(Press-News.org) Cambridge, Mass. – November 13, 2012 – Bioengineers at Harvard have developed a gel-based sponge that can be molded to any shape, loaded with drugs or stem cells, compressed to a fraction of its size, and delivered via injection. Once inside the body, it pops back to its original shape and gradually releases its cargo, before safely degrading.

The biocompatible technology, revealed this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, amounts to a prefabricated healing kit for a range of minimally invasive therapeutic applications, including regenerative medicine.

"What we've created is a three-dimensional structure that you could use to influence the cells in the tissue surrounding it and perhaps promote tissue formation," explains principal investigator David J. Mooney, Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and a Core Faculty Member at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard.

"The simplest application is when you want bulking," Mooney explains. "If you want to introduce some material into the body to replace tissue that's been lost or that is deficient, this would be ideal. In other situations, you could use it to transplant stem cells if you're trying to promote tissue regeneration, or you might want to transplant immune cells, if you're looking at immunotherapy."

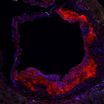

Consisting primarily of alginate, a seaweed-based jelly, the injectable sponge contains networks of large pores, which allow liquids and large molecules to easily flow through it. Mooney and his research team demonstrated that live cells can be attached to the walls of this network and delivered intact along with the sponge, through a small-bore needle. Mooney's team also demonstrated that the sponge can hold large and small proteins and drugs within the alginate jelly itself, which are gradually released as the biocompatible matrix starts to break down inside the body.

Normally, a scaffold like this would have to be implanted surgically. Gels can also be injected, but until now those gels would not have carried any inherent structure; they would simply flow to fill whatever space was available.

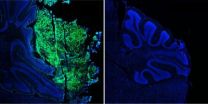

"Our scaffolds can be designed in any size and shape, and injected in situ as a safe, preformed, fully characterized, sterile, and controlled delivery device for cells and drugs," says lead author Sidi Bencherif, a postdoctoral research associate in Mooney's lab at SEAS and at the Wyss Institute.

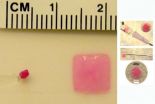

Bencherif and his colleagues pushed pink squares, hearts, and stars through a syringe to demonstrate the versatility and robustness of their gel.

The spongelike gel is formed through a freezing process called cryogelation. As the water in the alginate solution starts to freeze, pure ice crystals form, which makes the surrounding gel more concentrated as it sets. Later on, the ice crystals melt, leaving behind a network of pores. By carefully calibrating this mixture and the timing of the freezing process, Mooney, Bencherif, and their colleagues found that they could produce a gel that is extremely strong and compressible, unlike most alginate gels, which are brittle.

The resulting "cryogel" fills a gap that has previously been unmet in biomedical engineering.

"These injectable cryogels will be especially useful for a number of clinical applications including cell therapy, tissue engineering, dermal filler in cosmetics, drug delivery, and scaffold-based immunotherapy," says Bencherif. "Furthermore, the ability of these materials to reassume specific, pre-defined shapes after injection is likely to be useful in applications such as tissue patches where one desires a patch of a specific size and shape, and when one desires to fill a large defect site with multiple smaller objects. These could pack in such a manner to leave voids that enhance diffusional transport to and from the objects and the host, and promote vascularization around each object."

The next step in the team's research is to perfect the degradation rate of the scaffold so that it breaks down at the same rate at which newly grown tissue replaces it. Harvard's Office of Technology Development has filed patent applications on the invention and is actively pursuing licensing and commercialization opportunities.

INFORMATION:

Coauthors included R. Warren Sands, Deen Bhatta, and Catia S. Verbeke at SEAS; Praveen Arany at SEAS and the Wyss Institute; and David Edwards, who is Gordon McKay Professor of the Practice of Bioengineering at SEAS and a Core Faculty Member at the Wyss Institute.

The research was supported by the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, the National Institutes of Health, and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Injectable sponge delivers drugs, cells, and structure

Compressible bioscaffold pops back to its molded shape once inside the body

2012-11-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Targeting downstream proteins in cancer-causing pathway shows promise in cell, animal model

2012-11-14

PHILADELPHIA - The cancer-causing form of the gene Myc alters the metabolism of mitochondria, the cell's powerhouse, making it dependent on the amino acid glutamine for survival. In fact, 40 percent of all "hard-to-treat" cancers have a mutation in the Myc gene.

Accordingly, depriving cells of glutamine selectively induces programmed cell death in cells overexpressing mutant Myc.

Using Myc-active neuroblastoma cancer cells, a team led by Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator M. Celeste Simon, Ph.D., scientific director for the Abramson Family Cancer ...

Vitamin D may prevent clogged arteries in diabetics

2012-11-14

People with diabetes often develop clogged arteries that cause heart disease, and new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that low vitamin D levels are to blame.

In a study published Nov. 9 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, the researchers report that blood vessels are less like to clog in people with diabetes who get adequate vitamin D. But in patients with insufficient vitamin D, immune cells bind to blood vessels near the heart, then trap cholesterol to block those blood vessels.

"About 26 million Americans now have type ...

Being neurotic, and conscientious, a good combo for health

2012-11-14

Under certain circumstances neuroticism can be good for your health, according to a University of Rochester Medical Center study showing that some self-described neurotics also tended to have the lowest levels of Interleukin 6 (IL-6), a biomarker for inflammation and chronic disease.

Researchers made the preliminary discovery while conducting research into how psychosocial factors such as personality traits influence underlying biology, to predict harmful conditions like inflammation.

Known as one of the "Big 5" traits, neuroticism is usually marked by being moody, nervous, ...

Research strengthens link between obesity and dental health in homeless children

2012-11-14

Obesity and dental cavities increase and become epidemic as children living below the poverty level age, according to nurse researchers from the Case Western Reserve University and the University of Akron.

"It's the leading cause of chronic infections in children," said Marguerite DiMarco, associate professor at the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University.

Researchers Sheau-Huey Chiu, assistant professor, and graduate assistant Jessica L. Prokp, from the University of Akron's College of Nursing, contributed to the study.

Researchers ...

For brain tumors, origins matter

2012-11-14

Cancers arise when a normal cell acquires a mutation in a gene that regulates cellular growth or survival. But the particular cell this mutation happens in—the cell of origin—can have an enormous impact on the behavior of the tumor, and on the strategies used to treat it.

Robert Wechsler-Reya, Ph.D., professor and program director at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, and his team study medulloblastoma, the most common malignant brain cancer in children. A few years ago, they made an important discovery: medulloblastoma can originate from one of two cell types: ...

Stem cell finding could advance immunotherapy for lung cancer

2012-11-14

CINCINNATI—A University of Cincinnati (UC) Cancer Institute lung cancer research team reports that lung cancer stem cells can be isolated—and then grown—in a preclinical model, offering a new avenue for investigating immunotherapy treatment options that specifically target stem cells.

John C. Morris, MD, and his colleagues report their findings in the Nov. 13, 2012, issue of PLOS One, a peer-reviewed online publication that features original research from all disciplines within science and medicine.

Stem cells are unique cells that can divide and differentiate into ...

New type of bacterial protection found within cells

2012-11-14

Irvine, Calif., Nov. 13, 2012 — UC Irvine biologists have discovered that fats within cells store a class of proteins with potent antibacterial activity, revealing a previously unknown type of immune system response that targets and kills bacterial infections.

Steven Gross, UCI professor of developmental & cell biology, and colleagues identified this novel intercellular role of histone proteins in fruit flies, and it could herald a new approach to fighting bacterial growth within cells. The study appears today in eLife, a new peer-reviewed, open-access journal supported ...

Uranium exposure linked to increased lupus rate

2012-11-14

CINCINNATI—People living near a former uranium ore processing facility in Ohio are experiencing a higher than average rate of lupus, according a new study conducted by scientists at the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

Lupus is a chronic inflammatory disease that can affect the skin, joints, kidneys, lungs, nervous system and other organs of the body. The underlying causes of lupus are unknown, but it is usually more common in women of child-bearing age.

For this new study, a collaborative team of UC and Cincinnati Children's ...

Less of a shock

2012-11-14

Implantable defibrillators currently on the market apply between 600 and 900 volts to the heart, almost 10 times the voltage from an electric outlet, says Ajit H. Janardhan, MD, PhD, a cardiac electrophysiology fellow at the Washington University's School of Medicine.

After being shocked, he says, some patients get post-traumatic stress disorder. Patients may even go so far as to ask their physicians to remove the defibrillator, even though they understand that the device has saved their lives.

The huge shocks are not only unbearably painful, they damage the heart muscle ...

The road to language learning is iconic

2012-11-14

Languages are highly complex systems and yet most children seem to acquire language easily, even in the absence of formal instruction. New research on young children's use of British Sign Language (BSL) sheds light on one of the mechanisms - iconicity - that may endow children with this amazing ability.

For spoken and written language, the arbitrary relationship between a word's form – how it sounds or how it looks on paper – and its meaning is a particularly challenging feature of language acquisition. But one of the first things people notice about sign languages is ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

[Press-News.org] Injectable sponge delivers drugs, cells, and structureCompressible bioscaffold pops back to its molded shape once inside the body