(Press-News.org) Biomembranes enclose biological cells like a skin. They also surround organelles that carry out important functions in metabolism and cell division. Scientists have long known in principle how biomembranes are built up, and also that water molecules play a role in maintaining the optimal distance between neighboring membranes—otherwise they could not fulfill their vital functions. Now, with the help of computer simulations, scientists of the Technische Universität München (TUM) and the Freie Universität Berlin have discovered two different mechanisms that prevent neighboring membrane surfaces from sticking together. Their results appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

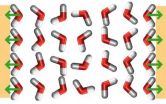

Biomembranes consist of lipids, chain-like fat molecules stacked side by side. In the aqueous environment of cells, the lipids organize themselves into a so-called bilayer with fat-soluble "hydrophobic" ends of the molecular chains facing inward and water-soluble "hydrophilic" ends facing outward. If the water-soluble surfaces of two membranes come too close to each other, a pressure is generated—hydration repulsion—that prevents the membrane surfaces from touching. Between two intact biomembranes there is always a film of water just a few nanometers thick. Until now, however, it was unclear how hydration repulsion works on the molecular level.

By means of complex simulations, the scientists discovered two different mechanisms whose contribution depends on the distance between the membranes. If the membranes are separated by around one nanometer or more, the water molecules play the decisive role in holding them apart. Since they have to orient themselves simultaneously to the lipids of both membrane surfaces, they give up their preferred spatial arrangement. Then they function like "bumpers," pushing the membranes apart. When the separation is smaller, the lipids in the opposing membrane surfaces mutually inhibit their own mobility, and the repulsive force is increased.

For some time, these two mechanisms had been discussed as possible explanations for hydration repulsion. Now, with their computer simulations, the scientists from TUM and FU Berlin have for the first time correctly predicted the strength of the pressure, that is, in agreement with experimental results. In doing so, they have elucidated in detail the significance of the different mechanisms. "We were able to predict the water pressure so accurately because we determined the chemical potential of the water precisely in our computations," explains Dr. Emanuel Schneck, formerly a member of the work group of FU Berlin Professor Roland Netz (then at TUM). Schneck is currently a researcher at the Institute Laue Langevin (ILL). "The chemical potential indicates how 'willing' the water molecules are to stay in a particular spot. In order for us to obtain correct results, the potential at the membrane surfaces and the potential in the surrounding water must have the same value in our simulations."

The researchers now want to translate their results to many more biological surfaces and, in the process, initiate considerably more complex computer models.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG SFB 765), and by the Ministry for Economy and Technology (BMWi) in an Allianz Industrie Forschung (AiF) project framework.

Original publication:

Hydration repulsion between biomembranes results from an interplay of dehydration and depolarization; Emanuel Schneck, Felix Sedlmeier and Roland R. Netz

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1205811109

Contact:

Dr. Emanuel Schneck

Institute Laue Langevin, Grenoble, Frankreich

Tel. +33476207622,

E-Mail: schnecke@ill.fr or emanuel.schneck@tum.de

Prof. Dr. Roland Netz

Fachbereich Physik der Freien Universität Berlin,

Tel.: 030 / 838-55737

E-Mail: rnetz@physik.fu-berlin.de

www.physik.fu-berlin.de/en/einrichtungen/ag/ag-netz/

Technische Universitaet Muenchen (TUM) is one of Europe's leading universities. It has roughly 480 professors, 9000 academic and non-academic staff, and 31,000 students. It focuses on the engineering sciences, natural sciences, life sciences, medicine, and economic sciences. After winning numerous awards, it was selected as an "Elite University" in 2006 and 2012 by the Science Council (Wissenschaftsrat) and the German Research Foundation (DFG). The university's global network includes an outpost with a research campus in Singapore. TUM is dedicated to the ideal of a top-level research-based entrepreneurial university. http://www.tum.de

Keep your distance! Why cells and organelles don't get stuck

Researchers explain 'hydration repulsion' between biomembranes

2012-08-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New DNA-method tracks fish and whales in seawater

2012-08-30

Danish researchers at University of Copenhagen lead the way for future monitoring of marine biodiversity and resources. By using DNA traces in seawater samples to keep track of fish and whales in the oceans. A half litre of seawater can contain evidence of local fish and whale faunas and combat traditional fishing methods. Their results are now published in the international scientific journal PLOS ONE.

"The new DNA-method means that we can keep better track of life beneath the surface of the oceans around the world, and better monitor and protect ocean biodiversity and ...

Yellowstone into the future

2012-08-30

Boulder, Colorado, USA – In the September issue of GSA TODAY Guillaume Girard and John Stix of McGill University in Montreal join the debate regarding future scenarios of intracaldera volcanism at Yellowstone National Park, USA.

Using data from quartz petrography, geochemistry, and geobarometry, Girard and Stix suggest that magma ascent during the most recent eruptions of intracaldera rhyolites occurred rapidly from depths of 8-10 km to the surface along major regional faults, without intervening storage. They consequently predict that future volcanism, which could include ...

State tax incentives do not appear to increase the rate of living organ donation

2012-08-30

The policies that several states have adopted giving tax deductions or credits to living organ donors do not appear to have increased donation rates. Authors of the study, appearing in the August issue of the American Journal of Transplantation, found little difference in the annual number of living organ donations per 100,000 population between the 15 states that had enacted some sort of tax benefit as of 2009 and states having no such policy at that time.

"There continue to be sizeable shortages in available organs for transplant, despite a number of interventions ...

Early menopause: A genetic mouse model of human primary ovarian insufficiency

2012-08-30

Scientists have established a genetic mouse model for primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), a human condition in which women experience irregular menstrual cycles and reduced fertility, and early exposure to estrogen deficiency.

POI affects approximately one in a hundred women. In most cases of primary ovarian insufficiency, the cause is mysterious, although genetics is known to play a causative role. There are no treatments designed to help preserve fertility. Some women with POI retain some ovarian function and a fraction (5-10 percent) have children after receiving ...

Possible therapy for tamoxifen resistant breast cancer identified

2012-08-30

The hormone estrogen stimulates the growth of breast cancers that are estrogen-receptor positive, the most common form of breast cancer.

The drug tamoxifen blocks this estrogen effect and prolongs the lives of, and helps to cure, patients with estrogen-sensitive breast cancer.

About 30 percent of these patients have tumors that are resistant to tamoxifen.

This study shows how these resistant tumors survive and grow, and it identifies an experimental agent that targets these breast cancers.

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A study by researchers at the Ohio State University Comprehensive ...

Study gives new insight on inflammation

2012-08-30

Scientists' discovery of an important step in the body's process for healing wounds may lead to a new way of treating inflammation.

A study published today in Current Biology details how an international team of researchers led by Monash University's Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute (ARMI) discovered the mechanism, which shuts down the signal triggering the body's initial inflammatory response to injury.

When the body suffers a wound or abrasion, white blood cells, or leukocytes, travel to the site of the injury to protect the tissue from infection and start ...

Protein impedes microcirculation of malaria-infected red blood cells

2012-08-30

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- When the parasite responsible for malaria infects human red blood cells, it launches a 48-hour remodeling of the host cells. During the first 24 hours of this cycle, a protein called RESA undertakes the first step of renovation: enhancing the stiffness of the cell membranes.

That increased rigidity impairs red blood cells' ability to travel through the blood vessels, especially at fever temperatures, according to a new study from researchers at MIT, the Institut Pasteur and the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).

This marks the ...

Many US schools are unprepared for another pandemic

2012-08-30

Washington, DC, August 30, 2012 – Less than half of U.S. schools address pandemic preparedness in their school plan, and only 40 percent have updated their school plan since the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, according to a study published in the September issue of the American Journal of Infection Control, the official publication of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

A team of researchers from Saint Louis University collected and analyzed survey responses from approximately 2,000 school nurses serving primarily elementary, middle, ...

Cancer 'turns off' important immune cells, complicating experimental vaccine therapies

2012-08-30

Bethesda, MD—A research report published in the September 2012 issue of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology offers a possible explanation of why some cancer vaccines are not as effective as hoped, while at the same time identifies a new therapeutic strategy for treating autoimmune problems. In the report, scientists suggest that cancer, even in the very early stages, produces a negative immune response from dendritic cells, which prevent lymphocytes from working against the disease. Although problematic for cancer treatment, these flawed dendritic cells could be valuable therapeutic ...

Millipede family added to Australian fauna

2012-08-30

An entire group of millipedes previously unknown in Australia has been discovered by a specialist – on museum shelves. Hundreds of tiny specimens of the widespread tropical family Pyrgodesmidae have been found among bulk samples in two museums, showing that native pyrgodesmids are not only widespread in Australia's tropical and subtropical forests, but are also abundant and diverse. The study has been published in the open access journal ZooKeys.

"Most pyrgodesmid species are so small they could be easily overlooked," explained millipede specialist Dr Robert Mesibov, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Keep your distance! Why cells and organelles don't get stuckResearchers explain 'hydration repulsion' between biomembranes