(Press-News.org) People will reject an offer of water, even when they are severely thirsty, if they perceive the offer to be unfair, according to a new study funded by the Wellcome Trust. The findings have important implications for understanding how humans make decisions that must balance fairness and self-interest.

It's been known for some time that when humans bargain for money they have a tendency to reject unfair offers, preferring to let both parties walk away with nothing rather than accept a low offer in the knowledge that their counterpart is taking home more cash.

In contrast, when bargaining for food, our closes relatives chimpanzees will almost always accept an offer regardless of any subjective idea of 'fairness'.

Researchers at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at UCL wanted to see whether humans would similarly accept unfair offers if they were bargaining for a basic physiological need, such as food, water or sex.

The team recruited 21 healthy participants and made 11 of them thirsty by drip-feeding them a salty solution, whilst the remainder received an isotonic solution that had a much smaller effect on their level of thirst. To obtain an objective measure of each individual's need for water, the team measured the salt concentration in their blood. The participants' subjective perception of how thirsty they were was assessed using a simple rating scale.

The participants then separately took part in an ultimatum game. They were given instructions that two of them had been randomly selected to play a game to decide the split of a 500ml bottle of water that could be consumed immediately. One of them would play the part of 'Proposer' and decide how the bottle should be split. The other would be a 'Responder' who could either accept the split and so drink the water offered to them, or reject the split so that both parties would get nothing. The participants knew that they would have to wait a full hour after the end of the game before they would have access to water.

In reality, all of the participants played the part of the Responder. They were presented with two glasses of water with a highly unequal offer that they were told was from the Proposer: the glass offered to them contained 62.5ml, an eighth of the original bottle of water, and the other contained the remaining seven eighths that the Proposer wanted to keep for themselves. They had fifteen seconds to decide whether to accept or reject the offer.

The team found that, unlike chimpanzees, the human participants tended to reject the highly unequal offer, and here that was the case even if they were severely thirsty. The participants' choices were not influenced by how thirsty they actually were, as measured objectively from the blood sample. However, they were more likely to accept the offer if they subjectively felt that they were thirsty.

Dr Nick Wright, who led the study, explains: "Whether or not fairness is a uniquely human motivation has been a source of controversy. These findings show that humans, unlike even our closest relatives chimpanzees, reject an unfair offer of a primary reward like food or water – and will do that even when severely thirsty. However, we also show this fairness motivation is traded-off against self-interest, and that this self-interest is not determined by how their objective need for water but instead by their subjective perception of thirst. These findings are interesting for understanding how subjective feelings of fairness and self-interested need impact on everyday decisions, for example in the labour market."

###The study is published online today in the open access journal Scientific Reports.

Study reveals human drive for fair play

2012-08-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Therapeutic avenues for Parkinson's investigated at UH

2012-08-23

HOUSTON, Aug. 23, 2012 – Scientists at the University of Houston (UH) have discovered what may possibly be a key ingredient in the fight against Parkinson's disease.

Affecting more than 500,000 people in the U.S., Parkinson's disease is a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system marked by a loss of certain nerve cells in the brain, causing a lack of dopamine. These dopamine-producing neurons are in a section of the midbrain that regulates body control and movement. In a study recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), ...

Gene 'switch' may explain DiGeorge syndrome severity

2012-08-23

The discovery of a 'switch' that modifies a gene known to be essential for normal heart development could explain variations in the severity of birth defects in children with DiGeorge syndrome.

Researchers from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute made the discovery while investigating foetal development in an animal model of DiGeorge syndrome. DiGeorge syndrome affects approximately one in 4000 babies.

Dr Anne Voss and Dr Tim Thomas led the study, with colleagues from the institute's Development and Cancer division, published today in the journal Developmental Cell.

Dr ...

New insights into salt transport in the kidney

2012-08-23

Sodium chloride, better known as salt, is vital for the organism, and the kidneys play a crucial role in the regulation of sodium balance. However, the underlying mechanisms of sodium balance are not yet completely understood. Researchers of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin-Buch, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the University of Kiel have now deciphered the function of a gene in the kidney and have thus gained new insights into this complex regulation process (PNAS Early Edition, doi/10.1073/pnas.1203834109)*.

In humans, the kidneys ...

Cloud control could tame hurricanes, study shows

2012-08-23

They are one of the most destructive forces of nature on Earth, but now environmental scientists are working to tame the hurricane. In a paper, published in Atmospheric Science Letters, the authors propose using cloud seeding to decrease sea surface temperatures where hurricanes form. Theoretically, the team claims the technique could reduce hurricane intensity by a category.

The team focused on the relationship between sea surface temperature and the energy associated with the destructive potential of hurricanes. Rather than seeding storm clouds or hurricanes directly, ...

Canadian researcher is on a mission to create an equal playing field at the Paralympic Games

2012-08-23

Vancouver, BC – August 23, 2012 – Vancouver-based clinician and researcher Dr. Andrei Krassioukov is packing for the upcoming Paralympic games in London. Rather than packing sports equipment, he has a suitcase full of advanced scientific equipment funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation that he will use to monitor the cardiovascular function of athletes with spinal cord injuries.

Up to 90% of people with injuries between that cervical and high thoracic vertebrae suffer from a condition that limits their ability to regulate heart rate and blood pressure. For top-level ...

Scientists produce H2 for fuel cells using an inexpensive catalyst under real-world conditions

2012-08-23

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have produced hydrogen, H2, a renewable energy source, from water using an inexpensive catalyst under industrially relevant conditions (using pH neutral water, surrounded by atmospheric oxygen, O2, and at room temperature).

Lead author of the research, Dr Erwin Reisner, an EPSRC research fellow and head of the Christian Doppler Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, said: "A H2 evolution catalyst which is active under elevated O2 levels is crucial if we are to develop an industrial water splitting process - a chemical reaction ...

1-molecule-thick material has big advantages

2012-08-23

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The discovery of graphene, a material just one atom thick and possessing exceptional strength and other novel properties, started an avalanche of research around its use for everything from electronics to optics to structural materials. But new research suggests that was just the beginning: A whole family of two-dimensional materials may open up even broader possibilities for applications that could change many aspects of modern life.

The latest "new" material, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) — which has actually been used for decades, but not in its 2-D ...

Is this real or just fantasy? ONR Augmented-Reality Initiative progresses

2012-08-23

ARLINGTON, Va.—The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is demonstrating the next phase of an augmented-reality project Aug. 23 in Princeton, N.J., that will change the way warfighters view operational environments—literally.

ONR has completed the first year of a multi-year augmented-reality effort, developing a system that allow trainees to view simulated images superimposed on real-world landscapes. One example of augmented reality technology can be seen in sports broadcasts, which use it to highlight first-down lines on football fields and animate hockey pucks to help TV ...

Spacetime: A smoother brew than we knew

2012-08-23

Spacetime may be less like beer and more like sipping whiskey.

Or so an intergalactic photo finish may suggest.

Physicist Robert Nemiroff of Michigan Technological University reached this heady conclusion after studying the tracings of three photons of differing wavelengths that were recorded by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope in May 2009.

The photons originated about 7 billion light years away from Earth in one of three pulses from a gamma-ray burst. They arrived at the orbiting telescope just one millisecond apart, in a virtual tie.

Gamma-ray bursts are ...

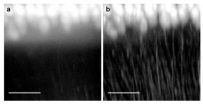

Novel microscopy method offers sharper view of brain's neural network

2012-08-23

WASHINGTON, Aug. 23—Shortly after the Hubble Space Telescope went into orbit in 1990 it was discovered that the craft had blurred vision. Fortunately, Space Shuttle astronauts were able to remedy the problem a few years later with supplemental optics. Now, a team of Italian researchers has performed a similar sight-correcting feat for a microscope imaging technique designed to explore a universe seemingly as vast as Hubble's but at the opposite end of the size spectrum—the neural pathways of the brain.

"Our system combines the best feature of one microscopy technique—high-speed, ...