(Press-News.org) The discovery of a 'switch' that modifies a gene known to be essential for normal heart development could explain variations in the severity of birth defects in children with DiGeorge syndrome.

Researchers from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute made the discovery while investigating foetal development in an animal model of DiGeorge syndrome. DiGeorge syndrome affects approximately one in 4000 babies.

Dr Anne Voss and Dr Tim Thomas led the study, with colleagues from the institute's Development and Cancer division, published today in the journal Developmental Cell.

Dr Voss said babies with DiGeorge syndrome have a characteristic DNA mutation on chromosome 22 (22q11 – chromosome 22, long arm, band 11), but exhibit a range of mild to severe birth defects, including heart and aorta defects. "The variation in symptoms is so prominent that even identical twins, with the exact same DNA sequence, can have remarkably different conditions," she said. "We hypothesised that environmental factors were probably responsible for the variation, via changes to the way in which genetic material is packaged in the chromatin," Dr Voss said.

Chromatin is the genetic material that comprises DNA and associated proteins packaged together in the cell nucleus. Chemical marks that sit on the chromatin modify it to instruct when and where to switch genes on or off, making a profound difference to normal development and cellular processes.

The research team found a protein called MOZ, the 'switch' which is involved in chromatin modification, was a key to explaining the range of defects seen in an animal model of DiGeorge syndrome. "MOZ is what we call an chromatin modifier, which means it is responsible for making marks on the chromatin that tell genes to switch on or off," Dr Voss said.

"In this study, we showed that MOZ regulates the major gene, called Tbx1, in the 22q11 deletion. Tbx1 is responsible for heart and aortic arch development. In mouse models that have no Moz gene, Tbx1 does not work properly, and the embryos have similar heart and aorta defects to those seen in children with DiGeorge syndrome. We showed that MOZ is crucial for normal activity of Tbx1, and the level of MOZ activity may contribute to determining how severe the defects are in children with DiGeorge syndrome," Dr Voss said.

Dr Voss said the study also showed that the severity of birth defects in DiGeorge syndrome could be compounded by the mother's diet, particularly if the MOZ switch is not working properly. The research team showed that reduced MOZ activity could conspire with excess retinoic acid (a type of vitamin A) to markedly increase the frequency and severity of DiGeorge syndrome.

"In our mouse model, we saw that retinoic acid exacerbated the defects seen in mice with mutations in the Moz gene. In fact, in mice that had one normal copy of MOZ and one mutated copy, the offspring look completely normal, but if the mother's diet was high in vitamin A, the offspring developed a DiGeorge-like syndrome. This suggests that MOZ, when coupled with a diet high in vitamin A (retinoic acid), may play a role in the development of DiGeorge syndrome in some cases.

"This interaction between the chromatin modifier MOZ, the Tbx1 gene, and retinoic acid in the diet gives a rare insight of how the environment and genetic mutations can interact at the chromatin level to cause birth defects."

###The work is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, British Heart Foundation, Australian Stem Cell Centre and the Victorian Government.

Gene 'switch' may explain DiGeorge syndrome severity

2012-08-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New insights into salt transport in the kidney

2012-08-23

Sodium chloride, better known as salt, is vital for the organism, and the kidneys play a crucial role in the regulation of sodium balance. However, the underlying mechanisms of sodium balance are not yet completely understood. Researchers of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin-Buch, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the University of Kiel have now deciphered the function of a gene in the kidney and have thus gained new insights into this complex regulation process (PNAS Early Edition, doi/10.1073/pnas.1203834109)*.

In humans, the kidneys ...

Cloud control could tame hurricanes, study shows

2012-08-23

They are one of the most destructive forces of nature on Earth, but now environmental scientists are working to tame the hurricane. In a paper, published in Atmospheric Science Letters, the authors propose using cloud seeding to decrease sea surface temperatures where hurricanes form. Theoretically, the team claims the technique could reduce hurricane intensity by a category.

The team focused on the relationship between sea surface temperature and the energy associated with the destructive potential of hurricanes. Rather than seeding storm clouds or hurricanes directly, ...

Canadian researcher is on a mission to create an equal playing field at the Paralympic Games

2012-08-23

Vancouver, BC – August 23, 2012 – Vancouver-based clinician and researcher Dr. Andrei Krassioukov is packing for the upcoming Paralympic games in London. Rather than packing sports equipment, he has a suitcase full of advanced scientific equipment funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation that he will use to monitor the cardiovascular function of athletes with spinal cord injuries.

Up to 90% of people with injuries between that cervical and high thoracic vertebrae suffer from a condition that limits their ability to regulate heart rate and blood pressure. For top-level ...

Scientists produce H2 for fuel cells using an inexpensive catalyst under real-world conditions

2012-08-23

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have produced hydrogen, H2, a renewable energy source, from water using an inexpensive catalyst under industrially relevant conditions (using pH neutral water, surrounded by atmospheric oxygen, O2, and at room temperature).

Lead author of the research, Dr Erwin Reisner, an EPSRC research fellow and head of the Christian Doppler Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, said: "A H2 evolution catalyst which is active under elevated O2 levels is crucial if we are to develop an industrial water splitting process - a chemical reaction ...

1-molecule-thick material has big advantages

2012-08-23

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The discovery of graphene, a material just one atom thick and possessing exceptional strength and other novel properties, started an avalanche of research around its use for everything from electronics to optics to structural materials. But new research suggests that was just the beginning: A whole family of two-dimensional materials may open up even broader possibilities for applications that could change many aspects of modern life.

The latest "new" material, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) — which has actually been used for decades, but not in its 2-D ...

Is this real or just fantasy? ONR Augmented-Reality Initiative progresses

2012-08-23

ARLINGTON, Va.—The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is demonstrating the next phase of an augmented-reality project Aug. 23 in Princeton, N.J., that will change the way warfighters view operational environments—literally.

ONR has completed the first year of a multi-year augmented-reality effort, developing a system that allow trainees to view simulated images superimposed on real-world landscapes. One example of augmented reality technology can be seen in sports broadcasts, which use it to highlight first-down lines on football fields and animate hockey pucks to help TV ...

Spacetime: A smoother brew than we knew

2012-08-23

Spacetime may be less like beer and more like sipping whiskey.

Or so an intergalactic photo finish may suggest.

Physicist Robert Nemiroff of Michigan Technological University reached this heady conclusion after studying the tracings of three photons of differing wavelengths that were recorded by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope in May 2009.

The photons originated about 7 billion light years away from Earth in one of three pulses from a gamma-ray burst. They arrived at the orbiting telescope just one millisecond apart, in a virtual tie.

Gamma-ray bursts are ...

Novel microscopy method offers sharper view of brain's neural network

2012-08-23

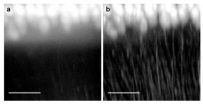

WASHINGTON, Aug. 23—Shortly after the Hubble Space Telescope went into orbit in 1990 it was discovered that the craft had blurred vision. Fortunately, Space Shuttle astronauts were able to remedy the problem a few years later with supplemental optics. Now, a team of Italian researchers has performed a similar sight-correcting feat for a microscope imaging technique designed to explore a universe seemingly as vast as Hubble's but at the opposite end of the size spectrum—the neural pathways of the brain.

"Our system combines the best feature of one microscopy technique—high-speed, ...

How to feed data-hungry mobile devices? Use more antennas

2012-08-23

Researchers from Rice University today unveiled a new multi-antenna technology that could help wireless providers keep pace with the voracious demands of data-hungry smartphones and tablets. The technology aims to dramatically increase network capacity by allowing cell towers to simultaneously beam signals to more than a dozen customers on the same frequency.

Details about the new technology, dubbed Argos, were presented today at the Association for Computing Machinery's MobiCom 2012 wireless research conference in Istanbul. Argos is under development by researchers from ...

Vanderbilt-led study reveals racial disparities in prostate cancer care

2012-08-23

A study led by investigators from Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC), Nashville, Tenn., finds that black men with prostate cancer receive lower quality surgical care than white men. The racial differences persist even when controlling for factors such as the year of surgery, age, comorbidities and insurance status.

Daniel Barocas, M.D., MPH, assistant professor of Urologic Surgery, is first author of the study published in the Aug. 17 issue of the Journal of Urology.

Investigators from VICC, the Tennessee Valley Veterans Administration Geriatric Research, Education ...