets in and sets up a completely different active site. We were lucky enough to capture that crystallographically because we caught the enzyme in both positions."

The same basic two-step reaction can either activate or inactivate a hormone molecule. Addition of the amino acid isoleucine to a jasmonate, for example, makes the jasmonate hormone bioactive. On the other hand addition of the amino acid aspartate to the auxin known as IAA marks it for destruction.

This is the first time any GH3 structure has been solved.

Plant breeding in a hurry

Understanding the powerful plant hormone systems will give scientists a much faster and more targeted way to breed and domesticate plant species, speed that will be needed to keep up with the rapid shift of plant growing zones.

Plant hormones, like animal hormones, typically affect the transcription of many genes and so have multiple effects, some desirable and others undesirable. But GH3 mutants provide a tantalizing glimpse of what might be possible: some are resistant to bacterial pathogens, others to fungal pathogens and some are exceptionally drought tolerant.

Westfall mentions that in 2003, a scientist at Purdue University figured out that a corn strain that had a short stalk but normal ears and tassels had a mutation that interferes with the flow of the hormone auxin in the plant.

Because the plants are so much smaller, they are relatively drought resistant and might be able to grow in India, where North American corn varieties cannot survive. Similar high-yield dwarf varieties might prevent famine in areas of the world where many people are at risk of starvation.

INFORMATION:

Key part of plants' rapid response system revealed

International collaboration puts molecular face on enzyme family that allows plants to adjust quickly to changing conditions

2012-06-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Peaches, plums, nectarines give obesity, diabetes slim chance

2012-06-19

COLLEGE STATION – Peaches, plums and nectarines have bioactive compounds that can potentially fight-off obesity-related diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to new studies by Texas AgriLife Research.

The study, which will be presented at the American Chemical Society in Philadelphia next August, showed that the compounds in stone fruits could be a weapon against "metabolic syndrome," in which obesity and inflammation lead to serious health issues, according to Dr. Luis Cisneros-Zevallos, AgriLife Research food scientist.

"In recent years obesity ...

Device implanted in brain has therapeutic potential for Huntington's disease

2012-06-19

Amsterdam, NL, June 18, 2012 – Studies suggest that neurotrophic factors, which play a role in the development and survival of neurons, have significant therapeutic and restorative potential for neurologic diseases such as Huntington's disease. However, clinical applications are limited because these proteins cannot easily cross the blood brain barrier, have a short half-life, and cause serious side effects. Now, a group of scientists has successfully treated neurological symptoms in laboratory rats by implanting a device to deliver a genetically engineered neurotrophic ...

Link between vitamin C and twins can increase seed production in crops

2012-06-19

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Biochemists at the University of California, Riverside report a new role for vitamin C in plants: promoting the production of twins and even triplets in plant seeds.

Daniel R. Gallie, a professor of biochemistry, and Zhong Chen, an associate research biochemist in the Department of Biochemistry, found that increasing the level of dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), a naturally occurring enzyme that recycles vitamin C in plants and animals, increases the level of the vitamin and results in the production of twin and triplet seedlings in a single seed.

The ...

Research breakthrough: High brain integration underlies winning performances

2012-06-19

Scientists trying to understand why some people excel — whether as world-class athletes, virtuoso musicians, or top CEOs — have discovered that these outstanding performers have unique brain characteristics that make them different from other people.

A study published in May in the journal Cognitive Processing found that 20 top-level managers scored higher on three measures — the Brain Integration Scale, Gibbs's Socio-moral Reasoning questionnaire, and an inventory of peak experiences — compared to 20 low-level managers that served as matched controls. This is the fourth ...

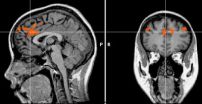

This is your brain on no self-control

2012-06-19

New pictures from the University of Iowa show what it looks like when a person runs out of patience and loses self-control.

A study by University of Iowa neuroscientist and neuro-marketing expert William Hedgcock confirms previous studies that show self-control is a finite commodity that is depleted by use. Once the pool has dried up, we're less likely to keep our cool the next time we're faced with a situation that requires self-control.

But Hedgcock's study is the first to actually show it happening in the brain using fMRI images that scan people as they perform self-control ...

Million year old groundwater in Maryland water supply

2012-06-19

A portion of the groundwater in the upper Patapsco aquifer underlying Maryland is over a million years old. A new study suggests that this ancient groundwater, a vital source of freshwater supplies for the region east of Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, was recharged over periods of time much greater than human timescales.

"Understanding the average age of groundwater allows scientists to estimate at what rate water is re-entering the aquifer to replace the water we are currently extracting for human use," explained USGS Director Marcia McNutt. "This is the first step ...

Anti-cocaine vaccine described in Human Gene Therapy Journal

2012-06-19

New Rochelle, NY, June 18, 2012—A single-dose vaccine capable of providing immunity against the effects of cocaine offers a novel and groundbreaking strategy for treating cocaine addiction is described in an article published Instant Online in Human Gene Therapy, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. (http://www.liebertpub.com) The article is available free online at the Human Gene Therapy website (http://www.liebertpub.com/hum).

"This is a very novel approach for addressing the huge medical problem of cocaine addiction," says James M. Wilson, MD, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, ...

Doctors cite concern for patients, colleagues top motives for working sick

2012-06-19

An unwavering work ethic is a hallmark of many health professionals. But a new survey finds that when a doctor is sick, staunch dedication can have unintended consequences.

A poll of 150 attendees of an American College of Physicians meeting in 2010 revealed that more than half of resident physicians had worked with flu-like symptoms at least once in the last year. One in six reported working sick on three or more occasions during the year, according to the survey conducted by researchers at the University of Chicago Medicine and Massachusetts General Hospital. Notably, ...

Canadian teen moms run higher risk of abuse, depression than older mothers

2012-06-19

(Edmonton) Teen mothers are far more likely to suffer abuse and postpartum depression than older moms, according to a study of Canadian women's maternity experiences by a University of Alberta researcher.

Dawn Kingston, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Nursing, analyzed data from the Maternity Experiences Survey, which asked more than 6,400 new mothers about their experiences with stress, violence, pre- and postnatal care, breastfeeding and risky behaviour like smoking and drug use before, during and after pregnancy.

Kingston said the survey offers the first ...

Understanding faults and volcanics, plus life inside a rock

2012-06-19

Boulder, Colo., USA – This posting: Orange-like rocks in Utah with iron-oxide rinds and fossilized bacteria inside that are believed to have eaten the interior rock material, plus noted similarities to "bacterial meal" ingredients and rock types on Mars; fine-tuning the prediction of volcanic hazards and warning systems for both high population zones and at Tristan da Cunha, home to the most remote population on Earth; news from SAFOD; and discovery in Germany of the world's oldest known mosses.

Biosignatures link microorganisms to iron mineralization in a paleoaquifer

Karrie ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

Adolescent and young adult requests for medication abortion through online telemedicine

Researchers want a better whiff of plant-based proteins

Pioneering a new generation of lithium battery cathode materials

A Pitt-Johnstown professor found syntax in the warbling duets of wild parrots

Cleaner solar manufacturing could cut global emissions by eight billion tonnes

Safety and efficacy of stereoelectroencephalography-guided resection and responsive neurostimulation in drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy

Assessing safety and gender-based variations in cardiac pacemakers and related devices

New study reveals how a key receptor tells apart two nearly identical drug molecules

Parkinson’s disease triggers a hidden shift in how the body produces energy

Eleven genetic variants affect gut microbiome

Study creates most precise map yet of agricultural emissions, charts path to reduce hotspots

When heat flows like water

Study confirms Arctic peatlands are expanding

KRICT develops microfluidic chip for one-step detection of PFAs and other pollutants

How much can an autonomous robotic arm feel like part of the body

Cell and gene therapy across 35 years

Rapid microwave method creates high performance carbon material for carbon dioxide capture

New fluorescent strategy could unlock the hidden life cycle of microplastics inside living organisms

HKUST develops novel calcium-ion battery technology enhancing energy storage efficiency and sustainability

High-risk pregnancy specialists present research on AI models that could predict pregnancy complications

Academic pressure linked to increased risk of depression risk in teens

[Press-News.org] Key part of plants' rapid response system revealedInternational collaboration puts molecular face on enzyme family that allows plants to adjust quickly to changing conditions