(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

Princeton University researchers developed an enhanced approach to capturing changes on the Earth's surface via satellite that could provide a more accurate account of how geographic areas change as a...

Click here for more information.

An enhanced approach to capturing changes on the Earth's surface via satellite could provide a more accurate account of how ice sheets, river basins and other geographic areas are changing as a result of natural and human factors. In a first application, the technique revealed sharper-than-ever details about Greenland's massive ice sheet, including that the rate at which it is melting might be accelerating more slowly than predicted.

Princeton University researchers developed a mathematical framework and a computer code to accurately capture ground-level conditions collected on particular geographic regions by the GRACE satellites (Gravity Recovery And Climate Experiment), according to a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. A joint project of NASA and the German Aerospace Center, GRACE measures gravity to depict how mass such as ice or water is distributed over the Earth's surface. A change in GRACE data can signify a change in mass, such as a receding glacier.

Typically, GRACE data are recorded for the whole globe and processed to remove large regional differences, said lead author Christopher Harig, a postdoctoral research associate in Princeton's Department of Geosciences. The result is a coarse image that can provide a general sense of mass change, but not details such as various mass fluctuations within an area.

With their method, Harig and co-author Frederik Simons, an assistant professor of geosciences, can clean up data "noise" — the signal variations and distortions that can obscure satellite readings — and then recover the finer surface details hidden within. From this, they can configure regional information into a high-resolution map that depicts the specific areas where mass change is happening and to what degree.

"We try to do very little processing to the data and stay closer to the real signal," Simons said. "GRACE data contain a lot of signals and a lot of noise. Our technique learns enough about the noise to effectively recover the signal, and at much finer spatial scales than was possible before. We can 'see through' the noise and recover the 'true' geophysical information contained in these data. We can now revisit GRACE data related to areas such as river basins and irrigation and soil moisture, not just ice sheets."

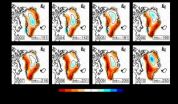

The researchers tested their method on GRACE data for Greenland recorded from 2003 to 2010 and brought the complexities of the island's glaciers into clearer focus. While overall ice loss on Greenland consistently increased between 2003 and 2010, Harig and Simons found that it was in fact very patchy from region to region.

In addition, the enhanced detail of where and how much ice melted allowed the researchers to estimate that the annual acceleration in ice loss is much lower than previous research has suggested, roughly increasing by 8 billion tons every year. Previous estimates were as high as 30 billion tons more per year.

Douglas MacAyeal, a geophysical sciences professor at the University of Chicago, said that the research provides a standardized and accurate method for translating GRACE data, particularly for ice sheets. The sprawling, incomplete nature of the satellite's information has spawned a myriad of approaches to interpreting it, some unique to specific scientists, he said.

"GRACE data is notoriously noisy and spatially spread out, and this has resulted in 'ad hoc' methods for processing mass changes of Earth's ice sheets that have wildly different values," said MacAyeal, who is familiar with the Princeton work but had no role in it.

"In other words, each particular investigator ends up getting a different individual number for the net change in mass," he said. "What this research does is figure out a way to be more thoughtful and purposeful about exactly how to deal with GRACE's notorieties. This method would allow researchers to standardize a bit more and also to understand more precisely where they are, and where they are not, able to resolve ice changes."

Simons compared the noise that previously obscured a precise view of Greenland's glaciers to fog on a window. For a small area such as Greenland, the GRACE signal can be easily overwhelmed by noise, which has numerous causes such as the satellite's orbital position or even the type of mathematics researchers use to interpret data, Simons said.

"Other researchers used less than perfect tools to wipe off the window more or less indiscriminately and quite literally left streaks on the data. They were thus less able to put the continent into the proper focus," he said.

"We effectively modeled then removed noise to get the ice-loss signal out of the data," Simons said. "We then recovered relatively tiny variations in ice mass that to others might have looked like noise, but that to us were shown to be signal."

The Princeton researchers found that Greenland lost roughly 200 billion tons of ice each year during the seven-year period studied, which falls within the range reported by other studies. The amount of ice lost annually could stack up on all of Manhattan to nearly 12,000 feet, or more than eight times taller than the Empire State Building, Harig said.

As expected, ice loss occurred in the lower, warmer coastal areas — as opposed to the higher and colder interior, which gained ice mass — but the melt was concentrated on the southeast and northwest coasts for most of the period studied. Indeed, many coastal areas showed no ice-mass loss, while the ice sheet on the southwest coast actually thickened slightly from 2003 to 2006.

But these trends were more complex when Harig and Simons got into the details. Surprisingly, the location of the greatest melt activity migrated around the island, shifting from the southeast to the northwest coast in just a few years. Ice loss on the southeast coast built up starting in 2003 and hit a highpoint in 2007. In 2008, loss on this coast began to recede and shift toward the northwest coast; by 2010, the southeast coast displayed only minor ice loss, while nearly the entire western coast exhibited the most severe melt. During this transition, melt also receded then picked up again on the northeastern coast with seemingly little overlap with activity elsewhere.

Details such as these can help scientists better understand the interplay between Greenland's glaciers and factors that influence melt such as ocean temperature, daily sunshine and cloud coverage, Harig said. That understanding can in turn help researchers determine how the Greenland ice sheet responds to climate change — and how much more ice loss to expect. At current melt rates, the Greenland ice sheet would take about 13,000 years to melt completely, which would result in a global sea-level rise of more than 21 feet (6.5 meters), Harig said.

"Scientists are not totally sure what the driving force of the melt on Greenland is on short, yearly timescales," Harig said. "There is no certainty about which outside factor is the most important or if all of them contribute. Being able to compare what is happening regionally to field observations from other researchers of what a glacier is doing helps us figure out what is causing all this melt."

Michael Oppenheimer, Princeton's Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs, said that the new level of detail Harig and Simons provide on Greenland's glaciers not only gives insight into what is causing the glaciers to melt, but what could possibly happen if they do.

Unlike water in a bathtub, sea-level rise is not uniform, said Oppenheimer, who is familiar with the research but had no role in it. Higher waters in certain locations may depend on which part of an ice sheet melts, he said. And determining which part of an ice sheet is melting the most requires precise details of ice loss and gain for specific glaciers — details that have largely been unavailable, Oppenheimer said.

"Nobody has really been able to take a look at an individual ice sheet and determine the influence that ice loss from different parts of that ice sheet could have on sea levels," Oppenheimer said.

"The details matter. Being able to pinpoint where and how much ice gain and loss there is tells you something about the driving forces behind it, and therefore how much we can expect in the future," he said. "A synoptic view at a high resolution is what GRACE always promised, and now this research has helped realize that potential. It's time to finally milk the data for as much detail as possible."

Harig is adapting the computer code — which is available online — to study GRACE data on ice loss in Antarctica and water accumulation in the Amazon River basin.

The paper, "Mapping Greenland's mass loss in space and time," was published online Nov. 19 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

INFORMATION:

[Video and images can be seen at http://www.princeton.edu/main/news/archive/S35/40/38C46. To obtain high-res images, contact Princeton science writer Morgan Kelly, (609) 258-5729, mgnkelly@princeton.edu]

Princeton research: Embracing data 'noise' brings Greenland's complex ice melt into focus

2012-11-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Fountain of youth' technique rejuvenates aging stem cells

2012-11-28

Toronto, ON (27 November, 2012) -- A new method of growing cardiac tissue is teaching old stem cells new tricks. The discovery, which transforms aged stem cells into cells that function like much younger ones, may one day enable scientists to grow cardiac patches for damaged or diseased hearts from a patient's own stem cells—no matter what age the patient—while avoiding the threat of rejection.

Stem cell therapies involving donated bone marrow stem cells run the risk of patient rejection in a portion of the population, argues Milica Radisic, Canada Research Chair in ...

How vegetables make the meal

2012-11-28

Parents may have some new motivations to serve their kids vegetables. A new Cornell University study, published in Public Health Nutrition, found that by simply serving vegetables with dinner, the main course would taste better and the preparer was perceived to be more thoughtful and attentive.

"Most parents know that vegetables are healthy, yet vegetables are served at only 23% of American dinners," said lead author Brian Wansink, PhD, the John Dyson Professor of Marketing and Consumer Behavior at Cornell University. "If parents knew that adding vegetables to the plate ...

GSA Bulletin: From Titan to Tibet

2012-11-28

Boulder, Colo., USA – GSA Bulletin articles posted online between 2 October and 21 November span locations such as the San Andreas fault, California; Tibet; Mongolia; Maine; the Owyhee River, Oregon; the Afar Rift, Ethiopia; Wyoming; Argentina; the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt; British Columbia; the southern Rocky Mountains; Scandinavia; and Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Topics include the "big crisis" in the history of life on Earth; the structural geology of Mount St. Helens; and the evolution of a piggyback basin.

GSA Bulletin articles published ahead of print are online ...

NASA's TRMM satellite confirms 2010 landslides

2012-11-28

A NASA study using TRMM satellite data revealed that the year 2010 was a particularly bad year for landslides around the world.

A recent NASA study published in the October issue of the Journal of Hydrometeorology compared satellite rain data from NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission (TRMM) to landslides in central eastern China, Central America and the Himalayan Arc, three regions with diverse climates and topography where rainfall-triggered landslides are frequent and destructive hazards to the local populations.

The work, led by Dalia Kirschbaum, a research ...

Fast forward to the past: NASA technologists test 'game-changing' data-processing technology

2012-11-28

It's a digital world. Or is it?

NASA technologist Jonathan Pellish isn't convinced. In fact, he believes a computing technology of yesteryear could potentially revolutionize everything from autonomous rendezvous and docking to remotely correcting wavefront errors on large, deployable space telescope mirrors like those to fly on the James Webb Space Telescope.

"It's fast forward to the past," Pellish said, referring to an emerging processing technology developed by a Cambridge, Mass.-based company, Analog Devices Lyric Labs.

So convinced is he of its potential, Pellish ...

NASA sees Tropical Storm Bopha intensifying in Micronesia

2012-11-28

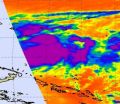

Tropical storm warnings are in effect in Micronesia as NASA and other satellite imagery indicates that Tropical Storm Bopha continues to intensify.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured an infrared image of Tropical Storm Bopha on Nov. 27 at 0241 UTC that indicated a lot of power exists in the strengthening tropical storm. The AIRS image captured the eastern half of the tropical storm and showed a large area of very cold, very high cloud tops, where temperatures colder than -63 Fahrenheit (-52 Celsius) have ...

High altitude climbers at risk for brain bleeds

2012-11-28

CHICAGO – New magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) research shows that mountain climbers who experience a certain type of high altitude sickness have traces of bleeding in the brain years after the initial incident, according to a study presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

High altitude cerebral edema (HACE) is a severe and often fatal condition that can affect mountain climbers, hikers, skiers and travelers at high altitudes—typically above 7,000 feet, or 2,300 meters.

HACE results from swelling of brain tissue due ...

Most patients in the dark about what radiologists do

2012-11-28

CHICAGO – The role of radiologists in healthcare has long been poorly understood among the general public, but new research presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) shows that even patients who've had imaging exams in the past know little about the profession.

Researchers said the study findings highlight an opportunity for radiologists to educate the public about their role in healthcare.

"We know from previous studies that about half of the general public doesn't even know that radiologists are physicians," said Peter ...

Men with belly fat at risk for osteoporosis

2012-11-28

CHICAGO – Visceral, or deep belly, obesity is a risk factor for bone loss and decreased bone strength in men, according to a study presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

"It is important for men to be aware that excess belly fat is not only a risk factor for heart disease and diabetes, it is also a risk factor for bone loss," said Miriam Bredella, M.D., radiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

According to the National Center for Health ...

CT depicts racial differences in coronary artery disease

2012-11-28

CHICAGO – While obesity is considered a cardiovascular risk factor, a study presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) showed that African-American patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) have much less fat around their hearts compared to Caucasian patients.

"Prior evidence suggests that increased fat around the heart may be either an independent marker of CAD burden or a predictor of the future risk of acute coronary events," said U. Joseph Schoepf, M.D., professor of radiology and medicine and director of cardiovascular ...