(Press-News.org) The Pink Double Dandy peony, the Double Peppermint petunia, the Doubled Strawberry Vanilla lily and nearly all roses are varieties cultivated for their double flowers.

The blossoms of these and other such plants are lush with extra petals in place of the parts of the flower needed for sexual reproduction and seed production, meaning double flowers – though beautiful – are mutants and usually sterile.

The genetic interruption that causes that mutation helped scientists in the 1990s pinpoint the genes responsible for normal development of sexual organs stamens and carpels in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, long used as a plant model by biologists.

Now for the first time, scientists have proved the same class of genes is at work in a representative of a more ancient plant lineage, offering a glimpse further back into the evolutionary development of flowers.

"It's pretty amazing that Arabidopsis and Thalictrum, the plant we studied, have genes that do the exact same kind of things in spite of the millions of years of evolution that separates the two species," said Verónica Di Stilio, University of Washington associate professor of biology. She is the corresponding author of a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The function of these organ-identity genes appears to be highly conserved according to the new research, meaning the gene is essential and its function has been maintained despite the formation of new species.

Identifying the genetic and biochemical basis of double flowering in Thalictrum suggests the class of genes that likely underlie other widespread double-flower varieties, according to Kelsey Galimba, a UW doctoral student in the Di Stilio lab and lead author of the paper.

"Growers might be interested that we've figured out what's going on genetically. In terms of applications, you could potentially trigger this if you were interested in creating double flowers because you know which gene to treat to get that flower form," Di Stilio said.

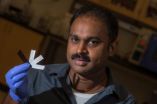

Di Stilio's group studied Thalictrum thalictroides. Known in the nursery trade as Anemonella thalictroides and rue anemone, the spring-flowering plant is native to the woods of Northeastern U.S. It belongs to the family Ranunculaceae, a sister lineage of the Eudicots. Eudicots today include 70 percent of all flowering species.

"The plants we've chosen to study possess ancestral floral traits and are sister to the core Eudicots that have model plants used by biologists such as Arabidopsis thaliana and Antirrhinum majus, or snapdragon," Di Stilio said. "But the plants in our study belong to a more ancient lineage. We're interested in evolution of flowers so we want to look at something that is a little bit different, that might inform us about how development has been tweaked over time to produce change."

The scientists compared the class of genes that direct the development of certain sexual reproduction organs in wild-type Thalictrum with that of the cultivated double-flower version known as Double White. In the mutant, Galimba spotted part of a transposon, jumping genes that can move about the organism's genome, sitting in the gene that affects development of reproductive organs. The protein produced by the mutant gene lacks some of the amino acids found in wild-type plants and the scientists hypothesize that it's not the right length to interact with other proteins normally, Galimba said.

The researchers then did a second check on the findings by using a technique called viral induced gene silencing to knock down the properly functioning gene in a wild-type plant. The resulting blossom looked very similar to the Double White mutant.

"The flower is one of the key innovations of flowering plants. It allowed flowering plants to coevolve with pollinators – mainly insects, but other animals as well – and use those pollinators for reproduction," Di Stilio said. "Many scientists are interested in finding the genetic underpinnings of flower diversification. Just how flowering plants become so species rich in such a relatively short period of geologic time has been a question since Darwin."

INFORMATION:

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation, including a research experience for undergraduate fellowship for co-author Theadora Tolkin, now a doctoral student at New York University. Other co-authors are Alessandra Sullivan, former Di Stilio lab member and current UW doctoral student; and collaborators Rainer Melzer and Günter Theiβen with Friedrich Schiller University in Germany.

For more information:

Di Stilio, 206 616-5567, distilio@uw.edu

Galimba, kgalimba@uw.edu, 206-685-4755

Suggested websites:

--Di Stilio

http://www.biology.washington.edu/users/ver%C3%B3nica-di-stilio

--Di Stilio lab

http://faculty.washington.edu/distilio/

--UW biology department

http://www.biology.washington.edu/

--Abstract of PNAS Plus paper

http://www.pnas.org/content/109/34/E2267.abstract

Gardener's delight offers glimpse into the evolution of flowering plants

2012-09-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pretreatment PET/CT imaging of lymph nodes predicts recurrence in breast cancer patients

2012-09-05

Disease-free survival for invasive ductal breast cancer (IDC) patients may be easier to predict with the help of F-18-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scans, according to research published in the September issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. New data show that high maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) of F-18-FDG in the lymph nodes prior to treatment could be an independent indicator of disease recurrence.

"Many studies have revealed that breast cancer patients with axillary lymph node metastasis have a significantly ...

Realizing the promise of RNA nanotechnology for new drug development

2012-09-05

New Rochelle, NY, September 4, 2012—The use of RNA in nanotechnology applications is highly promising for many applications, including the development of new therapeutic compounds. Key technical challenges remain, though, and the challenges and opportunities associated with the use of RNA molecules in nanotechnology approaches are presented in a review article in Nucleic Acid Therapeutics, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. The article is available free online at the Nucleic Acid Therapeutics website.

Peixuan Guo and colleagues, University of Kentucky, ...

Waste not, power up

2012-09-05

HOUSTON – (Sept. 4, 2012) – Researchers at Rice University and the Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium, have developed a way to make flexible components for rechargeable lithium-ion (LI) batteries from discarded silicon.

The Rice lab of materials scientist Pulickel Ajayan created forests of nanowires from high-value but hard-to-recycle silicon. Silicon absorbs 10 times more lithium than the carbon commonly used in LI batteries, but because it expands and contracts as it charges and discharges, it breaks down quickly.

The Ajayan lab reports this week in the journal ...

UCF researchers record world record laser pulse

2012-09-05

A University of Central Florida research team has created the world's shortest laser pulse and in the process may have given scientists a new tool to watch quantum mechanics in action – something that has been hidden from view until now.

UCF Professor Zenghu Chang from the Department of Physics and the College of Optics and Photonics, led the effort that generated a 67-attosecond pulse of extreme ultraviolet light. The results of his research are published online under Early Posting in the journal Optics Letters.

An attosecond is an incomprehensible quintillionith ...

Human impact felt on Black Sea long before industrial era

2012-09-05

When WHOI geologist Liviu Giosan first reconstructed the history of how the Danube River built its delta, he was presented with a puzzle.

In the delta's early stages of development, the river deposited its sediment within a protected bay. As the delta expanded onto the Black Sea shelf in the late Holocene and was exposed to greater waves and currents, rather than seeing the decline in sediment storage that he expected, Giosan found the opposite. The delta continued to grow. In fact, it has tripled its storage rate.

If an increase in river runoff was responsible for ...

U of M faculty find antimicrobials altering intestinal bacteria composition in swine

2012-09-05

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (09/04/2012) — Researchers from the University of Minnesota's College of Veterinary Medicine, concerned about the use of antibiotics in animal production, have found that antimicrobial growth promoters administered to swine can alter the kind of bacteria present in the animal's intestinal track, resulting in an accelerated rate of growth and development in the animals.

Antibiotics are routinely administered to swine to treat illness and to promote larger, leaner animals.

The results of the study, conducted by Richard Isaacson, Ph.D., microbiologist ...

Little evidence of health benefits from organic foods, Stanford study finds

2012-09-05

You're in the supermarket eyeing a basket of sweet, juicy plums. You reach for the conventionally grown stone fruit, then decide to spring the extra $1/pound for its organic cousin. You figure you've just made the healthier decision by choosing the organic product — but new findings from Stanford University cast some doubt on your thinking.

"There isn't much difference between organic and conventional foods, if you're an adult and making a decision based solely on your health," said Dena Bravata, MD, MS, the senior author of a paper comparing the nutrition of organic ...

Showing the way to improved water-splitting catalysts

2012-09-05

PASADENA, Calif.—Scientists and engineers around the world are working to find a way to power the planet using solar-powered fuel cells. Such green systems would split water during daylight hours, generating hydrogen (H2) that could then be stored and used later to produce water and electricity. But robust catalysts are needed to drive the water-splitting reaction. Platinum catalysts are quite good at this, but platinum is too rare and expensive to scale up for use worldwide. Several cobalt and nickel catalysts have been suggested as cheaper alternatives, but there is still ...

Repeated exposure to traumatic images may be harmful to health

2012-09-05

Irvine, Calif., Sept. 4, 2012 – Repeated exposure to violent images from the terrorist attacks of Sept ember 11 and the Iraq War led to an increase in physical and psychological ailments in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, according to a new UC Irvine study.

The study sheds light on the lingering effects of "collective traumas" such as natural disasters, mass shootings and terrorist attacks. A steady diet of graphic media images may have long-lasting mental and physical health consequences, says study author Roxane Cohen Silver, UCI professor of psychology ...

A blueprint for 'affective' aggression

2012-09-05

A North Carolina State University researcher has created a roadmap to areas of the brain associated with affective aggression in mice. This roadmap may be the first step toward finding therapies for humans suffering from affective aggression disorders that lead to impulsive violent acts.

Affective aggression differs from defensive aggression or premeditated aggression used by predators, in that the role of affective aggression isn't clear and could be considered maladaptive. NC State neurobiologist Dr. Troy Ghashghaei was interested in finding the areas of the brain engaged ...