(Press-News.org) As the medical community continues to make positive strides in personalized cancer therapy, scientists know some dead ends are unavoidable. Drugs that target specific genes in cancerous cells are effective, but not all proteins are targetable. In fact, it has been estimated that as few as 10 to 15 percent of human proteins are potentially targetable by drugs. For this reason, Georgia Tech researchers are focusing on ways to fight cancer by attacking defective genes before they are able to make proteins.

Professor John McDonald is studying micro RNAs (miRNAs), a class of small RNAs that interact with messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that have been linked to a number of diseases, including cancer. McDonald's lab placed two different miRNAs (MiR-7 and MiR-128) into ovarian cancer cells and watched how they affected the gene system. The findings are published in the current edition of the journal BMC Medical Genomics.

"Each inserted miRNA created hundreds of thousands of gene expression changes, but only about 20 percent of them were caused by direct interactions with mRNAs," said McDonald. "The majority of the changes were indirect – they occurred downstream and were consequences of the initial reactions."

McDonald initially wondered if those secondary interactions could be a setback for the potential use of miRNAs, because most of them changed the gene expressions of something other than the intended targets. However, McDonald noticed that most of what changed downstream was functionally coordinated.

miR-7 transfection most significantly affected the pathways involved with cell adhesion, epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT) and other processes linked with cancer metastasis. The pathways most often affected by miR-128 transfection were different. They were more related to cell cycle control and processes involved with cellular replication – another process that is overactive in cancer cells.

"miRNAs have evolved for millions of years in order to coordinately regulate hundreds to thousands of genes together on the cellular level," said McDonald. "If we can understand which miRNAs affect which suites of genes and their coordinated functions, it could allow clinicians to attack cancer cells on a systems level, rather than going after genes individually."

Clinical trials for miRNAs are just beginning to be explored, but definitive findings are likely still years away because there are hundreds of miRNAs whose cellular functions must be fully understood. Another challenge facing scientists is developing ways to effectively target therapeutic miRNAs to cancer cells, something McDonald and his Georgia Tech peers are also investigating.

###McDonald is a professor in the School of Biology in Georgia Tech's College of Sciences.

Using millions of years of cell evolution in the fight against cancer

2012-08-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UCF nanoparticle discovery opens door for pharmaceuticals

2012-08-08

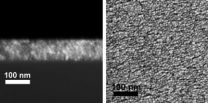

What a University of Central Florida student thought was a failed experiment has led to a serendipitous discovery hailed by some scientists as a potential game changer for the mass production of nanoparticles.

Soroush Shabahang, a graduate student in CREOL (The College of Optics & Photonics), made the finding that could ultimately change the way pharmaceuticals are produced and delivered.

The discovery was based on using heat to break up long, thin fibers into tiny, proportionally sized seeds, which have the capability to hold multiple types of materials locked in ...

New drug successfully halts fibrosis in animal model of liver disease

2012-08-08

A study published in the online journal Hepatology reports a potential new NADPH oxidase (NOX) inhibitor therapy for liver fibrosis, a scarring process associated with chronic liver disease that can lead to loss of liver function.

"While numerous studies have now demonstrated that advanced liver fibrosis in patients and in experimental rodent models is reversible, there is currently no effective therapy for patients," said principal investigator David A. Brenner, MD, vice chancellor for Health Sciences and dean of the School of Medicine at the University of California, ...

Chemists advance clear conductive thin films

2012-08-08

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In a touch-screen display or a solar panel, any conductive overlay had better be clear. Engineers employ transparent thin films of indium tin oxide (ITO) for the job, but a high-tech material's properties are only half its resume. They must also be as cheap and easy to manufacture as possible. In a new study, researchers from Brown University and ATMI Inc. report the best-ever transparency and conductivity performance for an ITO made using a chemical solution, which is potentially the facile, low-cost method manufacturers want.

"Our ...

Diseased trees new source of climate gas

2012-08-08

Diseased trees in forests may be a significant new source of methane that causes climate change, according to researchers at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in Geophysical Research Letters.

Sixty trees sampled at Yale Myers Forest in northeastern Connecticut contained concentrations of methane that were as high as 80,000 times ambient levels. Normal air concentrations are less than 2 parts per million, but the Yale researchers found average levels of 15,000 parts per million inside trees.

"These are flammable concentrations," said Kristofer Covey, ...

Researchers demonstrate control of devastating cassava virus in Africa

2012-08-08

ST. LOUIS, MO, August 7, 2012— An international research collaboration recently demonstrated progress in protecting cassava against cassava brown streak disease (CBSD), a serious virus disease, in a confined field trial in Uganda using an RNA interference technology. The field trial was planted in November 2010 following approval by the National Biosafety Committee of Uganda. The plants were harvested in November 2011 and results were published in the August 1, 2012 issue of the journal Molecular Plant Pathology . These results point researchers in the right direction ...

GEN reports on recent progress in Alzheimer's research

2012-08-08

New Rochelle, NY, August 7, 2012—The global market value of Alzheimer's disease therapeutics could soar to the $8 billion range once therapeutics are approved that actually change the course of the disease, reports Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News (GEN). The current therapeutic market is valued at $3 to $4 billion, shared among drugs that temporarily delay disease progression or address the symptoms but do not alter the underlying disease, according to a recent issue of GEN.

"Despite all the research on amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles there is still ...

Notre Dame researcher is shedding light on how jaws evolve

2012-08-08

If you're looking for information on the evolution and function of jaws, University of Notre Dame researcher Matt Ravosa is your man.

His integrative research program investigates major adaptive and morphological transformations in the mammalian musculoskeletal system during development and across higher-level groups. In mammals, the greater diversification and increasingly central role of the chewing complex in food procurement and processing has drawn considerable attention to the biomechanics and evolution of this system. Being among the most highly mineralized, and ...

Can nature parks save biodiversity?

2012-08-08

The 14 years of wildlife studies in and around Madagascar's Ranomafana National Park by Sarah Karpanty, associate professor of wildlife conservation at Virginia Tech's College of Natural Resources and Environment, and her students are summarily part of a paper on biodiversity published July 25 by Nature's Advanced Online Publication and coming out soon in print.

As human activities put increasing pressures on natural systems and wildlife to survive, 200 scientists around the world carved up pieces of the puzzle to present a clearer picture of reality and find ways to mitigate ...

Planting the seeds of defense

2012-08-08

LA JOLLA, CA----It was long thought that methylation, a crucial part of normal organism development, was a static modification of DNA that could not be altered by environmental conditions. New findings by researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, however, suggest that the DNA of organisms exposed to stress undergo changes in DNA methylation patterns that alter how genes are regulated.

The scientists found that exposure to a pathogenic bacteria caused widespread changes in a plant's epigenetic code, an extra layer of biochemical instructions in DNA that ...

Increasing federal match funds for states boosts enrollment of kids in health-care programs

2012-08-08

Ann Arbor, Mich. — Significantly more children get health insurance coverage after increases in federal matching funds to states for Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), according to new research from the University of Michigan.

The research, published Monday in the journal Health Affairs, showed that a 10-percentage-point increase in the federal match for Medicaid and CHIP, similar to the increase that occurred with the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act, is associated with an increase of 1.9 percent in the number of children enrolled in ...