(Press-News.org) A coral species that is found in abundance from Indonesia eastward to Fiji, Samoa, and the Line Islands rarely crosses the Eastern Pacific Barrier toward the coast of the Americas, according to a team of researchers led by Iliana Baums, an assistant professor of biology at Penn State University. Darwin hypothesized in 1880 that most species could not disperse across the marine barrier, and Baums's study is the first comprehensive test of that hypothesis using coral. The results of the scientific paper, which will be published in the journal Molecular Ecology, has important implications for climate-change research, species-preservation efforts, and the economic stability of the eastern Pacific region, including the Galapagos, Costa Rica, Panama, and Ecuador.

The Eastern Pacific Barrier (EPB) -- an uninterrupted 4,000-mile stretch of water with depths of up to 7 miles -- separates the central from the eastern Pacific Ocean. In his writings, Darwin had termed this barrier "impassable" and, since Darwin's time, scientists have confirmed that many species of marine animals cannot cross this oceanic divide. However, until now, researchers had not performed a comprehensive analysis of the impact of the barrier on coral species. "The adult colonies reproduce by making small coral larvae that stay in the water column for some time, where currents can take them to far-away places," Baums said. "But the EPB is a formidable barrier because the time it would take to cross it probably exceeds the life span of a larva."

To test whether or not coral larvae are able to travel across the barrier, Baums and her team chose a particularly hearty species called Porites lobata. "Compared with other coral species, Porites lobata larvae seem able to survive for longer periods of time; for example, the weeks that are required to travel across the marine barrier," Baums said. "This species also harbors symbionts in its larvae that can provide food during the long journey. In addition, the adults seem able to brave more extreme temperatures, as well as more acidic conditions. So, if any coral species is going to make it across, it is this one."

Baums and her team hypothesized that coral larvae originating in the central Pacific might be pushed along the North Equatorial Counter Current, which flows from west to east and becomes stronger and warmer in years with an El Niño Southern Oscillation event -- a climate pattern that occurs about every five years. "Coral larvae are not very mobile," Baums said. "So the only way coral larvae originating to the west of the barrier could travel to the east is along an ocean current, and warming of a current like the North Equatorial Counter Current would help larvae survive. If coral have traveled along this current in the past, we should find populations that are genetically similar living from the Galapagos to Costa Rica, Panama, and Ecuador."

The team members collected coral samples of the Porites lobata species from both sides of the Eastern Pacific Barrier and performed genetic tests using special markers called microsatellites -- repeating sequences of DNA that are informative for the purpose of distinguishing among individuals. "We found that Darwin was right: the EPB is a very effective barrier," Baums said. "For the most part, samples we found to the east are genetically dissimilar to those we found to the west. This means that coral larvae originating in the central Pacific simply are not making it across the ocean to the Americas."

The only exception, the team found, was a relatively small population of Porites lobata living near Clipperton Island, which is located just north and west of the Galapagos. The samples collected there were genetically similar to samples found throughout the central Pacific, indicating that the species had migrated there from the west relatively recently. "Interestingly, the coral that are lucky enough to cross the EPB to Clipperton Island stay there and don't go any farther," Baums explained. "In other words, we find that Porites lobata are not migrating south and east to the Galapagos after making it to Clipperton. We believe this is because these coral are adapted to the warmer conditions that their parents enjoyed to the west of the EPB; for example, near the Line Islands, Fiji, and Samoa. "Coral reefs thrive in shallow water in areas where the annual mean temperature is about 64 degrees Fahrenheit," Baums said. "The eastern Pacific tends to be much cooler; in part, because of a process called upwelling -- a phenomenon that occurs when winds stir up cold, deep ocean water, pulling it to the surface. Clipperton Island may provide a similar-enough environment to the Central Pacific, but the Galapagos area simply may be too cool."

The team's findings about the ability of coral to travel across the marine barrier have important implications for the economic stability of the eastern Pacific, the region's species-conservation efforts and, more broadly, for the impact of climate change on tropical ecosystems. The Galapagos, Costa Rica, Panama, and Ecuador all rely heavily on tourism. Tourism, in turn, relies on healthy reefs that divers can visit and the sale of shellfish and lobster -- species that are maintained, in large part, by the presence of coral communities.

"The take-home message is that coral populations in the eastern Pacific need to be protected," Baums said. "That is, in the event of any large-scale coral crisis, we cannot count on coral populations in the eastern Pacific being replenished by larvae from the west." Baums explained that, especially as the Earth's surface continues to warm, such a crisis to coral reefs is not unlikely. During the El Niño Southern Oscillation events that occurred from 1982 to 1983 and from 1997 to 1998, some of the reefs experienced a 90-percent loss. Although they ultimately were able to bounce back, a stronger El Niño event might spell extinction for some coral species.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Baums, other researchers who contributed to the study include Jennifer Boulay and Nicholas R. Polato at Penn State and Michael E. Hellberg at the Louisiana State University.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

CONTACTS

Iliana Baums: 814-867-0491, baums@psu.edu

Barbara Kennedy (PIO): 814-863-4682, science@psu.edu

IMAGE

High-resolution images associated with this research are online at http://www.science.psu.edu/news-and-events/2012-news/Baums8-2012.

GRANT NUMBERS

National Science Foundation (OCE- 0550294)

Darwin discovered to be right: Eastern Pacific barrier is virtually impassable by coral species

2012-08-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA infrared time series of Tropical Storm Isaac shows consolidation

2012-08-28

NASA's Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument is an infrared "eye" that flies onboard NASA's Aqua satellite. AIRS has been providing the National Hurricane Center with valuable temperature data on Isaac's clouds and the surrounding sea surface temperatures, and a time series of data shows that Isaac is consolidating.

The AIRS instrument has been monitoring Tropical Storm Isaac for several days. AIRS data from Aug. 24, 25, 26 and 27 showed Isaac's movements through the eastern and central Caribbean Sea, across eastern Cuba and into the Gulf of Mexico. On Aug. ...

Rising cardiovascular incidence after Japanese earthquake 2011

2012-08-28

Munich, Germany – August 27 2012: The Japanese earthquake and tsunami of 11 March 2011, which hit the north-east coast of Japan with a magnitude of 9.0 on the Richter scale, was one of the largest ocean-trench earthquakes ever recorded in Japan. The tsunami caused huge damage, including 15,861 dead and 3018 missing persons, and, as of 6 June 2012, 388,783 destroyed homes.

Following an investigation of the ambulance records made by doctors in the Miyagi prefecture, close to the epicentre of the earthquake and where the damage was greatest, cardiologist Dr Hiroaki Shimokawa ...

Panda preferences influence trees used for scent marking

2012-08-28

As solitary animals, giant pandas have developed a number of ways to communicate those times when they are ready to come into close contact. One means of this communication occurs through scent marking. A recent study by San Diego Zoo Global researchers, collaborating with researchers at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Science, indicates that pandas make clear and specific choices about what trees are used for scent marking.

"Variables affecting the selection of scent-marking sites included bark roughnesss, presence of moss on the tree trunk, tree diameter ...

Arctic sea ice shrinks to new low in satellite era

2012-08-28

The extent of the sea ice covering the Arctic Ocean has shrunk. According to scientists from NASA and the NASA-supported National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colo., the amount is the smallest size ever observed in the three decades since consistent satellite observations of the polar cap began.

The extent of Arctic sea ice on Aug. 26, as measured by the Special Sensor Microwave/Imager on the U.S. Defense Meteorological Satellite Program spacecraft and analyzed by NASA and NSIDC scientists, was 1.58 million square miles (4.10 million square kilometers), ...

WSU researcher documents links between nutrients, genes and cancer spread

2012-08-28

PULLMAN, Wash.—More than 40 plant-based compounds can turn on genes that slow the spread of cancer, according to a first-of-its-kind study by a Washington State University researcher.

Gary Meadows, WSU professor and associate dean for graduate education and scholarship in the College of Pharmacy, says he is encouraged by his findings because the spread of cancer is most often what makes the disease fatal. Moreover, says Meadows, diet, nutrients and plant-based chemicals appear to be opening many avenues of attack.

"We're always looking for a magic bullet," he says. "Well, ...

A greener way to fertilize nursery crops

2012-08-28

This press release is available in Spanish.

A U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientist has found a "green" alternative to a type of fertilizer additive that is believed to contribute to the accumulation of heavy metals in waterways.

Ornamental nursery and floral crops require micronutrients like iron, manganese, copper and zinc. But fertilizers that provide these micronutrients often include synthetically produced compounds that bind with the micronutrients so they are available in the root zone.

The most commonly used compounds, known as chelating agents, ...

George Washington University Computational Biology Director solves 200-year-old oceanic mystery

2012-08-28

WASHINGTON — The origin of Cerataspis monstrosa has been a mystery as deep as the ocean waters it hails from for more than 180 years. For nearly two centuries, researchers have tried to track down the larva that has shown up in the guts of other fish over time but found no adult counterpart. Until now.

George Washington University Biology Professor Keith Crandall cracked the code to the elusive crustacean's DNA this summer. His findings were recently published in the journal "Ecology and Evolution," and his research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the ...

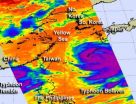

NASA sees Typhoon Bolaven dwarf Typhoon Tembin

2012-08-28

NASA satellites are providing imagery and data on Typhoon Tembin southwest of Taiwan, and Typhoon Bolaven is it barrels northwest through the Yellow Sea. In a stunning image from NASA's Aqua satellite, Bolaven appears twice as large as Tembin.

NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument that flies onboard the Terra satellite captured a remarkable image of Typhoon Tembin being dwarfed by giant Typhoon Bolaven at 0240 UTC on Aug. 27, 2012. The visible image shows that the island of Taiwan appears to be squeezed between the two typhoons, while ...

Plants unpack winter coats when days get shorter

2012-08-28

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Mechanisms that protect plants from freezing are placed in storage during the summer and wisely unpacked when days get shorter.

In the current issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Michael Thomashow, University Distinguished Professor of molecular genetics, demonstrates how the CBF (C-repeat binding factor) cold response pathway is inactive during warmer months when days are long, and how it's triggered by waning sunlight to prepare plants for freezing temperatures.

The CBF cold response pathway was discovered by Thomashow's ...

Parents and readers beware of stereotypes in young adult literature

2012-08-28

COLUMBIA, Mo. — A newly defined genre of literature, "teen sick-lit," features tear-jerking stories of ill adolescents developing romantic relationships. Although "teen sick-lit" tends to adhere to negative stereotypes of the ill and traditional gender roles, it also explores the taboo realm of sexuality, sickness and youth, says the University of Missouri researcher who named the genre in a recent study. Readers and their parents should be aware of how the presentation of disease and disability in these stories can instill prejudices and enforce societal norms in young ...