BUSM/VA researchers uncover gender differences in the effects of long-term alcoholism

2012-08-10

(Press-News.org) (Boston) – Researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) and Veterans Affairs (VA) Boston Healthcare System have demonstrated that the effects on white matter brain volume from long-term alcohol abuse are different for men and women. The study, which is published online in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, also suggests that with abstinence, women recover their white matter brain volume more quickly than men.

The study was led by Susan Mosher Ruiz, PhD, postdoctoral research scientist in the Laboratory for Neuropsychology at BUSM and research scientist at the VA Boston Healthcare System, and Marlene Oscar Berman, PhD, professor of psychiatry, neurology and anatomy and neurobiology at BUSM and research career scientist at the VA Boston Healthcare System.

In previous research, alcoholism has been associated with white matter pathology. White matter forms the connections between neurons, allowing communication between different areas of the brain. While previous neuroimaging studies have shown an association between alcoholism and white matter reduction, this study furthered the understanding of this effect by examining gender differences and utilizing a novel region-of-interest approach.

The research team employed structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine the effects of drinking history and gender on white matter volume. They examined brain images from 42 abstinent alcoholic men and women who drank heavily for more than five years and 42 nonalcoholic control men and women. Looking at the correlation between years of alcohol abuse and white matter volume, the researchers found that a greater number of years of alcohol abuse was associated with smaller white matter volumes in the abstinent alcoholic men and women. In the men, the decrease was observed in the corpus callosum while in women, this effect was observed in cortical white matter regions.

"We believe that many of the cognitive and emotional deficits observed in people with chronic alcoholism, including memory problems and flat affect, are related to disconnections that result from a loss of white matter," said Mosher Ruiz.

The researchers also examined if the average number of drinks consumed per day was associated with reduced white matter volume. They found that the number of daily drinks did have a strong impact on alcoholic women, and the volume loss was one and a half to two percent for each additional daily drink. Additionally, there was an eight to 10 percent increase in the size of the brain ventricles, which are areas filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that play a protective role in the brain. When white matter dies, CSF produced in the ventricles fills the ventricular space.

Recovery of white matter brain volume also was examined. They found that, in men, the corpus callosum recovered at a rate of one percent per year for each additional year of abstinence. For people who abstained less than a year, the researchers found evidence of increased white matter volume and decreased ventricular volume in women, but not at all in men. However, for people in recovery for more than a year, those signs of recovery disappeared in women and became apparent in men.

"These findings preliminarily suggest that restoration and recovery of the brain's white matter among alcoholics occurs later in abstinence for men than for women," said Mosher Ruiz. "We hope that additional research in this area can help lead to improved treatment methods that include educating both alcoholic men and women about the harmful effects of excessive drinking and the potential for recovery with sustained abstinence."

###

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01-AA07112 and K05-AA00219, the US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service and the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies (award number P41RR14075).

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2012-08-10

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Earthworms creep along the ground by alternately squeezing and stretching muscles along the length of their bodies, inching forward with each wave of contractions. Snails and sea cucumbers also use this mechanism, called peristalsis, to get around, and our own gastrointestinal tracts operate by a similar action, squeezing muscles along the esophagus to push food to the stomach.

Now researchers at MIT, Harvard University and Seoul National University have engineered a soft autonomous robot that moves via peristalsis, crawling across surfaces by contracting ...

2012-08-10

NASA scientist Tom Hanisco is helping to fill a big gap in scientists' understanding of how much urban pollution -- and more precisely formaldehyde -- ultimately winds up in Earth's upper atmosphere where it can wreak havoc on Earth's protective ozone layer.

He and his team at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., have developed an automated, lightweight, laser-induced fluorescence device that measures the levels of this difficult-to-measure organic compound in the lower troposphere and then again at much higher altitudes. The primary objective is determining ...

2012-08-10

Many of the long term goals people strive for — like losing weight — require us to use self-control and forgo immediate gratification. And yet, denying our immediate desires in order to reap future benefits is often very hard to do.

In a new article in the August issue of Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, researchers Kentaro Fujita and Jessica Carnevale of The Ohio State University propose that the way people subjectively understand, or construe, events can influence self-control.

Research from psychological ...

2012-08-10

NEW YORK, N.Y. (August 9, 2012) – Over 400 attendees from across the U.S. and around the world participated in the first national conference for families and professionals, "Treating the Whole Person with Autism: Comprehensive Care for Children and Adolescents with ASD."

Autism Speaks, the world's leading autism science and advocacy organization, organized and hosted the conference in collaboration with educational partners at Nationwide Children's Hospital (NCH), The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Health ...

2012-08-10

VIDEO:

Researchers Alyssa Stark and Tim Sullivan test the adhesion of a geckos feet in water. Their findings may help improve the adhesion of bandages, sutures and similar items in moist...

Click here for more information.

Akron, Ohio, August 9, 2012 — Scientists already know that the tiny hairs on geckos' toe pads enable them to cling, like Velcro, to vertical surfaces. Now, University of Akron researchers are unfolding clues to the reptiles' gripping power in wet conditions ...

2012-08-10

High, cold cloud tops with bitter cold temperatures are indicators that there's a lot of strength in the uplift of air within a tropical cyclone. NASA's Aqua satellite passed by Hurricane Gilma and saw a concentrated area of very cold cloud tops.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Hurricane Gilma on August 9 at 5:53 a.m. EDT. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument captured an infrared image of the cloud temperatures that showed the strongest storms and heaviest rainfall were wrapped around the storm's center. Cloud top temperatures in that area were as cold ...

2012-08-10

In patients with hoarding disorder, parts of a decision-making brain circuit under-activated when dealing with others' possessions, but over-activated when deciding whether to keep or discard their own things, a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded study has found. NIMH is part of the National Institutes of Health.

Brain scans revealed the abnormal activation in areas of the anterior cingulate cortex and insula known to process error monitoring, weighing the value of things, assessing risks, unpleasant feelings, and emotional decisions.

NIMH grantee David ...

2012-08-10

For years, many scientists had thought that plate tectonics existed nowhere in our solar system but on Earth. Now, a UCLA scientist has discovered that the geological phenomenon, which involves the movement of huge crustal plates beneath a planet's surface, also exists on Mars.

"Mars is at a primitive stage of plate tectonics. It gives us a glimpse of how the early Earth may have looked and may help us understand how plate tectonics began on Earth," said An Yin, a UCLA professor of Earth and space sciences and the sole author of the new research.

Yin made the discovery ...

2012-08-10

The possibility of an inexpensive, convenient test for Alzheimer's disease has been on the horizon for several years, but previous research leads have been hard to duplicate.

In a study to be published in the August 28 issue of the journal Neurology, scientists have taken a step toward developing a blood test for Alzheimer's, finding a group of markers that hold up in statistical analyses in three independent groups of patients.

"Reliability and failure to replicate initial results have been the biggest challenge in this field," says lead author William Hu, MD, PhD, ...

2012-08-10

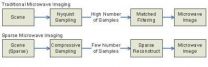

Sparse microwave imaging is a novel concept in microwave imaging that is intended to deal with the problems of increasing microwave imaging system complexity caused by the requirements of the system applications. Under the support of the 973 program "Study of theory, system and methodology of sparse microwave imaging", Chinese scientists have conducted considerable research into most aspects of sparse microwave imaging, including its fundamental theories, system design, performance evaluation and applications. Their work, consisting of a series of papers, was published ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] BUSM/VA researchers uncover gender differences in the effects of long-term alcoholism