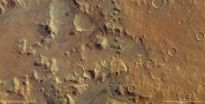

(Press-News.org) On 6 June, the high-resolution stereo camera on ESA's Mars Express revisited the Argyre basin as featured in our October release, but this time aiming at Nereidum Montes, some 380 km northeast of Hooke crater.

The stunning rugged terrain of Nereidum Montes marks the far northern extent of Argyre, one of the largest impact basins on Mars.

Nereidum Montes stretches almost 1150 km and was named by the noted Greek astronomer Eugène Michel Antoniadi (1870).

Based on his extensive observations of Mars, Antoniadi famously concluded that the 'canals' on Mars reported by Percival Lowell were, in fact, just an optical illusion.

The images captured by Mars Express show a portion of the region, displaying multiple fluvial, glacial and wind-driven features.

Extensive dendritic drainage patterns, seen towards the north (lower right side) of the first and topographic images, were formed when liquid water drained into deeper regions within the area.

On Earth, tree-like channels of this kind are usually formed by surface runoff after significant rainfall, or when snow or ice melts. Similar processes are thought to have occurred on Mars in the distant past, when scientists now know there to have been water on the surface of the Red Planet.

Several of the craters within the region, particularly in eastern parts (lower section) of the first image, show concentric crater fill, a distinctive martian process marked by rings of surface fluctuations within a crater rim.

The ratios between the diameter and depth of the filled craters suggest that there may still be water ice, possibly in the form of ancient glaciers, present below the dry surface debris cover.

Scientists have estimated that the water-ice depth in these craters varies from several tens up to hundreds of metres.

The largest crater on the south western side (top-left half) of the first and topographic images appears to have spilled out a glacier-like formation towards lower-lying parts of the region (shown as blue in the topographic image).

A smooth area to the east of (below) the glacial feature appears to be the youngest within the image, evidenced by an almost complete lack of cratering.

Another indication of subsurface water is seen in the fluidised ejecta blanket surrounding the crater at the northern edge (right-hand side) of the first and topographic images.

These ejecta structures can develop when a comet or asteroid hits a surface saturated with water or water ice.

Finally, throughout the images and often near the wind-sheltered sides of mounds and canyons, extensive rippling sand dune fields are seen to have formed.

In-depth studies of regions such as Nereidum Montes play an essential role in unlocking the geological past of our terrestrial neighbour, as well as helping to find exciting regions for future robotic and human explorers to visit.

INFORMATION:

Nereidum Montes helps unlock Mars' glacial past

2012-11-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

African American women with HIV/HCV less likely to die from liver disease

2012-11-01

A new study shows that African American women coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are less likely to die from liver disease than Caucasian or Hispanic women. Findings in the November issue of Hepatology, a journal published by Wiley on behalf of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, indicate that lower liver-related mortality in African American women was independent of other causes of death.

Medical evidence reports that nearly five million Americans are infected with HCV, with 80% having active virus in ...

Scientists create 'endless supply' of myelin-forming cells

2012-11-01

In a new study appearing this month in the Journal of Neuroscience, researchers have unlocked the complex cellular mechanics that instruct specific brain cells to continue to divide. This discovery overcomes a significant technical hurdle to potential human stem cell therapies; ensuring that an abundant supply of cells is available to study and ultimately treat people with diseases.

"One of the major factors that will determine the viability of stem cell therapies is access to a safe and reliable supply of cells," said University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) ...

Computational medicine enhances way doctors detect, treat disease

2012-11-01

Computational medicine, a fast-growing method of using computer models and sophisticated software to figure out how disease develops -- and how to thwart it -- has begun to leap off the drawing board and land in the hands of doctors who treat patients for heart ailments, cancer and other illnesses. Using digital tools, researchers have begun to use experimental and clinical data to build models that can unravel complex medical mysteries.

These are some of the conclusions of a new review of the field published in the Oct. 31 issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine. ...

New technique enables high-sensitivity view of cellular functions

2012-11-01

Troy, N.Y. – Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have developed an ultrasensitive method for detecting sugar molecules – or glycans – coming from living organisms, a breakthrough that will make possible a more detailed understanding of cellular functions than either genetic or proteomic (the study of proteins) information can provide. The researchers hope the new technique will revolutionize the study of glycans, which has been hampered by an inability to easily detect and identify minute quantities of these molecules.

"The glycome is richer in information ...

Novel technique to produce stem cells from peripheral blood

2012-11-01

Stem cells are a valuable resource for medical and biological research, but are difficult to study due to ethical and societal barriers. However, genetically manipulated cells from adults may provide a path to study stem cells that avoid any ethical concerns. A new video-protocol in JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments), details steps to generate human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) from cells in the peripheral blood. The technique has been developed by Boston University's Dr. Gustavo Mostoslavsky and his colleagues.

Stem cells are unique because they can ...

MIT and Northwestern economists find kinship networks play key role to access credit

2012-11-01

(Nov. 1, 2012 – Chicago, IL) In times of financial hardship, or when opportunities arise, the ability to borrow can be critical. Some people rely on commercial lenders, while others depend on relatives, especially in developing countries. But a new study shows that the presence of banks and relatives together are better than any one source individually.

The research, funded by the Consortium on Financial Services and Poverty (CFSP), suggests that not every household in a village needs to use the banking system directly in order to benefit in terms of buffering consumption, ...

Caffeine's effect on the brain's adenosine receptors visualized for the first time

2012-11-01

Reston, Va. (November 1, 2012) – Molecular imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) has enabled scientists for the first time to visualize binding sites of caffeine in the living human brain to explore possible positive and negative effects of caffeine consumption. According to research published in the November issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine, PET imaging with F-18-8-cyclopentyl-3-(3-fluoropropyl)-1-propylxanthine (F-18-CPFPX) shows that repeated intake of caffeinated beverages throughout a day results in up to 50 percent occupancy of the brain's A1 adenosine ...

USDA patents method to reduce ammonia emissions

2012-11-01

Capturing and recycling ammonia from livestock waste is possible using a process developed by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) researchers. This invention could help streamline on-farm nitrogen management by allowing farmers to reduce potentially harmful ammonia emissions and concentrate nitrogen in a liquid product to sell as fertilizer.

The work was conducted by Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientists Matias Vanotti and Ariel Szogi at the agency's Coastal Plains Soil, Water and Plant Research Center in Florence, S.C. ARS is USDA's chief intramural scientific ...

Solving a biological mystery

2012-11-01

Harvard scientists have solved the long-standing mystery of how some insects form the germ cells – the cellular precursors to the eggs and sperm necessary for sexual reproduction – and the answer is shedding new light on the evolutionary origins of a gene that had long been thought to be critical to the process.

As described in a November 1 paper published in Current Biology, a team of researchers led by Associate Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Cassandra Extavour discovered that a cricket, a so-called "lower" insect, possess a variation of a gene, called ...

Living donors fare well following liver transplantation

2012-11-01

Researchers in Japan report that health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for donors following living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) was better than the general Japanese population (the norm). This study—one of the largest to date—found that donors who developed two or more medical problems (co-morbidities) after donation had significantly decreased long-term HRQOL. Full findings are published in the November issue of Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

The shortage of viable donor organs continues to ...