(Press-News.org) TORONTO, ON – Astrophysicists at the University of Toronto and other institutions across the United States, Europe and Asia have discovered a 'super-Jupiter' around the massive star Kappa Andromedae. The object, which could represent the first new observed exoplanet system in almost four years, has a mass at least 13 times that of Jupiter and an orbit somewhat larger than Neptune's.

The host star around which the planet orbits has a mass 2.5 times that of the Sun, making it the highest mass star to ever host a directly observed planet. The star can be seen with the naked eye in the constellation Andromeda at a distance of about 170 light years.

"Our teamidentified a faint object located very close to Kappa Andromedae in January that looks much like other young, massive directly imaged planets but does not look like a star," said Thayne Currie, a post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics at the University of Toronto and coauthor of a paper titled "Direct imaging of a `super-Jupiter' around a massive star" to be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. "It's likely a directly imaged planet." The report on the study can be viewed on arXiv.org at http://arxiv.org/abs/1211.3744.

The researchers made the discovery based on an infrared imaging search carried out as part of the Strategic Explorations of Exoplanets and Disks with Subaru (SEEDS) program using the Subaru telescope located in Hawaii.

"Kappa Andromedae moves fast across the sky so it will appear to change position relative to more distant, background objects," Currie says. "When we reobserved it in July at multiple wavelengths, we saw the faint object again, located at about the same position as it was in January. This indicates that it is bound to the star and not an unrelated background object." Labelled by the researchers Kappa And b, it could be the first direct rendering of an exoplanet in two years and of a new exoplanet system in almost four years, ending a significant drought in the field.

In a single infrared snapshot, the tiny point of light that is Kappa And b is completely lost amid the overwhelming glare of the host star. The SEEDS observing team was able to distinguish the object's faint light using a technique known as angular differential imaging, which combines a time-series of individual images in a manner that allows for the otherwise overwhelming glare of the host star to be removed from the final, combined image.

Young planets retain significant heat from their formation, enhancing the brightness at infrared wavelengths. This makes young star systems attractive targets for direct imaging planet searches. However, despite this fact, the successful direct imaging of extrasolar planets is exceptionally rare, especially for orbital separations akin to our own solar system planets. The extraordinary differences in brightness between a star and a planet are a primary reason why only a handful of planets have ever been directly imaged around stars.

"Although astronomers have found over 750 planets around other stars, we actually directly detect light from the atmosphere of only a few of them," said Currie. "There are approximately six now. Kappa And b is one of them if our estimates for its age and mass are correct, which we think they are. The rest are only inferred directly."

The large mass of both the host star and gas giant provide a sharp contrast with our own solar system. Observers and theorists have argued recently that large stars like Kappa Andromedae are likely to have large planets, perhaps following a simple scaled-up model of our own solar system. But experts predict that there is a limit to such extrapolations; if a star is too massive, its powerful radiation may disrupt the normal planet formation process that would otherwise occur. The discovery of the super-Jupiter around Kappa Andromedae demonstrates that stars as large as 2.5 solar masses are still fully capable of producing planets within their primordial circumstellar disks.

"This planetary system is very different from our own," Currie says. "The star is much more massive than our Sun and Kappa And b is at least 10 times more massive than any planet in the solar system. And, Kappa And b is located further from the star than any of the solar system planets are from the Sun. Because it is generally much harder to form massive planets at large distances from the parent star, Kappa And b could really be a challenge for our theories about how planets form."

The SEEDS research team continues to study the Kappa And b emitted light across a broad wavelength range, in order to better understand the atmospheric chemistry of the gas giant, and constrain the orbital characteristics. The researchers also continue to explore the system for possible secondary planets, which may have influenced the Kappa And b formation and orbital evolution. These follow-up studies will yield further clues to the formation of the super-Jupiter, and planet formation in general around massive stars.

INFORMATION:

The observational data used for the discovery was obtained using the HiCIAO high-contrast imaging instrument and IRCS infrared camera at the Subaru telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawai'i, operated by National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ). The SEEDS survey is led by principal investigator Dr. Motohide Tamura (NAOJ). The lead author of the discovery paper is Dr. Joseph Carson of College of Charleston (CofC) and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany. The international research team includes scientists from NAOJ, CofC, MPIA, University of Amsterdam, Princeton University, Goddard Space Flight Center, and several other institutes. The investigation was made possible in part by support from the U.S. National Science Foundation.

MEDIA CONTACTS:

Thayne Currie

Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics

University of Toronto

currie@astro.utoronto.ca

416-978-6569

Sean Bettam

Communications, Faculty of Arts & Science

University of Toronto

s.bettam@utoronto.ca

416-946-7950

Astrophysicists identify a 'super-Jupiter' around a massive star

First directly observed exoplanet system in 4 years

2012-11-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

School exclusion policies contribute to educational failure, study shows

2012-11-19

AUSTIN, Texas — "Zero- tolerance" policies that rely heavily on suspensions and expulsions hinder teens who have been arrested from completing high school or pursuing a college degree, according to a new study from The University of Texas at Austin.

In Chicago, 25,000 male adolescents are arrested each year. One quarter of these arrests occurred in school, according to the Chicago Police Department. The stigma of a public arrest can haunt an individual for years — ultimately stunting academic achievement and transition into adulthood, says David Kirk, associate professor ...

Call to modernize antiquated climate negotiations

2012-11-19

The structure and processes of United Nations climate negotiations are "antiquated", unfair and obstruct attempts to reach agreements, according to research published today.

The findings come ahead of the 18th UN Climate Change Summit, which starts in Doha on November 26.

The study, led by Dr Heike Schroeder from the University of East Anglia (UEA) and the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, argues that the consensus-based decision making used by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) stifles progress and contributes to negotiating ...

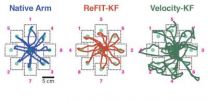

A better thought-controlled computer cursor

2012-11-19

When a paralyzed person imagines moving a limb, cells in the part of the brain that controls movement still activate as if trying to make the immobile limb work again. Despite neurological injury or disease that has severed the pathway between brain and muscle, the region where the signals originate remains intact and functional.

In recent years, neuroscientists and neuroengineers working in prosthetics have begun to develop brain-implantable sensors that can measure signals from individual neurons, and after passing those signals through a mathematical decode algorithm, ...

Fabrication on patterned silicon carbide produces bandgap to advance graphene electronics

2012-11-19

By fabricating graphene structures atop nanometer-scale "steps" etched into silicon carbide, researchers have for the first time created a substantial electronic bandgap in the material suitable for room-temperature electronics. Use of nanoscale topography to control the properties of graphene could facilitate fabrication of transistors and other devices, potentially opening the door for developing all-carbon integrated circuits.

Researchers have measured a bandgap of approximately 0.5 electron-volts in 1.4-nanometer bent sections of graphene nanoribbons. The development ...

Breakthrough nanoparticle halts multiple sclerosis

2012-11-19

New nanoparticle tricks and resets immune system in mice with MS

First MS approach that doesn't suppress immune system

Clinical trial for MS patients shows why nanoparticle is best option

Nanoparticle now being tested in Type 1 diabetes and asthma

CHICAGO --- In a breakthrough for nanotechnology and multiple sclerosis, a biodegradable nanoparticle turns out to be the perfect vehicle to stealthily deliver an antigen that tricks the immune system into stopping its attack on myelin and halt a model of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) in mice, according ...

Research breakthrough selectively represses the immune system

2012-11-19

Reporters, please see "For news media only" box at the end of the release for embargoed sound bites of researchers.

In a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS), researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have developed innovative technology to selectively inhibit the part of the immune system responsible for attacking myelin—the insulating material that encases nerve fibers and facilitates electrical communication between brain cells.

Autoimmune disorders occur when T-cells—a type of white blood cell within the immune system—mistake the body's own tissues ...

International team discovers likely basis of birth defect causing premature skull closure in infants

2012-11-19

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) -- An international team of geneticists, pediatricians, surgeons and epidemiologists from 23 institutions across three continents has identified two areas of the human genome associated with the most common form of non-syndromic craniosynostosis ― premature closure of the bony plates of the skull.

"We have discovered two genetic factors that are strongly associated with the most common form of premature closure of the skull," said Simeon Boyadjiev, professor of pediatrics and genetics, principal investigator for the study and leader of the International ...

Skin cells reveal DNA's genetic mosaic

2012-11-19

The prevailing wisdom has been that every cell in the body contains identical DNA. However, a new study of stem cells derived from the skin has found that genetic variations are widespread in the body's tissues, a finding with profound implications for genetic screening, according to Yale School of Medicine researchers.

Published in the Nov. 18 issue of Nature, the study paves the way for assessing the extent of gene variation, and for better understanding human development and disease.

"We found that humans are made up of a mosaic of cells with different genomes," ...

Optogenetics illuminates pathways of motivation through brain, Stanford study shows

2012-11-19

STANFORD, Calif. — Whether you are an apple tree or an antelope, survival depends on using your energy efficiently. In a difficult or dangerous situation, the key question is whether exerting effort — sending out roots in search of nutrients in a drought or running at top speed from a predator — will be worth the energy.

In a paper to be published online Nov. 18 in Nature, Karl Deisseroth, MD, PhD, a professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, and postdoctoral scholar Melissa Warden, PhD, describe how they have isolated ...

Stanford/Yale study gives insight into subtle genomic differences among our own cells

2012-11-19

STANFORD, Calif. — Stanford University School of Medicine scientists have demonstrated, in a study conducted jointly with researchers at Yale University, that induced-pluripotent stem cells — the embryonic-stem-cell lookalikes whose discovery a few years ago won this year's Nobel Prize in medicine — are not as genetically unstable as was thought.

The new study, which will be published online Nov. 18 in Nature, showed that what seemed to be changes in iPS cells' genetic makeup — presumed to be inflicted either in the course of their generation from adult cells or during ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

[Press-News.org] Astrophysicists identify a 'super-Jupiter' around a massive starFirst directly observed exoplanet system in 4 years