(Press-News.org) At very low temperatures, close to absolute zero, chemical reactions may proceed at a much higher rate than classical chemistry says they should – because in this extreme chill, quantum effects enter the picture. A Weizmann Institute team has now confirmed this experimentally; their results would not only provide insight into processes in the intriguing quantum world in which particles act as waves, it might explain how chemical reactions occur in the vast frigid regions of interstellar space.

Long-standing predictions are that quantum effects should allow the formation of a transient bond – one that will force colliding atoms and molecules to orbit each other, instead of separating after the collision. Such a state would be very important, as orbiting atoms and molecules could have multiple chances to interact chemically. In this theory, a reaction that would seem to have a very low probability of occurring would proceed very rapidly at certain energies.

Dr. Ed Narevicius and his team in the Institute's Chemical Physics Department managed, for the first time, to experimentally confirm this elusive process in a reaction they performed at chilling temperatures of just a fraction of a degree above the absolute zero – 0.01°K. Their results appeared this week in Science.

"The problem," says Narevicius, "is that in classical chemistry, we think of reactions in terms of colliding billiard balls held together by springs on the molecular level. In the classical picture, reaction barriers block those billiard balls from approaching one another, whereas in the quantum physics world, reaction barriers can be penetrated by particles, as these acquire wave-like qualities at ultra-low temperatures."

The quest to observe quantum effects in chemical reactions started over half a century ago with pioneering experiments by Dudley Herschbach and Yuan T. Lee, who later received a Nobel Prize for their work. They succeeded in observing chemical reactions at unprecedented resolution by colliding two low-temperature, supersonic beams. However, the collisions took place at relative speeds that were much too high to resolve many quantum effects: When two fast beams collide, the relative velocity sets the collision temperature at above 100°K, much too warm for quantum effects to play a significant role. Over the years, researchers had used various ingenious techniques, including changing the angle of the beams and slowing them down to a near-halt. These managed to bring the temperatures down to around 5°K – close, but still a miss for those seeking to observe chemical reactions in quantum conditions.

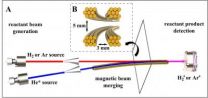

The innovation that Narevicius and his team, including Alon B. Henson, Sasha Gersten, Yuval Shagam and Julia Narevicius, introduced was to merge the beams rather than collide them. One beam was produced in a straight line, and the second beam was bent using a magnetic device until it was parallel with the first. Even though the beams were racing at high-speed, the relative speed of the particles in relation to the others was zero. Thus a much lower collision temperature of only 0.01 K could be achieved. One beam contained helium atoms in an excited state, the other either argon atoms or hydrogen molecules. In the ensuing chemical reaction, the argon or hydrogen molecules became ionized – releasing electrons.

To see if quantum phenomena were in play, the researchers looked at reaction rates – a measure of how fast a reaction proceeds – at different collision energies. At high collision energies, classical effects dominated and the reaction rates slowed down gradually as the temperature dropped. But below about 3°K, the reaction rate in the merged beams suddenly took on peaks and valleys. This is a sign that a quantum phenomenon known as scattering resonances due to tunneling was occurring in the reactions. At low energies, particles started behaving as waves: Those waves that were able to tunnel through the potential barrier interfered constructively with the reflected waves upon collision. This creates a standing wave that corresponds to particles trapped in orbits around one another. Such interference occurs at particular energies and is marked by a dramatic increase in reaction rates.

Narevicius: "Our experiment is the first proof that the reaction rate can change dramatically in the cold reaction regime. Beyond the surprising results, we have shown that such measurements can serve as an ultrasensitive probe for reaction dynamics. Our observations already prove that our understanding of even the simplest ionization reaction is far from complete; it requires a thorough rethinking and the construction of better theoretical models. We expect that our method will be used to solve many puzzles in reactions that are especially relevant to interstellar chemistry, which generally occurs at ultra-low temperatures."

INFORMATION:

Dr. Edvardas Narevicius is the incumbent of the Ernst and Kaethe Ascher Career Development Chair.

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, is one of the world's top-ranking multidisciplinary research institutions. Noted for its wide-ranging exploration of the natural and exact sciences, the Institute is home to 2,700 scientists, students, technicians and supporting staff. Institute research efforts include the search for new ways of fighting disease and hunger, examining leading questions in mathematics and computer science, probing the physics of matter and the universe, creating novel materials and developing new strategies for protecting the environment.

Weizmann Institute news releases are posted on the World Wide Web at http://wiswander.weizmann.ac.il/, and are also available at http://www.eurekalert.org/

Weizmann Institute Scientists observe quantum effects in cold chemistry

2012-10-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Developmental biologist proposes new theory of early animal evolution

2012-10-12

VALHALLA, October 11, 2012—A New York Medical College developmental biologist whose life's work has supported the theory of evolution has developed a concept that dramatically alters one of its basic assumptions—that survival is based on a change's functional advantage if it is to persist. Stuart A. Newman, Ph.D., professor of cell biology and anatomy, offers an alternative model in proposing that the origination of the structural motifs of animal form were actually predictable and relatively sudden, with abrupt morphological transformations favored during the early period ...

Alzheimer's sufferers may function better with less visual clutter

2012-10-12

TORONTO, ON – Psychologists at the University of Toronto and the Georgia Institute of Technology – commonly known as Georgia Tech – have shown that an individual's inability to recognize once-familiar faces and objects may have as much to do with difficulty perceiving their distinct features as it does with the capacity to recall from memory.

A study published in the October issue of Hippocampus suggests that memory impairments for people diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer's disease may in part be due to problems with determining the differences between similar objects. ...

Exercise helps ease premature cardiovascular aging caused by type 2 diabetes

2012-10-12

WESTMINSTER, CO (October 10, 2012)—One of life's certainties is that everyone ages. However, it's also certain that not everyone ages at the same rate. According to recent research being presented this week, the cardiovascular system of people with type 2 diabetes shows signs of aging significantly earlier than those without the disease. However, exercise can help to slow down this premature aging, bringing the aging of type 2 diabetes patients' cardiovascular systems closer to that of people without the disease, says researcher Amy Huebschmann of the University of Colorado ...

Exercise could fortify immune system against future cancers

2012-10-12

WESTMINSTER, CO (October 10, 2012)—Researchers may soon be able to add yet another item to the list of exercise's well-documented health benefits: A preliminary study suggests that when cancer survivors exercise for several weeks after they finish chemotherapy, their immune systems remodel themselves to become more effective, potentially fending off future incidences of cancer. The finding may help explain why exercise can significantly reduce the chances of secondary cancers in survivors or reduce the chances of cancer altogether in people who have never had the disease.

Laura ...

Parental bonding makes for happy, stable child

2012-10-12

Parents: Want to help ensure your children turn out to be happy and socially well adjusted? Bond with them when they are infants.

That's the message from a study by the University of Iowa, which found that infants who have a close, intimate relationship with a parent are less likely to be troubled, aggressive or experience other emotional and behavioral problems when they reach school age. Surprisingly, the researchers found that a young child needs to feel particularly secure with only one parent to reap the benefits of stable emotions and behavior, and that being attached ...

Minutes of hard exercise can lead to all-day calorie burn

2012-10-12

WESTMINSTER, CO (October 10, 2012)—Time spent in the drudgery of strenuous exercise is a well-documented turn-off for many people who want to get in better shape. In a new study, researchers show that exercisers can burn as many as 200 extra calories in as little as 2.5 minutes of concentrated effort a day—as long as they intersperse longer periods of easy recovery in a practice known as sprint interval training. The finding could make exercise more manageable for would-be fitness buffs by cramming truly intense efforts into as little as 25 minutes.

Kyle Sevits, Garrett ...

Focus on space debris: Envisat

2012-10-12

Space debris came into focus last week at the International Astronautical Congress in Naples, Italy. Envisat, ESA's largest Earth observation satellite, ended its mission last spring and was a subject of major interest in the Space Debris and Legal session.

Envisat was planned and designed in 1987, a time when space debris was not considered to be a serious problem and before the existence of mitigation guidelines, established by the UN in 2007 and adopted the next year by ESA for all of its projects.

Only later, during the post-launch operational phase, did Envisat's ...

Discovery reveals important clues to cancer metastasis

2012-10-12

BOSTON – In recent years investigators have discovered that breast tumors are influenced by more than just the cancer cells within them. A variety of noncancerous cells, which in many cases constitute the majority of the tumor mass, form what is known as the "tumor microenvironment." This sea of noncancerous cells and the products they deposit appear to play key roles in tumor pathogenesis.

Among the key accomplices in the tumor microenvironment are mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), a group of adult progenitor cells which have been shown to help breast cancers maneuver and ...

Nerve and muscle activity vary across menstrual cycle

2012-10-12

WESTMINSTER, CO (October 10, 2012)—Numerous studies have shown that female athletes are more likely to get knee injuries, especially anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears and chronic pain, than their male counterparts. While previous research has focused on biomechanical differences as the main source of these problems, a new study suggests another distinction that could play a role: changes across the menstrual cycle in nerves that control muscle activity. The finding may eventually lead to new ways to prevent knee problems in female athletes.

Matthew Tenan, Yi-Ling ...

UT study: Natural playgrounds more beneficial to children, inspire more play

2012-10-12

KNOXVILLE—Children who play on playgrounds that incorporate natural elements like logs and flowers tend to be more active than those who play on traditional playgrounds with metal and brightly colored equipment, according to a recent study from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

They also appear to use their imagination more, according to the report.

The study, which examined changes in physical activity levels and patterns in young children exposed to both traditional and natural playgrounds, is among the first of its kind in the United States, according to Dawn ...