(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA – October 25, 2012 – Explosive advancement in human genome sequencing opens new possibilities for identifying the genetic roots of certain diseases and finding cures. However, so many variations among individual genomes exist that identifying mutations responsible for a specific disease has in many cases proven an insurmountable challenge. But now a new study by scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI), Scripps Health, and Scripps Translational Science Institute (STSI) reveals that by comparing the genomes of diseased patients with the genomes of people with sufficiently similar ancestries could dramatically simplify searches for harmful mutations, opening new treatment possibilities.

The work, reported recently in the journal Frontiers in Genetics: Applied Genetic Epidemiology, should speed the search for the causes of many diseases and provide critical guidance to the genomics field for maximizing the potential benefits of growing genome databases.

Much work is already under way to sequence the DNA of people suffering from diseases with unknown causes, called idiopathic conditions, to find the roots of their problems. Unlike more complex conditions such as diabetes, in some cases a limited number of genetic defects, or even a single mutation, can cause an idiopathic disease. Identifying those critical mutations can lead to effective treatments for previously mysterious problems.

Complicated Searches

While there have been some successes, in many other instances the genetic basis of an idiopathic disease remains elusive. Among other groups, The National Human Genome Research Institute runs searches for idiopathic disease sufferers and is able to find offending gene sequences only about 30 percent of the time. "One explanation for that other 70 percent might be that the diseases are enormously complex," said the new study's senior author Nicholas Schork, a professor at TSRI, director of research for Scripps Health's genomic medicine program, and director of biostatistics and bioinformatics at STSI, "but it could be that they're still searching in the noise."

The new work offers a likely filter for much of that noise. The results show that comparing a person's DNA sequence against existing genomes for those whose ancestry is not sufficiently similar, as is typically the case, can cause serious problems. Countless differences that seem unique to a patient might instead be DNA variants carried by everyone with the same ancestry. A researcher might, for instance, identify hundreds of variants and not be able to zero in on the one responsible for a disease.

But the new results show that comparing closer ancestry matches will dramatically reduce the number of variants identified as potentially responsible for a disease, reducing a search to a workable number.

For the work, the team developed a tool called the Scripps Genome Adviser. This processing framework uses a supercomputer to incorporate a variety of databases and algorithms to identify DNA variants in a particular genome relative to reference genomes. It then uses algorithms to analyze these variants and predict whether they have any physiological effects, and if so what those might be.

The team began with nearly 60 whole human genome databases and ran three key types of computing experiments. First the researchers identified the number of variants in the reference human genomes and found that on average each has millions of variants, about 12,000 of which have functional effects. Then the scientists looked at the rates at which variants appeared in various ancestry lines.

Honoring Ancestry

Importantly, the scientists didn't stop there. They deliberately inserted a mutation known to cause disease into a genome, then ran this genome through the Adviser to see how effectively it could identify that known variant as unique.

When the team ran the searches comparing that altered genome against a reference panel of genomes that included different ancestries, the known variant remained effectively lost in a sea of other variants. But comparison against genomes of similar ancestry dramatically reduced the number of variants identified, allowing identification of the inserted disease-causing gene.

A study published simultaneously with the Scripps team's paper by Professor Carlos Bustamante and colleagues from Stanford University also pointed to ancestry's importance, but this is the first time a team has been able to look at the problem on the whole-genome scale. "Others have indeed recognized ancestry as important," said Schork, "but no one had shown how much it could haunt a particular study, especially on a whole genome basis."

As importantly, prior to this study it wasn't clear how to address the ancestry issue. But the new study provides clear direction. The team calculated that identification of the vast majority of ancestral variants can be performed successfully with a reference panel of less than 20 genomes—though it could well take more to identify a particular ancestry group's rarest deviations. Of course, most people have more than one ancestry line, meaning that in practice a patient's reference panel would need to include multiple reference groups.

This result should act as a guide for continuing genomics work. Many ancestries are already well represented, meaning that assembling an effective reference panel is possible in some cases. But the number of whole genomes from a particular ancestral group isn't the only consideration. Ideally, reference genomes need to be from relatively disease-free people, meaning subjects who lived to an old age without major complications from genetic conditions.

Recognizing the importance of ancestral comparisons, researchers and companies can now deliberately work to fill any holes. "Building those sorts of resources could only benefit the community," said Schork. In fact, Schork, Ali Torkamani and others at Scripps are collaborating with Complete Genomics, Inc., a whole genome sequencing company in Mountain View, CA, to develop appropriate reference panels for clinicians and researchers.

Deciphering Diseases

Schork and his colleagues are already working toward broader application of their results using an increasingly advanced version of the tool. While processing a single person's genome to identify and analyze variants took about four days when the project began, today the Adviser can accomplish the task in about 30 minutes.

Along with the paper's lead author Torkamani, Schork is a founder of a company called Cypher Genomics that has licensed the Scripps Genome Adviser for disease-focused research. The teams in both industry and academia hope not only to continue idiopathic disease research, but also to apply similar principles to search for the causes of more complex congenital conditions. "The broader message of our work is that you have to take ancestry into account no matter what disease you're studying," said Schork.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Torkamani and Schork, other authors on the paper, "Clinical Implications of Human Population Differences in Genome-wide Rates of Functional Genotypes," are Phillip Pham, Ondrej Libiger, Vikas Bansal, Guangfa Zhang, Ashley Scott-Van Zeeland, Ryan Tewhey and Eric Topol (director of STSI). For more information on the paper (doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00211), see http://www.frontiersin.org/Applied_Genetic_Epidemiology/10.3389/fgene.2012.00211/abstract

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers 5 UL1 RR025774, 5 U01 DA024417, 5 R01 HL089655, 5 R01 DA030976, 5 R01 AG035020, 1 R01 MH093500, 2 U19 AI063603, 2 U19 AG023122, 5 P01 AG027734, 1 U01 HG006476-01), the Stand Up to Cancer Foundation, the Price Foundation and Scripps Genomic Medicine.

New genomics study shows ancestry could help solve disease riddles

2012-10-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A 'nanoscale landscape' controls flow of surface electrons on a topological insulator

2012-10-26

CHESTNUT HILL, MA (October 25, 2012) – In the relatively new scientific frontier of topological insulators, theoretical and experimental physicists have been studying the surfaces of these unique materials for insights into the behavior of electrons that display some very un-electron-like properties.

In topological insulators, electrons can behave more like photons, or particles of light. The hitch is that unlike photons, electrons have a mass that normally plays a defining role in their behavior. In the world of quantum physics, where everyday materials take on surprising ...

Changing the balance of bacteria in drinking water to benefit consumers

2012-10-26

WASHINGTON, Oct. 25, 2012 — The latest episode in the American Chemical Society's (ACS') award-winning Global Challenges/Chemistry Solutions podcast series reports that scientists have discovered a plausible way to manipulate the populations of mostly beneficial microbes in "purified" drinking water to potentially benefit consumers.

Based on a report by Lutgarde Raskin, Ph.D., in ACS' journal Environmental Science & Technology, the new podcast is available without charge at iTunes and from www.acs.org/globalchallenges.

In the new episode, Raskin explains that municipal ...

Small marine organisms' big changes could affect world climate

2012-10-26

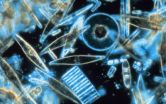

In the future, warmer waters could significantly change ocean distribution of populations of phytoplankton, tiny organisms that could have a major effect on climate change.

Reporting in this week's online journal Science Express, researchers show that by the end of the 21st century, warmer oceans will cause populations of these marine microorganisms to thrive near the poles and shrink in equatorial waters.

"In the tropical oceans, we are predicting a 40 percent drop in potential diversity, the number of strains of phytoplankton," says Mridul Thomas, a biologist at Michigan ...

Small organisms could dramatically impact world's climate

2012-10-26

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Warmer oceans in the future could significantly alter populations of phytoplankton, tiny organisms that could have a major impact on climate change.

In the current issue of Science Express, Michigan State University researchers show that by the end of the 21st century, warmer oceans will cause populations of these marine microorganisms to thrive near the poles and may shrink in equatorial waters. Since phytoplankton play a key role in the food chain and the world's cycles of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous and other elements, a drastic drop could have ...

Individual gene differences can be tested in zebrafish

2012-10-26

HERSHEY, Pa. -- The zebrafish is a potential tool for testing one class of unique individual genetic differences found in humans, and may yield information helpful for the emerging field of personalized medicine, according to a team led by Penn State College of Medicine scientists. The differences, or mutations, in question create minor changes in amino acids -- the building blocks of DNA -- from person to person. Zebrafish can be used as a model to understand what biological effects result from these genetic mutations.

Personalized medicine uses modern technology and ...

Monster galaxy may have been stirred up by black-hole mischief

2012-10-26

Astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have obtained a remarkable new view of a whopper of an elliptical galaxy, with a core bigger than any seen before. There are two intriguing explanations for the puffed up core, both related to the action of one or more black holes, and the researchers have not yet been able to determine which is correct.

Spanning a little over one million light-years, the galaxy is about ten times the diameter of the Milky Way galaxy. The bloated galaxy is a member of an unusual class of galaxies with an unusually diffuse core filled ...

Exercise boosts satisfaction with life, researchers find

2012-10-26

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Had a bad day? Extending your normal exercise routine by a few minutes may be the solution, according to Penn State researchers, who found that people's satisfaction with life was higher on days when they exercised more than usual.

"We found that people's satisfaction with life was directly impacted by their daily physical activity," said Jaclyn Maher, graduate student in kinesiology. "The findings reinforce the idea that physical activity is a health behavior with important consequences for daily well-being and should be considered when developing ...

Robots in the home: Will older adults roll out the welcome mat?

2012-10-26

Robots have the potential to help older adults with daily activities that can become more challenging with age. But are people willing to use and accept the new technology? A study by the Georgia Institute of Technology indicates the answer is yes, unless the tasks involve personal care or social activities.

After showing adults (ages 65 to 93 years) a video of a robot's capabilities, researchers interviewed them about their willingness for assistance with 48 common household tasks. Participants generally preferred robotic help over human help for chores such as cleaning ...

New genes discovered for adult BMI levels

2012-10-26

A large international study has identified three new gene variants associated with body mass index (BMI) levels in adults. The scientific consortium, numbering approximately 200 researchers, performed a meta-analysis of 46 studies, covering gene data from nearly 109,000 adults, spanning four ethnic groups.

In discovering intriguing links to lipid-related diseases, type 2 diabetes and other disorders, the IBC 50K SNP Array BMI Consortium's study may provide fundamental insights into the biology of adult obesity. Scientists from the Center for Applied Genomics at The Children's ...

Academia should fulfill social contract by supporting bioscience startups, case study says

2012-10-26

Universities not only provide the ideal petri dish for cultivating bioscience with commercial potential, but have a moral obligation to do so, given the opportunity to translate public funding into health and jobs, according to a new case study by UCSF researchers.

In an analysis published Oct. 24, 2012 in Science Translational Medicine, researchers at the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3) assessed the impact of the institute's efforts over the past eight years in supporting entrepreneurs on the three UC campuses in which it operates: UCSF, UC Berkeley ...