(Press-News.org) The most unambiguous data to date on the elusive 113th atomic element has been obtained by researchers at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Science (RNC). A chain of six consecutive alpha decays, produced in experiments at the RIKEN Radioisotope Beam Factory (RIBF), conclusively identifies the element through connections to well-known daughter nuclides. The groundbreaking result, reported in the Journal of Physical Society of Japan, sets the stage for Japan to claim naming rights for the element.

The search for superheavy elements is a difficult and painstaking process. Such elements do not occur in nature and must be produced through experiments involving nuclear reactors or particle accelerators, via processes of nuclear fusion or neutron absorption. Since the first such element was discovered in 1940, the United States, Russia and Germany have competed to synthesize more of them. Elements 93 to 103 were discovered by the Americans, elements 104 to 106 by the Russians and the Americans, elements 107 to 112 by the Germans, and the two most recently named elements, 114 and 116, by cooperative work of the Russians and Americans.

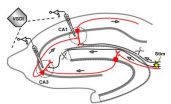

With their latest findings, associate chief scientist Kosuke Morita and his team at the RNC are set follow in these footsteps and make Japan the first country in Asia to name an atomic element. For many years Morita's team has conducted experiments at the RIKEN Linear Accelerator Facility in Wako, near Tokyo, in search of the element, using a custom-built gas-filled recoil ion separator (GARIS) coupled to a position-sensitive semiconductor detector to identify reaction products. On August 12, those experiments bore fruit: zinc ions travelling at 10% the speed of light collided with a thin bismuth layer to produce a very heavy ion followed by a chain of six consecutive alpha decays identified as products of an isotope of the 113th element (Figure 1).

While the team also detected element 113 in experiments conducted in 2004 and 2005, earlier results identified only four decay events followed by the spontaneous fission of dubnium-262 (element 105). In addition to spontaneous fission, the isotope dubnium-262 is known to also decay via alpha decay, but this was not observed, and naming rights were not granted since the final products were not well known nuclides at the time. The decay chain detected in the latest experiments, however, takes the alternative alpha decay route, with data indicating that dubnium decayed into lawrencium-258 (element 103) and finally into mendelevium-254 (element 101). The decay of dubnium-262 to lawrencium-258 is well known and provides unambiguous proof that element 113 is the origin of the chain.

Combined with their earlier experimental results, the team's groundbreaking discovery of the six-step alpha decay chain promises to clinch their claim to naming rights for the 113th element.

"For over 9 years, we have been searching for data conclusively identifying element 113, and now that at last we have it, it feels like a great weight has been lifted from our shoulders," Morita said. "I would like to thank all the researchers and staff involved in this momentous result, who persevered with the belief that one day, 113 would be ours. For our next challenge, we look to the uncharted territory of element 119 and beyond."

INFORMATION:

Reference

Kosuke Morita et al. "New Result in the Production and Decay of an Isotope, (278)113, of the 113th Element." Journal of Physical Society of Japan, 2012. DOI: 10.1143/JPSJ.81.103201

URL:

About RIKEN

RIKEN is Japan's flagship research institute devoted to basic and applied research. Over 2500 papers by RIKEN researchers are published every year in reputable scientific and technical journals, covering topics ranging across a broad spectrum of disciplines including physics, chemistry, biology, medical science and engineering. RIKEN's advanced research environment and strong emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration has earned itself an unparalleled reputation for scientific excellence in Japan and around the world.

About the Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Science

Named after the father of modern physics in Japan, Yoshio Nishina, the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science (RNC) carries on a long tradition of pioneering accelerator science, boasting the world's most powerful facilities for heavy ion physics. Since its inauguration in 2006, these facilities have drawn the attention of nuclear physicists around the globe with their promise to reveal a world of physics that exists only in the hottest stars, and in earliest stages of our universe.

Using its world class facilities, the RNC has set out to tackle two main goals: firstly, to greatly expand our knowledge of the nuclear world into regions of the nuclear chart presently beyond our grasp, and secondly, to apply this knowledge to other fields such as nuclear chemistry, bio and medical science, and materials science. Through international collaborations with researchers around the world, the center is uniquely positioned to succeed in achieving these goals in the years to come.

Reach us on Twitter: @rikenresearch

Search for element 113 concluded at last

After many years of painstaking work, Japanese researchers prove third time's a charm

2012-09-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers uncover biochemical events needed to maintain erection

2012-09-26

For two decades, scientists have known the biochemical factors that trigger penile erection, but not what's needed to maintain one. Now an article by Johns Hopkins researchers, scheduled to be published this week by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), uncovers the biochemical chain of events involved in that process. The information, they say, may lead to new therapies to help men who have erectile dysfunction.

"We've closed a gap in our knowledge," says Arthur Burnett, M.D., professor of urology at Johns Hopkins Medicine and the senior author ...

Moffitt Cancer Center researchers say smoking relapse prevention a healthy step for mothers, babies

2012-09-26

Researchers at Moffitt Cancer Center, concerned that women who quit smoking during their pregnancies often resume smoking after they deliver their baby, tested self-help interventions designed to prevent postpartum smoking relapse.

"We'd first like to see more women quit smoking when they become pregnant," said Thomas H. Brandon, Ph.D., senior member at Moffitt and chair of the Department of Health Outcomes and Behavior. "However, even among those who do quit, the majority return to smoking shortly after they give birth."

According to the researchers, nearly 50 percent ...

Severe hunger increases breast cancer risk in war survivors

2012-09-26

Jewish women who were severely exposed to hunger during World War Two were five times more likely to develop breast cancer than women who were mildly exposed, according to research in the October issue of IJCP, the International Journal of Clinical Practice.

The study also found that women who were up to seven-years-old during that period had a three times higher risk of developing breast cancer than women who were aged 14 years or over.

Sixty-five women diagnosed with breast cancer between 2005 and 2010 were compared with 200 controls without breast cancer. All ...

Slave rebellion is widespread in ants

2012-09-26

Ants that are held as slaves in nests of other ant species damage their oppressors through acts of sabotage. Ant researcher Professor Dr. Susanne Foitzik of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) in Germany first observed this "slave rebellion" phenomenon in 2009. According to the latest findings, however, this behavior now appears to be a widespread characteristic that is not limited to isolated occurrences. In fact, in three different populations in the U.S. states of West Virginia, New York, and Ohio, enslaved Temnothorax longispinosus workers have been observed to ...

Learning requires rhythmical activity of neurons

2012-09-26

This press release is available in German.

The hippocampus represents an important brain structure for learning. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich discovered how it filters electrical neuronal signals through an input and output control, thus regulating learning and memory processes. Accordingly, effective signal transmission needs so-called theta-frequency impulses of the cerebral cortex. With a frequency of three to eight hertz, these impulses generate waves of electrical activity that propagate through the hippocampus. Impulses of a different ...

New AACP Practice Parameter on gay, lesbian, bisexual, and gender variant issues

2012-09-26

Washington D.C., September 26, 2012 – The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) is proud to announce its new Practice Parameter on issues related to and affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual, and gender variant youth.

Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and gender variant children and adolescents face unique developmental challenges and stressors that can influence their mental health and wellbeing. Social issues such as stigma, bullying, and discrimination, and personal factors like internalized prejudice and feelings of being different are just a few of the concerns ...

Melatonin and exercise work against Alzheimer's in mice

2012-09-26

The combination of two neuroprotective therapies, voluntary physical exercise, and the daily intake of melatonin has been shown to have a synergistic effect against brain deterioration in rodents with three different mutations of Alzheimer's disease.

A study carried out by a group of researchers from the Barcelona Biomedical Research Institute (IIBB), in collaboration with the University of Granada and the Autonomous University of Barcelona, shows the combined effect of neuroprotective therapies against Alzheimer's in mice.

Daily voluntary exercise and daily intake ...

New simulation method produces realistic fluid movements

2012-09-26

What does a yoghurt look like over time? The food industry will soon be able to answer this question using a new fluid simulation tool developed by the Department of Computer Science (DIKU) at the University of Copenhagen as part of a broad partnership with other research institutions. An epoch-making shift in the way we simulate the physical world is now a reality.

A five-year collaboration between the University of Copenhagen, the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) and the Alexandra Institute on simulating fluids in movement is now bearing fruit, and has earned the ...

How is a Kindle like a cuttlefish

2012-09-26

Over millions of years, biological organisms – from the chameleon and cuttlefish to the octopus and squid – have developed color-changing abilities for adaptive concealment (e.g., camouflage) and communication signaling (e.g., warning or mating cues).

Over the past two decades, humans have begun to develop sophisticated e-Paper technology in electronic devices that reflect and draw upon the ambient light around you to create multiple colors, contrast and diffusion to communicate text and images.

And given the more than 100 million years head start that evolution has ...

Reducing acrylamide levels in french fries

2012-09-26

The process for preparing frozen, par-fried potato strips — distributed to some food outlets for making french fries — can influence the formation of acrylamide in the fries that people eat, a new study has found. Published in ACS' Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, the study identifies potential ways of reducing levels of acrylamide, which the National Toxicology Program and the International Agency for Research on Cancer regard as a "probable human carcinogen."

Acrylamide forms naturally during the cooking of many food products. Donald S. Mottram and colleagues ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

Modified biochar helps compost retain nitrogen and build richer soil organic matter

First gene regulation clinical trials for epilepsy show promising results

Life-changing drug identified for children with rare epilepsy

Husker researchers collaborate to explore fear of spiders

Mayo Clinic researchers discover hidden brain map that may improve epilepsy care

NYCST announces Round 2 Awards for space technology projects

How the Dobbs decision and abortion restrictions changed where medical students apply to residency programs

Microwave frying can help lower oil content for healthier French fries

In MS, wearable sensors may help identify people at risk of worsening disability

Study: Football associated with nearly one in five brain injuries in youth sports

Machine-learning immune-system analysis study may hold clues to personalized medicine

A promising potential therapeutic strategy for Rett syndrome

How time changes impact public sentiment in the U.S.

Analysis of charred food in pot reveals that prehistoric Europeans had surprisingly complex cuisines

[Press-News.org] Search for element 113 concluded at lastAfter many years of painstaking work, Japanese researchers prove third time's a charm