(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. – Nanotechnology is about to emerge in the world of pesticides and pest control, and a range of new approaches are needed to understand the implications for public health, ensure that this is done safely, maximize the potential benefits and prevent possible risks, researchers say in a new report.

In a study published today in the International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, scientists from Oregon State University and the European Union outline six regulatory and educational issues that should be considered whenever nanoparticles are going to be used in pesticides.

"If we do it right, it should be possible to design nanoparticles with safety as a primary consideration, so they can help create pesticides that work better or are actually safer," said Stacey Harper, an assistant professor of nanotoxicology at Oregon State University. Harper is a national leader in the safety and environmental impacts of this science that deals with particles so extraordinarily small they can have novel and useful characteristics.

"Unlike some other applications of nanotechnology, which are further along in development, applications for pesticides are in their infancy," Harper said. "There are risks and a lot of uncertainties, however, so we need to understand exactly what's going on, what a particular nanoparticle might do, and work to eliminate use of any that do pose dangers."

A program is already addressing that at OSU, as part of the Oregon Nanoscience and Microtechnologies Institute.

The positive aspect of nanotechnology use with pesticides, researchers say, is that it might allow better control and delivery of active ingredients, less environmental drift, formulations that will most effectively reach the desired pest, and perhaps better protection for agricultural workers.

"If you could use less pesticide and still accomplish the same goal, that's a concept worth pursuing," Harper said.

But researchers need to be equally realistic about the dangers, she said. OSU labs have tested more than 200 nanomaterials, and very few posed any toxic concerns – but a few did. In one biomedical application, where nanoparticles were being studied as a better way to deliver a cancer drug, six out of 40 evoked a toxic response, most of which was linked to a specific surface chemistry that scientists now know to avoid.

"The emergence of nanotechnology in the pesticide industry has already begun, this isn't just theoretical," said David Stone, an assistant professor in the OSU Department of Environmental and Molecular Toxicology. "But pesticides are already one of the most rigorously tested and regulated class of compounds, so we should be able to modify the existing infrastructure."

One important concern, the researchers said, will be for manufacturers to disclose exactly what nanoparticles are involved in their products and what their characteristics are. Another issue is to ensure that compounds are tested in the same way humans would be exposed in the real world.

"You can't use oral ingestion of a pesticide by a laboratory rat and assume that will tell you what happens when a human inhales the same substance," Stone said. "Exposure of the respiratory tract to nanoparticles is one of our key concerns, and we have to test compounds that way."

Future regulations also need to acknowledge the additional level of uncertainty that will exist for nano-based pesticides with inadequate data, the scientists said in their report. Tests should be done using the commercial form of the pesticides, a health surveillance program should be initiated, and other public educational programs developed.

Special assessments may also need to be developed for nanoparticle exposure to sensitive populations, such as infants, the elderly, or fetal exposure. And new methodologies may be required to understand nanoparticle effects, which are different from most traditional chemical tests.

"These measures will require a coordinated effort between governmental, industry, academic and public entities to effectively deal with a revolutionary class of novel pesticides," the researchers concluded in their report.

###

Editor's Note: A digital image of nanoparticles is available online: http://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonstateuniversity/5042340155/

About the OSU College of Agricultural Sciences: The college contributes in many ways to the economic and environmental sustainability of Oregon and the Pacific Northwest. The college's faculty are leaders in agriculture and food systems, natural resources management, life sciences and rural economic development research.

New approaches needed to gauge safety of nanotech-based pesticides

2010-10-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Women executives twice as likely to leave their jobs as men

2010-10-05

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A new study has determined that female executives are more than twice as likely to leave their jobs – voluntarily and involuntarily – as men. Yet despite systemic evidence that women are more likely to depart from their positions, the researchers did not find strong patterns of discrimination.

Lead author John Becker-Blease, an assistant professor of finance at Oregon State University, and his co-authors at Loyola Marymount University and Trinity College, analyzed data from Standard & Poor's 1500 firms. They classified departures as voluntary or involuntary ...

X-rays linked to increased childhood leukemia risk

2010-10-05

Berkeley – Diagnostic X-rays may increase the risk of developing childhood leukemia, according to a new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley's School of Public Health.

Specifically, the researchers found that children with acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL) had almost twice the chance of having been exposed to three or more X-rays compared with children who did not have leukemia. For B-cell ALL, even one X-ray was enough to moderately increase the risk. The results differed slightly by the region of the body imaged, with a modest increase associated ...

Climate change affects horseshoe crab numbers

2010-10-05

Having survived for more than 400 million years, the horseshoe crab is now under threat – primarily due to overharvest and habitat destruction. However, climatic changes may

also play a role. Researchers from the University of Gothenburg reveal how sensitive horseshoe crab populations are to natural climate change in a study recently published

in the scientific journal Molecular Ecology.

The horseshoe crab is often regarded as a living fossil, in that it has survived almost unchanged in terms of body design and lifestyle for more than 400 million years. Crabs similar ...

New approach to underweight COPD patients

2010-10-05

Malnutrition often goes hand in hand with COPD and is difficult to treat. In a recent study researchers at the University of Gothenburg, have come up with a new equation to calculate the energy requirement for underweight COPD patients. It is hoped that

this will lead to better treatment results and, ultimately, better quality of life for these patients.

Recently published in the International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, the study involved a total of 86 patients with an average age of 64. In contrast to studies in other countries, more than half ...

Interactive media improved patients’ understanding of cancer surgery by more than a third

2010-10-05

Patients facing planned surgery answered 36 per cent more questions about the procedure correctly if they watched an interactive multimedia presentation (IMP) rather than just talking to medical staff, according to research in the October issue of the urology journal BJUI.

Researchers from the University of Melbourne, Australia, randomised 40 patients due to undergo radical prostatectomy into two groups. The first group went through the standard surgery consent process, where staff explained the procedure verbally, and the second group watched the IMP.

Both sets of ...

Depression and distress not detected in majority of patients seen by nurses -- new study

2010-10-05

New research from the University of Leicester reveals that nursing staff have 'considerable difficulty' detecting depression and distress in patients.

Two new research studies led by Dr Alex Mitchell, consultant in psycho-oncology at Leicestershire Partnership Trust and honorary senior lecturer at the University of Leicester, highlight the fact that while nurses are at the front line of caring for people, they receive little training in mental health.

The researchers call for the development of short, simple methods to identify mood problems as a way of providing more ...

Bonn researchers use light to make the heart stumble

2010-10-05

Tobias Brügmann and his colleagues from the University of Bonn's Institute of Physiology I used a so-called "channelrhodopsin" for their experiments, which is a type of light sensor. At the same time, it can act as an ion channel in the cell membrane. When stimulated with blue light, this channel opens, and positive ions flow into the cell. This causes a change in the cell membrane's pressure, which stimulates cardiac muscle cells to contract.

"We have genetically modified mice to make them express channelrhodopsin in the heart muscle," explains Professor Dr. Bernd Fleischmann ...

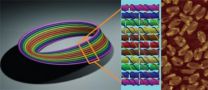

DNA art imitates life: Construction of a nanoscale Mobius strip

2010-10-05

The enigmatic Möbius strip has long been an object of fascination, appearing in numerous works of art, most famously a woodcut by the Dutchman M.C. Escher, in which a tribe of ants traverses the form's single, never-ending surface.

Scientists at the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University's and Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, led by Hao Yan and Yan Liu, have now reproduced the shape on a remarkably tiny scale, joining up braid-like segments of DNA to create Möbius structures measuring just 50 nanometers across—roughly the width of a virus particle. ...

Hebrew University research holds promise for development of new osteoporosis drug

2010-10-05

Jerusalem, October 4, 2010 – Researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have discovered a group of substances in the body that play a key role in controlling bone density, and on this basis they have begun development of a drug for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and other bone disorders.

The findings of the Hebrew University researchers have just been published in the American journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

The research group working on the project is headed by Prof. Itai Bab of the Bone Laboratory and Prof. Raphael ...

Disappearing glaciers enhanced biodiversity

2010-10-05

Biodiversity decreases towards the poles almost everywhere in the world, except along the South American Pacific coast. Investigating fossil clams and snails Steffen Kiel and Sven Nielsen at the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (CAU) could show that this unusual pattern originated at the end of the last ice age, 20.000 to 100.000 years ago. The retreating glaciers created a mosaic landscape of countless islands, bays and fiords in which new species developed rapidly – geologically speaking. The ancestors of the species survived the ice age in the warmer Chilean north.

The ...