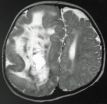

(Press-News.org) Hemimegalencephaly is a rare but dramatic condition in which the brain grows asymmetrically, with one hemisphere becoming massively enlarged. Though frequently diagnosed in children with severe epilepsy, the cause of hemimegalencephaly is unknown and current treatment is radical: surgical removal of some or all of the diseased half of the brain.

In a paper published in the June 24, 2012 online issue of Nature Genetics, a team of doctors and scientists, led by researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, say de novo somatic mutations in a trio of genes that help regulate cell size and proliferation are likely culprits for causing hemimegalencephaly, though perhaps not the only ones.

De novo somatic mutations are genetic changes in non-sex cells that are neither possessed nor transmitted by either parent. The scientists' findings – a collaboration between Joseph G. Gleeson, MD, professor of neurosciences and pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego; Gary W. Mathern, MD, a neurosurgeon at UC Los Angeles' Mattel Children's Hospital; and colleagues – suggest it may be possible to design drugs that inhibit or turn down signals from these mutated genes, reducing or even preventing the need for surgery.

Gleeson's lab studied a group of 20 patients with hemimegalencephaly upon whom Mathern had operated, analyzing and comparing DNA sequences from removed brain tissue with DNA from the patients' blood and saliva.

"Mathern had reported a family with identical twins, in which one had hemimegalencephaly and one did not. Since such twins share all inherited DNA, we got to thinking that there may be a new mutation that arose in the diseased brain that causes the condition," said Gleeson. Realizing they shared the same ideas about potential causes, the physicians set out to tackle this question using new exome sequencing technology, which allows sequencing of all of the protein-coding exons of the genome at the same time.

The researchers ultimately identified three gene mutations found only in the diseased brain samples. All three mutated genes had previously been linked to cancers.

"We found mutations in a high percentage of the cells in genes regulating the cellular growth pathways in hemimegalencephaly," said Gleeson. "These same mutations have been found in various solid malignancies, including breast and pancreatic cancer. For reasons we do not yet understand, our patients do not develop cancer, but rather this unusual brain condition. Either there are other mutations required for cancer propagation that are missing in these patients, or neurons are not capable of forming these types of cancers."

The mutations were found in 30 percent of the patients studied, indicating other factors are involved. Nonetheless, the researchers have begun investigating potential treatments that address the known gene mutations, with the clear goal of finding a way to avoid the need for surgery.

"Although counterintuitive, hemimegalencephaly patients are far better off following the functional removal or disconnection of the enlarged hemisphere," said Mathern. "Prior to the surgery, most patients have devastating epilepsy, with hundreds of seizures per day, completely resistant to even our most powerful anti-seizure medications. The surgery disconnects the affected hemisphere from the rest of the brain, causing the seizures to stop. If performed at a young age and with appropriate rehabilitation, most children suffer less language or cognitive delay due to neural plasticity of the remaining hemisphere."

But a less-invasive drug therapy would still be more appealing.

"We know that certain already-approved medications can turn down the signaling pathway used by the mutated genes in hemimegalencephaly," said lead author and former UC San Diego post-doctoral researcher Jeong Ho Lee, now at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. "We would like to know if future patients might benefit from such a treatment. Wouldn't it be wonderful if our results could prevent the need for such radical procedures in these children?"

INFORMATION:

Co-authors are My Huynh, department of Neurosurgery and Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Mattel Children's Hospital, Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA; Jennifer L. Silhavy, Tracy Dixon-Salazar, Andrew Heiberg, Eric Scott, Kiley J. Hill and Adrienne Collazo, Institute for Genomic Medicine, Rady Children's Hospital, UC San Diego and Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Sangwoo Kim and Vineet Bafna, Department of Computer Sciences, Jacobs School of Engineering, UC San Diego; Vincent Furnari and Carsten Russ, Institute for Medical Genetics, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles and Department of Pediatrics, Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA; and Stacey B. Gabriel, The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge.

Funding for this research came, in part, from the Daland Fellowship from the American Philosophical Society, the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 NS038992, R01 NS048453, R01 NS052455, R01 NS41537 and P01 HD070494), the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Gene mutations cause massive brain asymmetry

Discovery could help lead to prevention of radical surgery in rare childhood disease

2012-06-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Climate change and the South Asian summer monsoon

2012-06-25

The vagaries of South Asian summer monsoon rainfall impact the lives of more than one billion people. A review in Nature Climate Change (June 24 online issue) of over 100 recent research articles concludes that with continuing rise in CO2 and global warming, the region can expect generally more rainfall, due to the expected increase in atmospheric moisture, as well as more variability in rainfall.

In spite of the rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration of about 70 parts per million by volume and in global temperatures of about 0.50°C over the last 6 decades, the All India ...

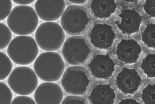

Faster, cheaper gas and liquid separation using custom designed and built mesoscopic structures

2012-06-25

Kyoto, Japan -- In what may prove to be a significant boon for industry, separating mixtures of liquids or gasses has just become considerably easier.

Using a new process they describe as "reverse fossilization," scientists at Kyoto University's WPI Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS) have succeeded in creating custom designed porous substances capable of low cost, high efficiency separation.

The process takes place in the mesoscopic realm, between the nano- and the macroscopic, beginning with the creation of a shaped mineral template, in this case ...

Significant sea-level rise in a 2-degree warming world

2012-06-25

The study is the first to give a comprehensive projection for this long perspective, based on observed sea-level rise over the past millennium, as well as on scenarios for future greenhouse-gas emissions.

"Sea-level rise is a hard to quantify, yet critical risk of climate change," says Michiel Schaeffer of Climate Analytics and Wageningen University, lead author of the study. "Due to the long time it takes for the world's ice and water masses to react to global warming, our emissions today determine sea levels for centuries to come."

Limiting global warming could considerably ...

Higher medical home performance rating of community health centers linked with higher operating cost

2012-06-25

CHICAGO – Federally funded community health centers with higher patient-centered medical home ratings on measures such as quality improvement had higher operating costs, according to a study appearing in JAMA. This study is being published early online to coincide with its presentation at the Annual Research Meeting of AcademyHealth.

"The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a model of care characterized by comprehensive primary care, quality improvement, care management, and enhanced access in a patient-centered environment. The PCMH is intuitively appealing and has ...

Better looking birds have more help at home with their chicks

2012-06-25

In choosing a mate both males and females rely on visual cues to determine which potential partner will supply the best genes, best nesting site, best territory, and best parenting skills. New research published in BioMed Central's open access journal Frontiers in Zoology shows that male blue tits' (Cyanistes caeruleus) parental behavior is determined by female ornamentation (ultraviolet coloration of the crown), as predicted by the differential allocation hypothesis (DAH).

DAH makes the assumption that aesthetic traits indicate quality and arises from the needs of a ...

Offenders need integrated, on-going, mental health care

2012-06-25

Offenders with mental health problems need improved and on-going access to health care, according to the first study to systematically examine healthcare received by offenders across the criminal justice system.

A new report from Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, Plymouth University, and the Centre for Mental Health, suggests that prison and community sentences offer the best opportunities to provide this. If improvements to mental health are to contribute to breaking the cycle of repeat offending, unemployment and ill-health, advantage should be taken of ...

Learn that tune while fast asleep

2012-06-25

EVANSTON, Ill. – Want to nail that tune that you've practiced and practiced? Maybe you should take a nap with the same melody playing during your sleep, new provocative Northwestern University research suggests.

The research grows out of exciting existing evidence that suggests that memories can be reactivated during sleep and storage of them can be strengthened in the process.

In the Northwestern study, research participants learned how to play two artificially generated musical tunes with well-timed key presses. Then while the participants took a 90-minute nap, the ...

Type 2 diabetes cured by weight loss surgery returns in one-fifth of patients

2012-06-25

A new study shows that although gastric bypass surgery reverses Type 2 diabetes in a large percentage of obese patients, the disease recurs in about 21 percent of them within three to five years. The study results will be presented Saturday at The Endocrine Society's 94th Annual Meeting in Houston.

"The recurrence rate was mainly influenced by a longstanding history of Type 2 diabetes before the surgery," said the study's lead author, Yessica Ramos, MD, an internal medicine resident at Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale. "This suggests that early surgical intervention ...

Study identifies causes for high rates of allergic reactions in children with food allergies

2012-06-25

A team of researchers from Mount Sinai School of Medicine and four other institutions have found that young children with documented or likely allergies to milk and/or eggs, whose families were instructed on how to avoid these and other foods, still experienced allergic reactions at a rate of almost once per year. Of severe cases, less than a third received epinephrine, a medication used to counter anaphylaxis, a life-threatening allergic condition.

The findings are from an ongoing Consortium of Food Allergy Research (CoFAR) study that has been following more than 500 ...

Mount Sinai researcher finds timing of ADHD medication affect academic progress

2012-06-25

A team of researchers led by an epidemiologist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine and University of Iceland has found a correlation between the age at which children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) begin taking medication, and how well they perform on standardized tests, particularly in math.

The study, titled, "A Population-Based Study of Stimulant Drug Treatment of ADHD and Academic Progress in Children," appears in the July, 2012, edition of Pediatrics, and can be viewed online on June 25. Using data from the Icelandic Medicines Registry and the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

[Press-News.org] Gene mutations cause massive brain asymmetryDiscovery could help lead to prevention of radical surgery in rare childhood disease