(Press-News.org) A gene that may possibly belong to an entire new family of oncogenes has been linked by researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) to the resistance of breast cancer to a well-regarded and widely used cancer therapy.

One of the world's leading breast cancer researchers, Mina Bissell, Distinguished Scientist with Berkeley Lab's Life Sciences Division, led a study in which a protein known as FAM83A was linked to resistance to the cancer drugs known as EGFR-TKIs (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors). Not only may this discovery explain the clinical correlation between a high expression of FAM83A and a poor prognosis for breast cancer patients, it may also provide a new target for future therapies.

"Resistance to EGFR-TKIs has limited their use for breast cancer treatment and until now the mechanisms behind this resistance have largely been a mystery," Bissell says. "We've demonstrated, both in cultured cells and in mice, that FAM83A has oncogenic properties and when overexpressed in cancer cells confers EGFR-TKI resistance and promotes the proliferation and invasion of tumors."

Bissell is the corresponding author along with Saori Furuta, also with Berkeley Lab's Life Sciences Division, of a paper describing this research in the Journal of Clinical Investigation (JCI). The paper is titled "FAM83A confers EGFR-TKI resistance in breast cancer cells and in mice." Other co-authors are Sun-Young Lee, Roland Meier, Marc Lenburg, Paraic Kenny and Ren Xu.

Therapeutic targeting of oncogenes can be an effective way to fight some cancers as evidenced in the successful use of EGFR-TKIs to fight lung cancer. However, EGFR-TKIs have not been effective for treating breast cancers. EGFR-TKIs work by blocking EGFR from adding a phosphate molecule to downstream signaling proteins, an action called phosphorylation that is a necessary step in the development of many types of cancer.

"We hypothesized that resistance to EGFR-TKIs originated, at least in part, from molecular alterations that activated phosphorylation signaling downstream of EGFRs," Furuta says.

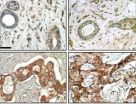

Using a unique three-dimensional cell culture assay based on phenotypic reversion that was originally developed by Bissell and her research group, the co-authors of the JCI paper screened for genes involved in EGFR-TKI resistance in both normal and cancerous human breast cell lines. They found that, while normal human breast tissue doesn't produce FAM38A, the protein is highly expressed in cancerous tissue. This was true for every breast cancer cell line they examined, and was particularly pronounced in those cell lines that have been the most resistant to treatment with EGFR-TKIs. Further studies showed that FAM83A interacts with and causes phosphorylation of critical signaling proteins downstream of EGFRs, as the researchers hypothesized. This downstream phosphorylation would act to blunt or negate any therapeutic effects of EGFR-TKIs that took place further upstream.

The results of this research are consistent with clinical data showing that breast cancer patients with high levels of FAM83A have a significantly lower survival rate than patients with low levels of FAM83A. However, while Bissell, Furuta and their colleagues note that a number of questions about FAM83A and other members of the FAM83 protein family remain to be addressed, the importance of these proteins as potential drug targets for therapy seems clear.

"The beauty of this study is that it not only helps explain why some breast cancer patients are resistant to EGFR-TKIs, but it also reveals a whole new family of potential oncogenes that could be a target for all types of cancer, including breast cancer," Bissell says.

Bissell says the results of this study also demonstrate the potential of using 3D phenotypic reversion assays as a new path to the discovery of more effective therapeutic drugs.

"Our 3D phenotypic reversion assay revealed the malignant phenotype, something that could not have been done with a 2D assay," she says. "This is the first time we have used our assay to discover a potential target for cancer drugs, but it shows that an assay like ours can be a powerful tool for finding new targets and therapies."

INFORMATION:

This research was primarily supported by the DOE Office of Science and the National Cancer Institute.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the Unites States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov.

Protein linked to therapy resistance in breast cancer

Berkeley lab researchers identify possible new oncogene and future therapy target

2012-09-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

What are the effects of the Great Recession on local governments?

2012-09-12

Freezing positions and cutting workforces

Trimming pension and health care costs and passing them to employees

Lowering service delivery levels, but not imposing many new fees

Using technology to reduce costs where possible

Receiving added pressure but little help from States and the Federal Government

This important new research sheds light on the challenges faced by city and county governments that must provide most basic services. Unlike federal or state governments, these local governments have limited ability to generate revenue and are often mandated to pay for ...

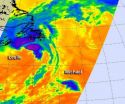

NASA infrared data reveals fading Tropical Storm Leslie and peanut-shaped Michael

2012-09-12

When NASA's Aqua satellite passed over the Atlantic on Sept. 11 it caught Tropical Storm Leslie's clouds over Newfoundland and peanut-shaped Tropical Storm Michael to its southwest. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument captured infrared data on Tropical Storms Leslie and Michael when it passed overhead on Sept. 11.

Michael Appears Peanut-Shaped on Satellite Imagery

Tropical Storm Michael forecast to become a remnant low later today, Sept. 11, but as of 11 a.m. EDT Michael still had maximum sustained winds near 45 mph (75 kmh). It was located about 1,090 ...

Yellow lights mean drivers have to make right choice -- if they have time

2012-09-12

A couple of years ago, Hesham Rakha misjudged a yellow traffic light and entered an intersection just as the light turned red. A police officer handed him a ticket.

"There are circumstances, as you approach a yellow light, where the decision is easy. If you are close to the intersection, you keep going. If you are far away, you stop. If you are almost at the intersection, you have to keep going because if you try to stop, you could cause a rear-end crash with the vehicle behind you and would be in the middle of the intersection anyway," said Rakha, professor of civil ...

Genetic make-up of children explains how they fight malaria infection

2012-09-12

Researchers from Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center and University of Montreal have identified several novel genes that make some children more efficient than others in the way their immune system responds to malaria infection. This world-first in integrative efforts to track down genes predisposing to specific immune responses to malaria and ultimately to identify the most suitable targets for vaccines or treatments was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by lead author Dr. Youssef Idaghdour and senior author Pr. Philip Awadalla, whose ...

Scientists discover how the brain ages

2012-09-12

The ageing process has its roots deep within the cells and molecules that make up our bodies. Experts have previously identified the molecular pathway that react to cell damage and stems the cell's ability to divide, known as cell senescence.

However, in cells that do not have this ability to divide, such as neurons in the brain and elsewhere, little was understood of the ageing process. Now a team of scientists at Newcastle University, led by Professor Thomas von Zglinicki have shown that these cells follow the same pathway.

This challenges previous assumptions ...

Uncertain about health outcomes, male stroke survivors more likely to suffer depression than females

2012-09-12

Philadelphia, PA, September 12, 2012 – Post-stroke depression is a major issue affecting approximately 33% of stroke survivors. A new study published in the current issue of Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation reports that the level to which survivors are uncertain about the outcome of their illness is strongly linked to depression. The relationship is more pronounced for men than for women.

"Male stroke survivors in the US who subscribe to traditional health-related beliefs may be accustomed to, and value highly, being in control of their health," says ...

Information theory helps unravel DNA's genetic code

2012-09-12

DNA consists of regions called exons, which code for the synthesis of proteins, interspersed with noncoding regions called introns. Being able to predict the different regions in a new and unannotated genome is one of the biggest challenges facing biologists today. Now researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi have used techniques from information theory to identify DNA introns and exons an order of magnitude faster than previously developed methods. The researchers were able to achieve this breakthrough in speed by looking at how electrical charges are ...

Going with the flow

2012-09-12

Scientists who study tissue engineering and test new drugs often need to sort, rotate, move, and otherwise manipulate individual cells. They can do this by prodding the cells into place with a mechanical probe or coaxing them in the desired direction with acoustic waves, electric fields, or flowing fluids. Techniques that rely on direct physical contact can position individual cells with a high level of precision while non-contact techniques are often faster for sorting large numbers of cells. An international team of researchers has now developed a way to manipulate cells ...

Less wear, longer life for memory storage device

2012-09-12

Probe storage devices read and write data by making nanoscale marks on a surface through physical contact. The technology may one day extend the data density limits of conventional magnetic and optical storage, but current probes have limited lifespans due to mechanical wear. A research team, led by Intel Corp., has now developed a long-lasting ultrahigh-density probe storage device by coating the tips of the probes with a thin metal film. The team's device features an array of 5,000 ultrasharp probes that is integrated with on-chip electronic circuits. The probes write ...

Weizmann Institute's mathematical model may lead to safer chemotherapy

2012-09-12

Cancer chemotherapy can be a life-saver, but it is fraught with severe side effects, among them an increased risk of infection. Until now, the major criterion for assessing this risk has been the blood cell count: if the number of white blood cells falls below a critical threshold, the risk of infection is thought to be high. A new model built by Weizmann Institute mathematicians in collaboration with physicians from the Meir Medical Center in Kfar Saba and from the Hoffmann-La Roche research center in Basel, Switzerland, suggests that for proper risk assessment, it is ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Protein linked to therapy resistance in breast cancerBerkeley lab researchers identify possible new oncogene and future therapy target