(Press-News.org) Chromosomes - long, linear DNA molecules – are capped at their ends with special DNA structures called telomeres and an assortment of proteins, which together act as a protective sheath. Telomeres are maintained through the interactions between an enzyme, telomerase, and several accessory proteins. Researchers at The Wistar Institute have defined the structure of one of these critical proteins in yeast.

Understanding how telomeres keep chromosomes – and by extension, genomes – intact is an area of intense scientific focus in the fields of both aging and cancer. In aging, the DNA of telomeres eventually erodes faster than telomerase and its accessory proteins can maintain it, and cells die. In cancer, tumor cells hijack the process, subverting the natural method by which our bodies limit cell growth; cancer cells, then, can grow and multiply unchecked.

One of these accessory proteins, Cdc13, is integral to telomere maintenance and essential for cell viability in yeast, according to researchers at The Wistar Institute. In a study published in the journal Structure, available online now, a team of scientists led by Emmanuel Skordalakes, Ph.D., an associate professor in The Wistar Institute Cancer Center's Gene Expression and Regulation Program, has determined how mutations in a particular region of Cdc13 can lead to defects in telomeres that could jeopardize DNA.

Cdc13 normally functions as a matched-set, where two copies of the protein form what is known as a dimer. Skordalakes found that mutations in a region of Cdc13 (called OB2) prevent Cdc13 copies from binding to each other. The findings help explain the biology of this key telomere maintenance protein, and may eventually lead to novel anticancer therapeutic if their findings translate to a similar molecular system used to maintain human telomeres, Skordalakes says.

"If we could target the OB2 region of Cdc13, for example, it would throw a wrench in the works of telomere maintenance," said Skordalakes. "If you can disrupt recruitment of telomerase in humans, you could potentially drive cells to death."

Cdc13 serves a dual function in telomere replication. First, it keeps the cells' natural DNA repair mechanisms from mistaking the telomere for a broken stretch of DNA, which could cause genetic mayhem if such repair proteins fuse the ends of two chromosomes together, for example. Secondly, Cdc13 recruits telomerase and related proteins to place in order to lengthen the telomeres.

In yeast, telomeres are decorated by a multi-protein complex called CST, which contains the proteins Cdc13 (C), Stn1 (S), and Ten1 (T). Cdc13 is a key member of that complex and serves both to cap the telomere structure and recruit key enzymes.

Skordalakes' newly determined structure demonstrates that, like three of the other four regions of Cdc13, OB2 adopts what is called an oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding fold (OB). These folds normally allow proteins to bind DNA or sugars, but OB2 does neither; its crystal structure indicates that this fold actually forms a large binding surface that helps two Cdc13 proteins to form a dimeric complex.

The authors then used biochemical analyses to determine that OB2 also does not directly bind the protein Stn1. Nevertheless, full-length Cdc13 OB2 mutants deficient in dimerization are also deficient in Stn1 recruitment. When the team inserted strategic Cdc13 mutations into yeast, they found that the cells had abnormally long telomeres, probably as a result of disrupted CST complex assembly caused by impaired Cdc13 dimerization.

"The dimerization of OB2 is required for the proper assembly of the CST complex at the telomeres," Skordalakes says. "When you disrupt oligomerization of this domain, you disrupt assembly of this complex, and thus regulation of telomere length."

###

The study was funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, the V Foundation, the Emerald Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute on Aging.

Co-authors include Sandy Harper, David Schultz, Ph.D., and David Speicher, Ph.D., from The Wistar Institute; and Mark Mason, Jennifer Wanat, Ph.D., and F. Brad Johnson, M.D., Ph.D., from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

It takes two to tangle: Wistar scientists further unravel telomere biology

2012-11-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pathway identified in human lymphoma points way to new blood cancer treatments

2012-11-21

PHILADELPHIA – A pathway called the "Unfolded Protein Response," or UPR, a cell's way of responding to unfolded and misfolded proteins, helps tumor cells escape programmed cell death during the development of lymphoma.

Research, led by Lori Hart, Ph.D., research associate and Constantinos Koumenis, Ph.D., associate professor,and research division director in the Department of Radiation Oncology, both from the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Davide Ruggero, Ph.D., associate professor, Department of Urology, University of California, San Francisco, ...

University of Tennessee study: Unexpected microbes fighting harmful greenhouse gas

2012-11-21

The environment has a more formidable opponent than carbon dioxide. Another greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide, is 300 times more potent and also destroys the ozone layer each time it is released into the atmosphere through agricultural practices, sewage treatment and fossil fuel combustion.

Luckily, nature has a larger army than previously thought combating this greenhouse gas—according to a study by Frank Loeffler, University of Tennessee, Knoxville–Oak Ridge National Laboratory Governor's Chair for Microbiology, and his colleagues.

The findings are published in the ...

Saving water without hurting peach production

2012-11-21

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists are helping peach growers make the most of dwindling water supplies in California's San Joaquin Valley.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist James E. Ayars at the San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center in Parlier, Calif., has found a way to reduce the amount of water given post-harvest to early-season peaches so that the reduction has a minimal effect on yield and fruit quality. ARS is USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency, and the research supports the USDA priority of promoting international ...

Better protection for forging dies

2012-11-21

Forging dies must withstand a lot. They must be hard so that their surface does not get too worn out and is able to last through great changes in temperature and handle the impactful blows of the forge. However, the harder a material is, the more brittle it becomes - and forging dies are less able to handle the stress from the impact. For this reason, the manufacturers had to find a compromise between hardness and strength. One of the possibilities is to surround a semi-hard, strong material with a hard layer. The problem is that the layer rests on the softer material and ...

CDC and NIH survey provides first report of state-level COPD prevalence

2012-11-21

The age-adjusted prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) varies considerably within the United States, from less than 4 percent of the population in Washington and Minnesota to more than 9 percent in Alabama and Kentucky. These state-level rates are among the COPD data available for the first time as part of the newly released 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey.

"COPD is a tremendous public health burden and a leading cause of death. It is a health condition that needs to be urgently addressed, particularly on a local level," ...

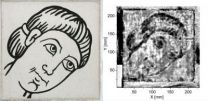

Detective work using terahertz radiation

2012-11-21

It was a special moment for Michael Panzner of the Fraunhofer Institute for Material and Beam Technology IWS in Dresden, Germany and his partners: in the Dresden Hygiene Museum the scientists were examining a wall picture by Gerhard Richter that had been believed lost long ago. Shortly before leaving the German Democratic Republic the artist had left it behind as a journeyman's project. Then, in the 1960s, it was unceremoniously painted over. However, instead of being interested in the picture, Panzer was far more interested in the new detector which was being used for ...

Architecture of rod sensory cilium disrupted by mutation

2012-11-21

HOUSTON – (Nov. 22, 2012) – Using a new technique called cryo-electron tomography, two research teams at Baylor College of Medicine (www.bcm.edu) have created a three-dimensional map that gives a better understanding of how the architecture of the rod sensory cilium (part of one type of photoreceptor in the eye) is changed by genetic mutation and how that affects its ability to transport proteins as part of the light-sensing process.

Almost all mammalian cells have cilia. Some are motile and some are not. They play a central role in cellular operations, and when they ...

New evidence of dinosaurs' role in the evolution of bird flight

2012-11-21

Academics at the Universities of Bristol, Yale and Calgary have shown that prehistoric birds had a much more primitive version of the wings we see today, with rigid layers of feathers acting as simple airfoils for gliding.

Close examination of the earliest theropod dinosaurs suggests that feathers were initially developed for insulation, arranged in multiple layers to preserve heat, before their shape evolved for display and camouflage.

As evolution changed the configuration of the feathers, their important role in the aerodynamics and mechanics of flight became more ...

New Informatics and Bioimaging Center combines resources, expertise from UMD, UMB

2012-11-21

ADELPHI, Md. – A new center that combines advanced computing resources at the University of Maryland, College Park (UMD) with clinical data and biomedical expertise at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) could soon revolutionize the efficiency and effectiveness of health care in the state of Maryland and beyond.

The Center for Health-related Informatics and Bioimaging (CHIB) announced today joins computer scientists, life scientists, engineers, physicists, biostatisticians and others at the College Park campus with imaging specialists, physicians, clinicians ...

Wormholes from centuries-old art prints reveal the history of the 'worms'

2012-11-21

By examining art printed from woodblocks spanning five centuries, Blair Hedges, a professor of biology at Penn State University, has identified the species responsible for making the ever-present wormholes in European printed art since the Renaissance. The hole-makers, two species of wood-boring beetles, are widely distributed today, but the "wormhole record," as Hedges calls it, reveals a different pattern in the past, where the two species met along a zone across central Europe like a battle line of two armies. The research, which is the first of its kind to use printed ...