(Press-News.org) A study in the current issue of Scientific Reports, a new online journal from the Nature Publishing Group, shows that small forage fish like anchovies can play an important role in the "biological pump," the process by which marine life transports carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and surface ocean into the deep sea—where it contributes nothing to current global warming.

The study, by Dr. Grace Saba of Rutgers University and professor Deborah Steinberg of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, reports on data collected during an oceanographic expedition to the California coast during Saba's graduate studies at VIMS. Saba, now a post-doctoral researcher in Rutgers' Institute of Marine and Coastal Research, earned her Ph.D. from the College of William and Mary's School of Marine Science at VIMS in 2009. The expedition, aboard the research vessel Point Sur, was funded by the National Science Foundation.

The study's focus on fish is a departure for Steinberg and colleagues in her Zooplankton Ecology Lab, who typically study tiny crustaceans called copepods. Research by Steinberg's team during the last two decades has revealed that copepods and other small, drifting marine animals play a key role in the biological pump by grazing on photosynthetic algae near the sea surface, then releasing the carbon they've ingested as "fecal pellets" that can rapidly sink to the deep ocean. The algal cells are themselves generally too small and light to sink.

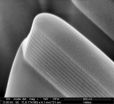

"'Fecal pellet' is the scientific term for "poop," laughs Steinberg. "Previous studies in our lab and by other researchers show that zooplankton fecal pellets can sink at rates of hundreds to thousands of feet per day, providing an efficient means of moving carbon to depth. But there have been few studies of fecal pellets from fish, thus the impetus for our project."

Saba says, "We collected fecal pellets produced by northern anchovies, a forage fish, in the Santa Barbara Channel off the coast of southern California." She determined that sinking rates for the anchovies' fecal pellets average around 2,500 feet per day, extrapolating from the time required for pellets to descend through a cylinder of water during experiments in the shipboard lab.

At that rate, says Saba, "pellets produced at the surface would travel the 1,600 feet to the seafloor at our study site in less than a day."

Saba and Steinberg also counted the pellets' abundance—up to 6 per cubic meter of seawater, measured their carbon content—an average of 22 micrograms per pellet, and painstakingly identified their partly digested contents—mostly single-celled algae like dinoflagellates and diatoms.

"Twenty micrograms of carbon might not seem like much," says Steinberg, "but when you multiply that by the high numbers of forage fish and fecal pellets that can occur within nutrient-rich coastal zones, the numbers can really add up."

Saba and Steinberg calculate that the total "downward flux" of carbon within fish fecal pellets at their study site reached a maximum of 251 milligrams per square meter per day—equal to or greater than previously measured values of sinking organic matter collected by suspended "sediment traps."

"Our findings show that—given the right conditions—fish fecal pellets can transport significant amounts of repackaged surface material to depth, and do so relatively quickly," says Saba.

Those conditions are likely to occur in places like the western coasts of North and South America, where ocean currents impinge on continental shelves, bringing cold, nutrient-rich waters from depth into the sunlit surface zone.

INFORMATION:

Study shows small fish can play a big role in coastal carbon cycle

2012-10-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Applying information theory to linguistics

2012-10-10

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- The majority of languages — roughly 85 percent of them — can be sorted into two categories: those, like English, in which the basic sentence form is subject-verb-object ("the girl kicks the ball"), and those, like Japanese, in which the basic sentence form is subject-object-verb ("the girl the ball kicks").

The reason for the difference has remained somewhat mysterious, but researchers from MIT's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences now believe that they can account for it using concepts borrowed from information theory, the discipline, invented ...

A problem shared is a problem halved

2012-10-10

The experience of being bullied is particularly detrimental to the psychological health of school girls who don't have social support from either adults or peers, according to a new study by Dr. Martin Guhn and colleagues from the University of British Columbia in Canada. In contrast, social support from adults or peers (or both) appears to lessen the negative consequences of bullying in this group, namely anxiety and depression. The work is published online in Springer's Journal of Happiness Studies.

Guhn and his team looked at whether the combination of high levels ...

Research reveals more about spatial memory problems associated with Alzheimer's

2012-10-10

Researchers at Western University have created a mouse model that reproduces some of the chemical changes in the brain that occur with Alzheimer's, shedding new light on this devastating disease. Marco Prado, Vania Prado and their colleagues at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry's Robarts Research Institute, looked at changes related to a neurotransmitter or chemical messenger, named acetylcholine (ACh), and the kinds of memory problems associated with it. The research is now published online by PNAS.

The researchers, including first author Amanda Martyn, ...

Photonic gels are colorful sensors

2012-10-10

HOUSTON – (Oct. 10, 2012) – Materials scientists at Rice University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have created very thin color-changing films that may serve as part of inexpensive sensors for food spoilage or security, multiband optical elements in laser-driven systems and even as part of high-contrast displays.

The new work led by Rice materials scientist Ned Thomas combines polymers into a unique, self-assembled metamaterial that, when exposed to ions in a solution or in the environment, changes color depending on the ions' ability to infiltrate ...

Criteria used to diagnose sports head injuries found to be inconsistent

2012-10-10

In recent years it has become clear that athletes who experience repeated impacts to the head may be at risk of potentially serious neurological and psychiatric problems. But a study of sports programs at three major universities, published in the October 2 Journal of Neurosurgery, finds that the way the injury commonly called concussion is usually diagnosed – largely based on athletes' subjective symptoms – varies greatly and may not be the best way to determine who is at risk for future problems. In addition, the way the term concussion is used in sports injuries may ...

High toll of mental illness and addictions must be addressed

2012-10-10

October 10, 2012 (Toronto) – Mental illnesses and addictions take more of a toll on the health of Ontarians than cancer or infectious diseases, according to a new report by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and Public Health Ontario – yet this burden could be reduced with treatment, say scientists from Canada's Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

"The majority of people with mental illness or addiction aren't receiving treatment, even though effective interventions are available," says report co-author Dr. Paul Kurdyak, Chief of General and Health ...

RNA-based therapy brings new hope for an incurable blood cancer

2012-10-10

Three thousand new cases of Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), a form of blood cancer, appear in the United States each year. With a median survival span of only five to seven years, according to the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, this disease is devastating, and new therapies are sorely needed.

One of the characteristics that defines MCL is heightened activity in the gene CCND1, which leads to the aggressive over-production of Cyclin D1, a protein that controls the proliferation of cells, explains Prof. Dan Peer of Tel Aviv University's Department of Cell Research and Immunology. ...

Squeezing ovarian cancer cells to predict metastatic potential

2012-10-10

New Georgia Tech research shows that cell stiffness could be a valuable clue for doctors as they search for and treat cancerous cells before they're able to spread. The findings, which are published in the journal PLoS One, found that highly metastatic ovarian cancer cells are several times softer than less metastatic ovarian cancer cells.

Assistant Professor Todd Sulchek and Ph.D. student Wenwei Xu used a process called atomic force microscopy (AFM) to study the mechanical properties of various ovarian cell lines. A soft mechanical probe "tapped" healthy, malignant and ...

Effectiveness of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in Peru

2012-10-10

In this week's PLOS Medicine, Anna Borquez from Imperial College London and an international group of authors developed a mathematical model representing the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transwomen in Lima, Peru as a test-case for the effectiveness of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The model was used to investigate the population-level impact, cost, and cost-effectiveness of PrEP under a range of different scenarios. The authors found that strategic PrEP intervention could be a cost-effective addition to existing HIV prevention strategies ...

Most pregnancy-related infections are caused by four treatable conditions

2012-10-10

In low-and-middle income countries, pregnancy-related infections are a major cause of maternal death, can also be fatal to unborn and newborn babies, and are mostly caused by four types of conditions that are treatable and preventable, according to a review by US researchers published in this week's PLOS Medicine.

The authors, led by Michael Gravett and a team of investigators from the University of Washington in Seattle, PATH (Program for Appropriate Technology in Health), and GAPPS (Global Alliance to Prevent Prematurity and Stillbirth, Seattle Children's) reviewed ...