(Press-News.org) Physicists have proposed an experiment that could force us to make a choice between extremes to describe the behaviour of the Universe.

The proposal comes from an international team of researchers from Switzerland, Belgium, Spain and Singapore, and is published today in Nature Physics. It is based on what the researchers call a 'hidden influence inequality'. This exposes how quantum predictions challenge our best understanding about the nature of space and time, Einstein's theory of relativity.

"We are interested in whether we can explain the funky phenomena we observe without sacrificing our sense of things happening smoothly in space and time," says Jean-Daniel Bancal, one of the researchers behind the new result, who carried out the research at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. He is now at the Centre for Quantum Technologies at the National University of Singapore.

Excitingly, there is a real prospect of performing this test.

The implications of quantum theory have been troubling physicists since the theory was invented in the early 20th Century. The problem is that quantum theory predicts bizarre behaviour for particles – such as two 'entangled' particles behaving as one even when far apart. This seems to violate our sense of cause and effect in space and time. Physicists call such behaviour 'nonlocal'.

It was Einstein who first drew attention to the worrying implications of what he termed the "spooky action at a distance" predicted by quantum mechanics. Measure one in a pair of entangled atoms to have its magnetic 'spin' pointing up, for example, and quantum physics says the other can immediately be found pointing in the opposite direction, wherever it is and even when one could not predict beforehand which particle would do what. Common sense tells us that any such coordinated behaviour must result from one of two arrangements. First, it could be arranged in advance. The second option is that it could be synchronised by some signal sent between the particles.

In the 1960s, John Bell came up with the first test to see whether entangled particles followed common sense. Specifically, a test of a 'Bell inequality' checks whether two particles' behaviour could have been based on prior arrangements. If measurements violate the inequality, pairs of particles are doing what quantum theory says: acting without any 'local hidden variables' directing their fate. Starting in the 1980s, experiments have found violations of Bell inequalities time and time again.

Quantum theory was the winner, it seemed. However, conventional tests of Bell inequalities can never completely kill hope of a common sense story involving signals that don't flout the principles of relativity. That's why the researchers set out to devise a new inequality that would probe the role of signals directly.

Experiments have already shown that if you want to invoke signals to explain things, the signals would have to be travelling faster than light – more than 10,000 times the speed of light, in fact. To those who know that Einstein's relativity sets the speed of light as a universal speed limit, the idea of signals travelling 10,000 times as fast as light already sets alarm bells ringing. However, physicists have a getout: such signals might stay as 'hidden influences' – useable for nothing, and thus not violating relativity. Only if the signals can be harnessed for faster-than-light communication do they openly contradict relativity.

The new hidden influence inequality shows that the getout won't work when it comes to quantum predictions. To derive their inequality, which sets up a measurement of entanglement between four particles, the researchers considered what behaviours are possible for four particles that are connected by influences that stay hidden and that travel at some arbitrary finite speed.

Mathematically (and mind-bogglingly), these constraints define an 80-dimensional object. The testable hidden influence inequality is the boundary of the shadow this 80-dimensional shape casts in 44 dimensions. The researchers showed that quantum predictions can lie outside this boundary, which means they are going against one of the assumptions. Outside the boundary, either the influences can't stay hidden, or they must have infinite speed.

Experimental groups can already entangle four particles, so a test is feasible in the near future (though the precision of experiments will need to improve to make the difference measurable). Such a test will boil down to measuring a single number. In a Universe following the standard relativistic laws we are used to, 7 is the limit. If nature behaves as quantum physics predicts, the result can go up to 7.3.

So if the result is greater than 7 – in other words, if the quantum nature of the world is confirmed – what will it mean?

Here, there are two choices. On the one hand, there is the option to defy relativity and 'unhide' the influences, which means accepting faster-than-light communication. Relativity is a successful theory that researchers would not call into question lightly, so for many physicists this is seen as the most extreme possibility.

The remaining option is to accept that influences must be infinitely fast – or that there exists some process that has an equivalent effect when viewed in our spacetime. The current test couldn't distinguish. Either way, it would mean that the Universe is fundamentally nonlocal, in the sense that every bit of the Universe can be connected to any other bit anywhere, instantly. That such connections are possible defies our everyday intuition and represents another extreme solution, but arguably preferable to faster-than-light communication.

"Our result gives weight to the idea that quantum correlations somehow arise from outside spacetime, in the sense that no story in space and time can describe them," says Nicolas Gisin, Professor at the University of Geneva, Switzerland, and member of the team.

INFORMATION:

The researchers that carried out the work, in addition to Dr Bancal and Prof Gisin, are Dr Stefano Pironio from the Free University of Bruxelles in Belgium, Professor Antonio Acín from the Institute of Photonic Sciences (ICFO) in Barcelona, Dr Yeong-Cherng Liang from the University of Geneva, and Professor Valerio Scarani from the Centre for Quantum Technologies and the Department of Physics of the National University of Singapore.

Reference: J.-D. Bancal et al, Quantum nonlocality based on finite-speed causal influences leads to superluminal signalling", Nature Physics, DOI:10.1038/NPHYS2460 (2012).

Researcher Contacts

Dr Jean-Daniel Bancal

Centre for Quantum Technologies, National University of Singapore

+65 65165626

cqtbjd@nus.edu.sg

Professor Nicolas Gisin

University of Geneva, Switzerland

+41 2 2379 0502 (office) / +41 79 7762317 (mobile)

Nicolas.Gisin@unige.ch

Professor Antonio Acin

ICFO-The Institute of Photonic Sciences, Spain

+34 93 553 40 62

Antonio.Acin@icfo.es

Researchers look beyond space and time to cope with quantum theory

2012-10-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NIH researchers identify novel genes that may drive rare, aggressive form of uterine cancer

2012-10-29

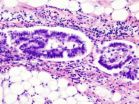

Researchers have identified several genes that are linked to one of the most lethal forms of uterine cancer, serous endometrial cancer. The researchers describe how three of the genes found in the study are frequently altered in the disease, suggesting that the genes drive the development of tumors. The findings appear in the Oct. 28, 2012, advance online issue of Nature Genetics. The team was led by researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health.

Cancer of the uterine lining, or endometrium, is the most ...

Key discovered to how chemotherapy drug causes heart failure

2012-10-29

HOUSTON - Doxorubicin, a 50-year-old chemotherapy drug still in widespread use against a variety of cancers, has long been known to destroy heart tissue, as well as tumors, in some patients.

Scientists have identified an unexpected mechanism via the enzyme Top2b that drives the drug's attack on heart muscle, providing a new approach for identifying patients who can safely tolerate doxorubicin and for developing new drugs. A team led by scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center reports its findings about the general DNA-damaging drug today in the ...

How to make stem cells – nuclear reprogramming moves a step forward

2012-10-29

The idea of taking a mature cell and removing its identity (nuclear reprogramming) so that it can then become any kind of cell, holds great promise for repairing damaged tissue or replacing bone marrow after chemotherapy. Hot on the heels of his recent Nobel prize Dr John B. Gurdon has published today in BioMed Central's open access journal Epigenetics & Chromatin research showing that histone H3.3 deposited by the histone-interacting protein HIRA is a key step in reverting nuclei to a pluripotent type, capable of being any one of many cell types.

All of an individual's ...

US shale gas drives up coal exports

2012-10-29

US CO2 emissions from domestic energy have declined by 8.6% since a peak in 2005, the equivalent of 1.4% per year.

However, the researchers warn that more than half of the recent emissions reductions in the power sector may be displaced overseas by the trade in coal.

Dr John Broderick, lead author on the report from the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, comments: "Research papers and newspaper column inches have focussed on the relative emissions from coal and gas.

"However, it is the total quantity of CO2 from the energy system that matters to the climate. ...

Atrial fibrillation is a 'modifiable' risk factor for stroke

2012-10-29

Atrial fibrillation, whose prevalence continues to rise, was described last year as the "new epidemic" in cardiovascular disease, even though AF can be successfully controlled by the detection and management of risk factors, by rhythm control treatments, and by the use of antithrombotic therapies.(1) These therapies have been improved in the past few years by the introduction of new anticoagulant drugs, such that AF - like high blood pressure or smoking - may now be considered a "modifiable" risk factor for stroke, whose treatment can reduce the degree of risk.

Professor ...

Uncertainty of future South Pacific Island rainfall explained

2012-10-29

With greenhouse warming, rainfall in the South Pacific islands will depend on two competing effects – an increase due to overall warming and a decrease due to changes in atmospheric water transport – according to a study by an international team of scientists around Matthew Widlansky and Axel Timmermann at the International Pacific Research Center, University of Hawaii at Manoa. In the South Pacific, the study shows, these two effects sometimes cancel each other out, resulting in highly uncertain rainfall projections. Results of the study are published in the 28 October ...

Primates' brains make visual maps using triangular grids

2012-10-29

Primates' brains see the world through triangular grids, according to a new study published online Sunday in the journal Nature.

Scientists at Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, have identified grid cells, neurons that fire in repeating triangular patterns as the eyes explore visual scenes, in the brains of rhesus monkeys.

The finding has implications for understanding how humans form and remember mental maps of the world, as well as how neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's erode those abilities. This is the first time grid cells have ...

Mechanism found for destruction of key allergy-inducing complexes, Stanford researchers say

2012-10-29

STANFORD, Calif. — Researchers have learned how a man-made molecule destroys complexes that induce allergic responses — a discovery that could lead to the development of highly potent, rapidly acting interventions for a host of acute allergic reactions.

The study, which will be published online Oct. 28 in Nature, was led by scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine and the University of Bern, Switzerland.

The new inhibitor disarms IgE antibodies, pivotal players in acute allergies, by detaching the antibody from its partner in crime, a molecule called ...

Yeast model offers clues to possible drug targets for Lou Gehrig's disease, study shows

2012-10-29

STANFORD, Calif. — Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also called Lou Gehrig's disease, is a devastatingly cruel neurodegenerative disorder that robs sufferers of the ability to move, speak and, finally, breathe. Now researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine and San Francisco's Gladstone Institutes have used baker's yeast — a tiny, one-celled organism — to identify a chink in the armor of the currently incurable disease that may eventually lead to new therapies for human patients.

"Even though yeast and humans are separated by a billion years of evolution, ...

Test developed to detect early-stage diseases with naked eye

2012-10-29

Scientists have developed a prototype ultra-sensitive sensor that would enable doctors to detect the early stages of diseases and viruses with the naked eye, according to research published today in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

The team, from Imperial College London, report that their visual sensor technology is ten times more sensitive than the current gold standard methods for measuring biomarkers. These indicate the onset of diseases such as prostate cancer and infection by viruses including HIV.

The researchers say their sensor would benefit countries where ...