(Press-News.org) At its most fundamental level, diabetes is a disease characterized by stress -- microscopic stress that causes inflammation and the loss of insulin production in the pancreas, and system-wide stress due to the loss of that blood-sugar-regulating hormone.

Now, researchers led by scientists at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have uncovered a new key player in amplifying this stress in the earliest stages of diabetes: a molecule called thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP). The molecule, they've discovered, is central to the inflammatory process that leads to the death of the cells in the human pancreas that produce insulin.

"This molecule does something remarkable -- it takes stress and makes it worse," said the senior author of the study, UCSF's Feroz Papa, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine at UCSF and a member of the UCSF Diabetes Center and the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3).

The study is published this week in the journal Cell Metabolism, with a parallel study by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis. Both studies were funded by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF).

The work provides a roadmap for finding new drugs that could target and shut down the action of TXNIP, thus preventing or stalling the inflammatory processes it amplifies. Researchers in the field believe that this strategy could benefit people in the early days of the disease, when diabetes is first developing or is soon to develop -- a time referred to as the "honeymoon" period.

Clinical studies have already shown that dietary changes and other approaches can extend the honeymoon period in some people and prevent diabetes in others. The overarching goal of Papa's research, he said, is to find a way to extend this honeymoon period indefinitely.

Diabetes and the Loss of Beta Cells

Diabetes is a major health concern in the United States, affecting an estimated 8.3 percent of the U.S. population -- some 25.8 million Americans -- and costing U.S. taxpayers more than $200 billion annually. In California alone, an estimated 4 million people (one out of every seven adults) has type 2 diabetes, and millions more are at risk of developing it. These numbers are poised to explode in the next half century if more is not done to prevent the disease.

At the heart of diabetes is the specialized hormone-producing beta cells, which dot the human pancreas and produce the insulin that helps regulate a person's blood sugar.

These beta cells are like tiny biological factories that churn out insulin. A single beta cell might make a million molecules of insulin a minute. That means the billion or so beta cells in the average healthy pancreas will make more copies of insulin every year than there are grains of sand on every beach and in every desert in the world.

They are part of a delicate balance, however, and if the beta cells are lost, the pancreas may not be able to produce enough insulin and the body may not be able maintain proper blood sugar levels. That's exactly what happens in diabetes.

Stress to the Cells

Papa and his colleagues have found in recent years that underlying beta cell destruction and diabetes is stress within a part of the cell known as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

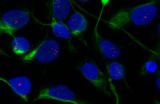

All cells have these structures, and the enveloped folds of the ER are easily spotted under a microscope. They play a crucial role in all human cells by helping to process and fold proteins the cells produce. But for beta cells, this structure is critical to their specialized function of secreting insulin.

If one thinks of a beta cell as a little factory, the ER would be like the shipping warehouse -- the packaging place where the end products are nicely wrapped, tagged with address labels, and sent to their final destination.

A healthy ER is like a well-run warehouse. Items are processed, packaged and shipped efficiently. A stressed ER, however, resembles a warehouse in shambles, with unboxed cargo accumulating everywhere. The longer this continues, the worse it becomes, and the body's solution to the problem is somewhat drastic: it essentially burns the factory down and closes the warehouse.

In scientific terms, the cell initiates what is known as the "unfolded protein response" in the ER, which activates inflammation through a protein known as interleukin-1 (IL-1). This process ultimately leads to apoptosis, the self-implosion of the beta cell.

For a whole organism, this is not as drastic as it sounds—with a billion or more beta cells in the pancreas, most people can afford to lose a few. The problem is that for far too many people, there are far too many warehouses burning down.

"There's not a lot of reserve in the human pancreas -- if these cells start dying, the remaining cells have to work harder," Papa said. Past some tipping point, the balance is lost and diabetes develops.

The Discovery of TXNIP's Role

Recognizing the importance of the inflammatory process in the development of diabetes, several pharmaceutical companies already have clinical trials underway to test potential new drugs that target the IL-1 protein.

In the new work, the UCSF team highlighted the protein TXNIP as a potential new target, until now an underappreciated central player in this process. TXNIP is involved in initiation of this destructive process of ER stress, unfolded protein response, inflammation and cell death.

They found that, as this process begins, a protein called IRE1 induces TXNIP, which leads directly to IL-1 production and inflammation. Removing TXNIP from the equation protects cells from death. In fact, when mice without this protein are bred with mice prone to developing diabetes, the offspring are completely protected against the disease because their insulin-producing beta cells survive.

What this suggests, said Papa, is that inhibiting TXNIP in people may protect their beta cells, perhaps delaying the onset of diabetes -- an idea that that will now have to be developed, translated and tested in clinical trials.

INFORMATION:

The article "IRE1a Induces Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein to Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Promote Programmed Cell Death under Irremediable ER Stress" by Alana G. Lerner, John-Paul Upton, P.V.K. Praveen, Rajarshi Ghosh, Yoshimi Nakagawa, Aeid Igbaria, Sarah Shen, Vinh Nguyen, Bradley J. Backes, Myriam Heiman, Nathaniel Heintz, Paul Greengard, Simon Hui, Qizhi Tang, Ala Trusina, Scott A. Oakes and Feroz R. Papa appears in the

See: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.007

The work was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) and Burroughs Wellcome Fund and from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the NIH Director's Office (a New Innovator Award in 2007) and grants from the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care.

Follow UCSF

UCSF.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | Twitter.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

A molecule central to diabetes is uncovered

UCSF study suggests stress-amplifying 'TXNIP' protein may be powerful new drug target

2012-08-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study sheds light on underlying causes of impaired brain function in muscular dystrophy

2012-08-08

The molecular missteps that disrupt brain function in the most common form of adult-onset muscular dystrophy have been revealed in a new study published by Cell Press. Myotonic dystrophy is marked by progressive muscle wasting and weakness, as well as excessive daytime sleepiness, memory problems, and mental retardation. A new mouse model reported in the August 9 issue of the journal Neuron reproduces key cognitive and behavioral symptoms of this disease and could be used to develop drug treatments, which are currently lacking.

"The new animal model reproduces important ...

The first public data release from BOSS, the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey

2012-08-08

The Third Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS-III) has issued Data Release 9 (DR9), the first public release of data from the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS). In this release BOSS, the largest of SDSS-III's four surveys, provides spectra for 535,995 newly observed galaxies, 102,100 quasars, and 116,474 stars, plus new information about objects in previous Sloan surveys (SDSS-I and II).

"This is just the first of three data releases from BOSS," says David Schlegel of the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), an astrophysicist ...

EARTH: Shake, rattle and roll

2012-08-08

Alexandria, VA – A team of researchers may have discovered a way to hear earthquakes. Not the noises of rattling windows and crumbling buildings, but the real sounds an earthquake makes deep underground as rock grinds and fails catastrophically. Typical seismic waves have frequencies below the audible range for humans, but the August issue of EARTH shows you where to find the voice of one seismic monster: the March 11, 2011, magnitude-9.0 Tohoku earthquake in Japan.

Beyond the novelty of simply hearing an earthquake, the team found that the new technology could possibly ...

UK hotel industry alive with innovation

2012-08-08

Large hotel chains are quick to adopt and adapt innovations developed in other industries, while smaller hotels make almost continual incremental changes in response to customers' needs. The UK hotel industry is alive with innovation and new ways of improving service for customers, research funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) has found.

The findings of a project led by Professor Gareth Shaw of Exeter University and Professor Allan Williams of Surrey University run counter to the traditional image of the hotel sector as slow to change. Official measures ...

Unusual weather events identified during the Black Saturday bushfires

2012-08-08

Research has revealed that the extremely hot, dry and windy conditions on Black Saturday combined with structures in the atmosphere called 'horizontal convective rolls' -similar to streamers of wind flowing through the air - which likely affected fire behaviour.

The study is the first of its kind to produce such detailed, high-resolution simulations of weather patterns on the day and provides insights for future fire management and warning systems.

The work was led by Dr Todd Lane and Ms Chermelle Engel from The University of Melbourne with Prof Michael Reeder (Monash ...

Benefit of PET and PET/CT in ovarian cancer is not proven

2012-08-08

Due to the lack of studies, there is currently no proof that patients with ovarian cancer can benefit from positron emission tomography (PET) alone or in combination with computed tomography (CT). As regards diagnostic accuracy, in certain cases, recurrences can be detected earlier and more accurately with PET or PET/CT than with conventional imaging techniques. This is the conclusion of the final report by the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) in Cologne that was published on 23 May 2012.

More reliable diagnosis is supposed to improve ...

Queen's University Belfast makes significant cancer breakthrough

2012-08-08

A major breakthrough by scientists at Queen's University Belfast could lead to more effective treatments for throat and cervical cancer.

The discovery could see the development of new therapies, which would target the non-cancerous cells surrounding a tumour, as well as treating the tumour itself.

Researchers at Queen's Centre for Cancer Research and Cell Biology have found that the non-cancerous tissue, or 'stroma', surrounding cancers of the throat and cervix, plays an important role in regulating the spread of cancer cells.

The discovery opens the door for the development ...

Scientists discover the truth behind Colbert's 'truthiness'

2012-08-08

Trusting research over their guts, scientists in New Zealand and Canada examined the phenomenon Stephen Colbert, comedian and news satirist, calls "truthiness"—the feeling that something is true. In four different experiments they discovered that people believe claims are true, regardless of whether they actually are true, when a decorative photograph appears alongside the claim. The work is published online in the Springer journal, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

"We wanted to examine how the kinds of photos people see every day—the ones that decorate newspaper or TV ...

Humanities mini-courses for doctors sharpen thinking and creativity

2012-08-08

Mini-courses designed to increase creative stimulation and variety in physicians' daily routines can sharpen critical thinking skills, improve job satisfaction and encourage innovative thinking, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers who piloted a series of such courses.

"For decades, career development theory has identified a stage that occurs at midlife, characterized by a desire to escape the status quo and pursue new ventures," said Kimberly Myers, Ph.D., associate professor of humanities. "It is increasingly clear that these mid-career professionals ...

Berlin beats London and Washington in league table of world's best democratic space

2012-08-08

New research from the University of Warwick suggests that Berlin has the best democratic space in the world, topping a list that includes London, Washington and Tokyo.

The list appears in a new book, 'Democracy and Public Space: The Physical Sites of Democratic Performance' written by Dr John Parkinson, from the University of Warwick's Politics and International Studies department.

Dr Parkinson carefully selected 11 capital cities and assessed how well they provide space for all kinds of democratic action. He visited Berlin, Washington, Ottawa, Canberra, Wellington, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

[Press-News.org] A molecule central to diabetes is uncoveredUCSF study suggests stress-amplifying 'TXNIP' protein may be powerful new drug target