(Press-News.org) UPTON, N.Y. — Overturning two long-held misconceptions about oil production in algae, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory show that ramping up the microbes' overall metabolism by feeding them more carbon increases oil production as the organisms continue to grow. The findings — published online in the journal Plant and Cell Physiology on May 28, 2012 — may point to new ways to turn photosynthetic green algae into tiny "green factories" for producing raw materials for alternative fuels.

"We are interested in algae because they grow very quickly and can efficiently convert carbon dioxide into carbon-chain molecules like starch and oils," said Brookhaven biologist Changcheng Xu, the paper's lead author. With eight times the energy density of starch, algal oil in particular could be an ideal raw material for making biodiesel and other renewable fuels.

But there have been some problems turning microscopic algae into oil producing factories.

For one thing, when the tiny microbes take in carbon dioxide for photosynthesis, they preferentially convert the carbon into starch rather than oils. "Normally, algae produce very little oil," Xu said.

Before the current research, the only way scientists knew to tip the balance in favor of oil production was to starve the algae of certain key nutrients, like nitrogen. Oil output would increase, but the algae would stop growing — not ideal conditions for continuous production.

Another issue was that scientists didn't know much about the details of oil biochemistry in algae. "Much of what we thought we knew was inferred from studies performed on higher plants," said Brookhaven biochemist John Shanklin, a co-author who's conducted extensive research on plant oil production. Recent studies have hinted at big differences between the microbial algae and their more complex photosynthetic relatives.

"Our goal was to learn all we could about the factors that contribute to oil production in algae, including those that control metabolic switching between starch and oil, to see if we could shift the balance to oil production without stopping algae growth," Xu said.

The scientists grew cultures of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii — the "fruit fly" of algae — under a variety of nutrient conditions, with and without inhibitors that would limit specific biochemical pathways. They also studied a mutant Chlamydomonas that lacks the capacity to make starch. By comparing how much oil accumulated over time in the two strains across the various conditions, they were able to learn why carbon preferentially partitions into starch rather than oil, and how to affect the process.

The main finding was that feeding the algae more carbon (in the form of acetate) quickly maxed out the production of starch to the point that any additional carbon was channeled into high-gear oil production. And, most significantly, under the excess carbon condition and without nutrient deprivation, the microbes kept growing while producing oil.

"This overturns the previously held dogma that algae growth and increased oil production are mutually exclusive," Xu said.

The detailed studies, conducted mainly by Brookhaven research associates Jilian Fan and Chengshi Yan, showed that the amount of carbon was the key factor determining how much oil was produced: more carbon resulted in more oil; less carbon limited production. This was another surprise because a lot of approaches for increasing oil production have focused on the role of enzymes involved in producing fatty acids and oils. In this study, inhibiting enzyme production had little effect on oil output.

"This is an example of a substantial difference between algae and higher plants," said Shanklin.

In plants, the enzymes directly involved in the oil biosynthetic pathway are the limiting factors in oil production. In algae, the limiting step is not in the oil biosynthesis itself, but further back in central metabolism.

This is not all that different from what we see in human metabolism, Xu points out: Eating more carbon-rich carbohydrates pushes our metabolism to increase oil (fat) production and storage.

"It's kind of surprising that, in some ways, we're more like algae than higher plants are," Xu said, noting that scientists in other fields may be interested in the details of metabolic switching uncovered by this research.

But the next step for the Brookhaven team will be to look more closely at the differences in carbon partitioning in algae and plants. This part of the work will be led by co-author Jorg Schwender, an expert in metabolic flux studies. The team will also work to translate what they've learned in a model algal species into information that can help increase the yield of commercial algal strains for the production of raw materials for biofuels.

###This research was funded by the DOE Office of Science and the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov/" .

Related Links

Scientific Paper: "Oil accumulation is controlled by carbon precursor supply for fatty acid synthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii": http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22642988

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation for the State University of New York on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit, applied science and technology organization.

Visit Brookhaven Lab's electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more at http://www.bnl.gov/newsroom , or follow Brookhaven Lab on Twitter, http://twitter.com/BrookhavenLab .

Carbon is key for getting algae to pump out more oil

Findings may lead to new ways to produce raw materials for renewable fuels in microscopic 'green factories'

2012-06-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pediatric regime of chemotherapy proves more effective for young adults

2012-06-19

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), usually found in pediatric patients, is far more rare and deadly in adolescent and adult patients. According to the National Marrow Donor Program, child ALL patients have a higher than 80 percent remission rate, while the recovery rate for adults stands at only 40 percent.

In current practice, pediatric and young adult ALL patients undergo different treatment regimes. Children aged 0-15 years are typically given more aggressive chemotherapy, while young adults, defined as people between 16 and 39 years of age, are treated with a round ...

Key part of plants' rapid response system revealed

2012-06-19

Science has known about plant hormones since Charles Darwin experimented with plant shoots and showed that the shoots bend toward the light as long as their tips, which are secreting a growth hormone, aren't cut off.

But it is only recently that scientists have begun to put a molecular face on the biochemical systems that modulate the levels of plant hormones to defend the plant from herbivore or pathogen attack or to allow it to adjust to changes in temperature, precipitation or soil nutrients.

Now, a cross-Atlantic collaboration between scientists at Washington University ...

Peaches, plums, nectarines give obesity, diabetes slim chance

2012-06-19

COLLEGE STATION – Peaches, plums and nectarines have bioactive compounds that can potentially fight-off obesity-related diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to new studies by Texas AgriLife Research.

The study, which will be presented at the American Chemical Society in Philadelphia next August, showed that the compounds in stone fruits could be a weapon against "metabolic syndrome," in which obesity and inflammation lead to serious health issues, according to Dr. Luis Cisneros-Zevallos, AgriLife Research food scientist.

"In recent years obesity ...

Device implanted in brain has therapeutic potential for Huntington's disease

2012-06-19

Amsterdam, NL, June 18, 2012 – Studies suggest that neurotrophic factors, which play a role in the development and survival of neurons, have significant therapeutic and restorative potential for neurologic diseases such as Huntington's disease. However, clinical applications are limited because these proteins cannot easily cross the blood brain barrier, have a short half-life, and cause serious side effects. Now, a group of scientists has successfully treated neurological symptoms in laboratory rats by implanting a device to deliver a genetically engineered neurotrophic ...

Link between vitamin C and twins can increase seed production in crops

2012-06-19

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Biochemists at the University of California, Riverside report a new role for vitamin C in plants: promoting the production of twins and even triplets in plant seeds.

Daniel R. Gallie, a professor of biochemistry, and Zhong Chen, an associate research biochemist in the Department of Biochemistry, found that increasing the level of dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), a naturally occurring enzyme that recycles vitamin C in plants and animals, increases the level of the vitamin and results in the production of twin and triplet seedlings in a single seed.

The ...

Research breakthrough: High brain integration underlies winning performances

2012-06-19

Scientists trying to understand why some people excel — whether as world-class athletes, virtuoso musicians, or top CEOs — have discovered that these outstanding performers have unique brain characteristics that make them different from other people.

A study published in May in the journal Cognitive Processing found that 20 top-level managers scored higher on three measures — the Brain Integration Scale, Gibbs's Socio-moral Reasoning questionnaire, and an inventory of peak experiences — compared to 20 low-level managers that served as matched controls. This is the fourth ...

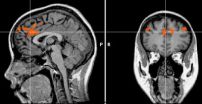

This is your brain on no self-control

2012-06-19

New pictures from the University of Iowa show what it looks like when a person runs out of patience and loses self-control.

A study by University of Iowa neuroscientist and neuro-marketing expert William Hedgcock confirms previous studies that show self-control is a finite commodity that is depleted by use. Once the pool has dried up, we're less likely to keep our cool the next time we're faced with a situation that requires self-control.

But Hedgcock's study is the first to actually show it happening in the brain using fMRI images that scan people as they perform self-control ...

Million year old groundwater in Maryland water supply

2012-06-19

A portion of the groundwater in the upper Patapsco aquifer underlying Maryland is over a million years old. A new study suggests that this ancient groundwater, a vital source of freshwater supplies for the region east of Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, was recharged over periods of time much greater than human timescales.

"Understanding the average age of groundwater allows scientists to estimate at what rate water is re-entering the aquifer to replace the water we are currently extracting for human use," explained USGS Director Marcia McNutt. "This is the first step ...

Anti-cocaine vaccine described in Human Gene Therapy Journal

2012-06-19

New Rochelle, NY, June 18, 2012—A single-dose vaccine capable of providing immunity against the effects of cocaine offers a novel and groundbreaking strategy for treating cocaine addiction is described in an article published Instant Online in Human Gene Therapy, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. (http://www.liebertpub.com) The article is available free online at the Human Gene Therapy website (http://www.liebertpub.com/hum).

"This is a very novel approach for addressing the huge medical problem of cocaine addiction," says James M. Wilson, MD, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, ...

Doctors cite concern for patients, colleagues top motives for working sick

2012-06-19

An unwavering work ethic is a hallmark of many health professionals. But a new survey finds that when a doctor is sick, staunch dedication can have unintended consequences.

A poll of 150 attendees of an American College of Physicians meeting in 2010 revealed that more than half of resident physicians had worked with flu-like symptoms at least once in the last year. One in six reported working sick on three or more occasions during the year, according to the survey conducted by researchers at the University of Chicago Medicine and Massachusetts General Hospital. Notably, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

Adolescent and young adult requests for medication abortion through online telemedicine

Researchers want a better whiff of plant-based proteins

Pioneering a new generation of lithium battery cathode materials

A Pitt-Johnstown professor found syntax in the warbling duets of wild parrots

Cleaner solar manufacturing could cut global emissions by eight billion tonnes

Safety and efficacy of stereoelectroencephalography-guided resection and responsive neurostimulation in drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy

Assessing safety and gender-based variations in cardiac pacemakers and related devices

New study reveals how a key receptor tells apart two nearly identical drug molecules

Parkinson’s disease triggers a hidden shift in how the body produces energy

Eleven genetic variants affect gut microbiome

Study creates most precise map yet of agricultural emissions, charts path to reduce hotspots

When heat flows like water

Study confirms Arctic peatlands are expanding

KRICT develops microfluidic chip for one-step detection of PFAs and other pollutants

How much can an autonomous robotic arm feel like part of the body

Cell and gene therapy across 35 years

Rapid microwave method creates high performance carbon material for carbon dioxide capture

New fluorescent strategy could unlock the hidden life cycle of microplastics inside living organisms

HKUST develops novel calcium-ion battery technology enhancing energy storage efficiency and sustainability

High-risk pregnancy specialists present research on AI models that could predict pregnancy complications

Academic pressure linked to increased risk of depression risk in teens

[Press-News.org] Carbon is key for getting algae to pump out more oilFindings may lead to new ways to produce raw materials for renewable fuels in microscopic 'green factories'