(Press-News.org) MADISON — Scientists have identified three neighboring genes that make soybeans resistant to the most damaging disease of soybean. The genes exist side-by-side on a stretch of chromosome, but only give resistance when that stretch is duplicated several times in the plant.

"Soybean cyst nematode is the most important disease of soybean, according to yield loss, worldwide, year after year," says senior author Andrew Bent, professor of plant pathology at University of Wisconsin-Madison. "As we try to feed a world that is going from 6 billion toward 9 billion people, soybean is one of the most important sources of protein and food oil."

The nematode is a tough opponent, able to live for years in the soil, and chemicals that kill it are highly toxic and persistent, Bent says. Planting soybeans bred to contain a genetic structure called Rhg1 is the preferred defense against the cyst nematode, currently in use on millions of soybean acres worldwide.

Until now, scientists knew few details about how Rhg1 works. In a study published today in the journal Science, Bent, graduate student David Cook, and collaborators including Matthew Hudson of the University of Illinois, showed that Rhg1 actually houses three genes that work together to confer nematode resistance. Although a single copy of Rhg1 does not make the plant resistant, plants with 10 copies of this three-gene structure do grow well in a field infected with the nematode.

The new finding is noteworthy for several reasons beyond the fact that Rhg1 limits a disease that still causes over $1 billion in U.S. soybean yield losses every year, says Bent. "Having several genes right next to each other that all control the same trait is really common in microbes and fungi, but it's very uncommon in multicellular higher organisms."

Second, although the phenomenon of "multiple copy numbers" — repeats of a stretch of DNA — has been seen before, "this is a demonstration that the multiple copies are what make the genes practically effective."

Third, the multiple copies concern a three-gene sequence rather than an individual gene. "We have known that genes get duplicated, but it's very unusual to have a small block of genes duplicated so many times," Bent says. "This is an odd structure."

Many details remain to be worked out, including exactly how the three genes fight the nematode. Because two of the genes are involved with transporting chemicals inside and between cells, "an obvious theory is that the plant is transporting something differently," Bent says, "but we don't know if this is a compound that is toxic to the nematode or something the nematode needs. We can't assume that the plant is poisoning the nematode. It may not be cooperating with a parasite that relies on plant chemicals for survival."

Apparently, it's the sheer number of the triple-genes that makes soybeans resistant, Bent says. "We have evidence that what confers the resistance is higher expression of all three genes," not a mutation in the genes. "The fact that the genes are making more of their product is what makes for resistance."

Identifying the genes needed for resistance should help plant breeders quickly identify resistant plants, speeding the quest to breed soybeans with stronger nematode resistance.

Biotechnologists can also now work with these genes to achieve better nematode resistance.

More broadly, Bent notes that multiple gene copies are being found more commonly, so finding repeats of a string of genes with a single function "may not be a one-shot thing. Is this the tip of the iceberg? Is there a lot more of this going on than we know?"

As gene sequencing gets cheaper and faster, "people are discovering that these copy number variations are much more common than we suspected, especially in plants," Bent says. "Now, we have given a concrete example of a useful trait, that is explainable due to the copy number variation of a string containing several active genes."

INFORMATION:

— David J. Tenenbaum, 608-265-8549, djtenenb@wisc.edu

END

Sophia Antipolis, 12 October 2012: Urgent actions including smoking bans in public places, salt restrictions and improved blood pressure control are needed to fight rising cardiovascular disease in China. Half of male physicians in China smoke and they can lead the way to healthy lifestyles by kicking the habit.

Cardiovascular disease is the top cause of death in China and causes more than 40% of all deaths.

"Every year three million Chinese people die from cardiovascular disease and every 10 seconds there is one death from CVD in China," said Professor Dayi Hu, chief ...

The relatively new field in microbiology that focuses on quorum sensing has been making strides in understanding how bacteria communicate and cooperate. Quorum sensing describes the bacterial communication between cells that allows them to recognize and react to the size of their surrounding cell population. While a cell's output of extracellular products, or "public goods," is dependent on the size of its surrounding population, scientists have discovered that quorum sensing, a type of bacterial communication, controls when cells release these public goods into their environments. ...

Scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego have used 20 years of satellite data to reveal a geological oddity unlike any seen on Earth.

At the border of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile sits the Altiplano-Puna plateau in the central Andes region, home to the largest active magma body in Earth's continental crust and known for a long history of massive volcanic eruptions. A study led by Yuri Fialko of Scripps and Jill Pearse of the Alberta Geological Survey has revealed that magma is forming a big blob in the middle of the crust, pushing up the earth's ...

October 12, 2012 – The human mouth is home to a teeming community of microbes, yet still relatively little is known about what determines the specific types of microorganisms that live there. Is it your genes that decide who lives in the microbial village, or is it your environment? In a study published online in Genome Research (www.genome.org), researchers have shown that environment plays a much larger role in determining oral microbiota than expected, a finding that sheds new light on a major factor in oral health.

Our oral microbiome begins to take shape as soon ...

(Edmonton) A meteorite that landed in the Moroccan desert 14 months ago is providing more information about Mars, the planet where it originated.

University of Alberta researcher Chris Herd helped in the study of the Tissint meteorite, in which traces of Mars' unique atmosphere are trapped.

"Our team matched traces of gases found inside the Tissint meteorite with samples of Mars' atmosphere collected in 1976 by Viking, NASA's Mars lander mission," said Herd.

Herd explained that 600 million years ago the meteorite started out as a fairly typical volcanic rock on the surface ...

Fly eyes have the fastest visual responses in the animal kingdom, but how they achieve this has long been an enigma. A new study shows that their rapid vision may be a result of their photoreceptors - specialised cells found in the retina - physically contracting in response to light. The mechanical force then generates electrical responses that are sent to the brain much faster than, for example, in our own eyes, where responses are generated using traditional chemical messengers. The study was published today, 12 October, in the journal Science.

It had been thought ...

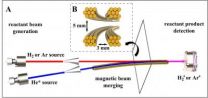

At very low temperatures, close to absolute zero, chemical reactions may proceed at a much higher rate than classical chemistry says they should – because in this extreme chill, quantum effects enter the picture. A Weizmann Institute team has now confirmed this experimentally; their results would not only provide insight into processes in the intriguing quantum world in which particles act as waves, it might explain how chemical reactions occur in the vast frigid regions of interstellar space.

Long-standing predictions are that quantum effects should allow the formation ...

VALHALLA, October 11, 2012—A New York Medical College developmental biologist whose life's work has supported the theory of evolution has developed a concept that dramatically alters one of its basic assumptions—that survival is based on a change's functional advantage if it is to persist. Stuart A. Newman, Ph.D., professor of cell biology and anatomy, offers an alternative model in proposing that the origination of the structural motifs of animal form were actually predictable and relatively sudden, with abrupt morphological transformations favored during the early period ...

TORONTO, ON – Psychologists at the University of Toronto and the Georgia Institute of Technology – commonly known as Georgia Tech – have shown that an individual's inability to recognize once-familiar faces and objects may have as much to do with difficulty perceiving their distinct features as it does with the capacity to recall from memory.

A study published in the October issue of Hippocampus suggests that memory impairments for people diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer's disease may in part be due to problems with determining the differences between similar objects. ...

WESTMINSTER, CO (October 10, 2012)—One of life's certainties is that everyone ages. However, it's also certain that not everyone ages at the same rate. According to recent research being presented this week, the cardiovascular system of people with type 2 diabetes shows signs of aging significantly earlier than those without the disease. However, exercise can help to slow down this premature aging, bringing the aging of type 2 diabetes patients' cardiovascular systems closer to that of people without the disease, says researcher Amy Huebschmann of the University of Colorado ...