(Press-News.org) A new scientific report out today from the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene (IFH) dismantles the myth that the epidemic rise in allergies in recent years has happened because we're living in sterile homes and overdoing hygiene.

But far from saying microbial exposure is not important, the report concludes that losing touch with microbial 'old friends' may be a fundamental factor underlying rises in an even wider array of serious diseases. As well as allergies, there are numerous other 'chronic inflammatory diseases' (CIDs) such as Type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis which seem to stem from impaired regulation of our immune systems. Deficiencies in microbial exposure could be key to rises in both allergies and CIDs.

This detailed review of evidence, accumulated over more than 20 years of research since the 'hygiene hypothesis' was first proposed, now confirms that the original notion is not correct.

Presenting the report findings in Liverpool today at Infection Prevention 2012, the national conference of the UK and Ireland's Infection Prevention Society, co-author of the report and Honorary Professor at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Professor Sally Bloomfield explains: "The underlying idea that microbial exposure is crucial to regulating the immune system is right. But the idea that children who have fewer infections, because of more hygienic homes, are then more likely to develop asthma and other allergies does not hold up."

Another author of the report, Dr Rosalind Stanwell-Smith, also from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said: "Allergies and chronic inflammatory diseases are serious health issues and it's time we recognised that simplistically talking about home and personal cleanliness as the cause of the problem is ill-advised, because it's diverting attention from finding workable solutions and the true, probably much more complex, causes." If worrying about 'being too clean' results in people needlessly exposing themselves and their children to pathogens that can make them ill, this would clearly be dangerous.

Professor Graham Rook, also co-author of the report, who developed the 'Old Friends' version of the hypothesis, said: "The rise in allergies and inflammatory diseases seems at least partly due to gradually losing contact with the range of microbes our immune systems evolved with, way back in the Stone Age. Only now are we seeing the consequences of this, doubtless also driven by genetic predisposition and a range of factors in our modern lifestyle - from different diets and pollution to stress and inactivity. It seems that some people now have inadequately regulated immune systems that are less able to cope with these other factors."

Dr Stanwell Smith explains the probable reasons why this has happened "since the 1800s, when allergies began to be more noticed, the mix of microbes we've lived with, and eaten, drunk and breathed in has been steadily changing. Some of this has come through measures to combat infectious diseases that used to take such a heavy toll in those days - in London, 1 in 3 deaths was a child under 5. These changes include clean drinking water, safe food, sanitation and sewers, and maybe overuse of antibiotics. Whilst vital for protecting us from infectious diseases, these will also have inadvertently altered exposure to the 'microbial friends' which inhabit the same environments".

But we've also lost touch with our "old friends" in other ways: our modern homes have a different and less diverse mix of microbes than rural homes of the past. This is nothing to do with cleaning habits: even the cleanest-looking homes still abound with bacteria, viruses, fungi, moulds and dust mites. It's mainly because microbes come in from outside and the microbes in towns and cities are very different from those on farms and in the countryside.

"The good news", says Professor Bloomfield "is that we aren't faced with a stark choice between running the risk of infectious disease, or suffering allergies and inflammatory diseases. The threat of infectious disease is now rising because of antibiotic resistance, global mobility and an ageing population, so good hygiene is even more vital to all of us."

"How we can begin to reverse the trend in allergies and CID isn't yet clear", says Professor Rook. "There are lots of ideas being explored but relaxing hygiene won't reunite us with our Old Friends - just expose us to new enemies like E. coli O104."

"One important thing we can do", says Professor Bloomfield, "is to stop talking about 'being too clean' and get people thinking about how we can safely reconnect with the right kind of dirt".

###

Notes to Editors:

A pdf file of the full report is available for downloading from http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/IntegratedCRD.nsf/a639aacb2d462a2180257506004d35db/00bf50c9379c013c80257a7f0043aaa2?OpenDocument

IFH has also produced a short summary of the findings and conclusions from the report. This is available in hard copy and also to download from from http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/IntegratedCRD.nsf/a639aacb2d462a2180257506004d35db/c759d5e11822c33980257a7d0050f8fb?OpenDocument

IFH has also produced a general fact sheet and Q and A sheet on issues related to immunity to infectious disease, allergies and the hygiene hypothesis which are available from www.ifh-homehygiene.org

For media enquiries, or to arrange an interview, please contact: sallyfbloomfield@aol.com, tel. mobile 0791 9554781

Allergy rises not down to being too clean, just losing touch with 'old friends'

2012-10-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A mammal lung, in 3-D

2012-10-03

VIDEO:

The video shows the imaging of a section of a mouse lung. As the image rotates, more respiratory branches (bronchioles) are shown, along with three acini (yellow, green and orange...

Click here for more information.

Amidst the extraordinarily dense network of pathways in a mammal lung is a common destination. There, any road leads to a cul-de-sac of sorts called the pulmonary acinus. This place looks like a bunch of grapes attached to a stem (acinus means "berry" ...

University of Alberta has $12.3-billion impact on Alberta economy

2012-10-03

(Edmonton) The University of Alberta's impact on the Alberta economy is estimated to be $12.3 billion, which is five per cent of the province's gross domestic product—or the equivalent of having 135 Edmonton Oilers NHL teams in Alberta, according to a new study.

"When a university educates a population, it's the whole region that benefits," said study co-author Anthony Briggs, an assistant professor in the Alberta School of Business at the U of A. "We're not looking at the cost of the education and research, which is just one slice, but estimating the value of the investment. ...

Visionary transparent memory a step closer to reality

2012-10-03

HOUSTON – (Oct. 2, 2012) – Researchers at Rice University are designing transparent, two-terminal, three-dimensional computer memories on flexible sheets that show promise for electronics and sophisticated heads-up displays.

The technique based on the switching properties of silicon oxide, a breakthrough discovery by Rice in 2008, was reported today in the online journal Nature Communications.

The Rice team led by chemist James Tour and physicist Douglas Natelson is making highly transparent, nonvolatile resistive memory devices based on the revelation that silicon ...

Starting antiretroviral therapy improves HIV-infected Africans' nutrition

2012-10-03

Starting HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy reduces food insecurity and improves physical health, thereby contributing to the disruption of a lethal syndemic, UCSF and Massachusetts General Hospital researchers have found in a study focused on sub-Saharan Africa.

The study was published this week in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes.

With more than 20 million people infected with HIV/AIDS and almost 240 million people lacking access to enough food, sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing co-epidemics of food insecurity and HIV/AIDS that intensify ...

For elephants, deciding to leave watering hole demands conversation, Stanford study shows

2012-10-03

STANFORD, Calif. — In the wilds of Africa, when it's time for a family of elephants gathered at a watering hole to leave, the matriarch of the group gives the "let's-go rumble" — as it's referred to in scientific literature — kicking off a coordinated and well-timed conversation, of sorts, between the leaders of the clan.

First, the head honcho moves away from the group, turns her back and gives a long, slightly modulated and — to human ears — soft rumble while steadily flapping her ears. This spurs a series of back and forth vocalizations, or rumbles, within the group ...

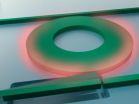

University of Minnesota engineers invent new device that could increase Internet download speeds

2012-10-03

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (10/02/2012) —A team of scientists and engineers at the University of Minnesota has invented a unique microscale optical device that could greatly increase the speed of downloading information online and reduce the cost of Internet transmission.

The device uses the force generated by light to flop a mechanical switch of light on and off at a very high speed. This development could lead to advances in computation and signal processing using light instead of electrical current with higher performance and lower power consumption.

The research results ...

1 glue, 2 functions

2012-10-03

Akron, Ohio, Oct. 2, 2012 — While the common house spider may be creepy, it also has been inspiring researchers to find new and better ways to develop adhesives for human applications such as wound healing and industrial-strength tape. Think about an adhesive suture strong enough to heal a fractured shoulder and that same adhesive designed with a light tackiness ideal for "ouch-free" bandages.

University of Akron polymer scientists and biologists have discovered that this house spider — in order to more efficiently capture different types of prey — performs an uncommon ...

Too little nitrogen may restrain plants' carbon storage capability, U of M paper shows

2012-10-03

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (10/02/2012) —Plants' ability to absorb increased levels of carbon dioxide in the air may have been overestimated, a new University of Minnesota study shows.

The study, published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change, shows that even though plants absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide and actually can benefit from higher levels of it, they may not get enough of the nutrients they need from typical soils to absorb as much CO2 as scientists had previously estimated. Carbon dioxide absorption is an important factor in mitigating fossil-fuel ...

Acoustic cell-sorting chip may lead to cell phone-sized medical labs

2012-10-03

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- A technique that uses acoustic waves to sort cells on a chip may create miniature medical analytic devices that could make Star Trek's tricorder seem a bit bulky in comparison, according to a team of researchers.

The device uses two beams of acoustic -- or sound -- waves to act as acoustic tweezers and sort a continuous flow of cells on a dime-sized chip, said Tony Jun Huang, associate professor of engineering science and mechanics, Penn State. By changing the frequency of the acoustic waves, researchers can easily alter the paths of the cells.

Huang ...

Payoff lacking for casino comps

2012-10-03

A study of widely used complimentary offers at Atlantic City casinos finds that common giveaways such as free rooms and dining credits are less profitable – and lead to unhealthy competition among casinos – than alternative comps such as free travel and parking.

The research, co-authored by Seul Ki Lee, an assistant professor at Temple University's School of Tourism and Hospitality Management, analyzed monthly promotional allowance and expenditure data from 11 casinos in the Atlantic City market from 2008 to 2010. Atlantic City is the second largest gaming market in ...