(Press-News.org) Every kid knows that giant carnivores like Tyrannosaurus rex dominated the Cretaceous period, but they weren't the only big guys in town. Giant plant-eating theropods – close relatives of both T. rex and today's birds – also lived and thrived alongside their meat-eating cousins. Now researchers have started looking at why dinosaurs that abandoned meat in favor of vegetarian diets got so big, and their results may call conventional wisdom about plant-eaters and body size into question.

Scientists have theorized that bigger was better when it came to plant eaters, because larger digestive tracts would allow dinosaurs to maximize the nutrition they could extract from high-fiber, low-calorie food. Therefore, natural selection may have favored increasing body sizes in groups of animals that went meatless.

Three groups of giant feathered theropods from the Cretaceous period seemed to follow that rule of thumb – the biggest specimens were also the plant-eaters. Lindsay Zanno, research assistant professor of biology at North Carolina State University and director of the Paleontology & Geology Research Lab at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, and Peter Makovicky, associate curator of paleontology at the Field Museum in Chicago, decided to see if diet was the determining factor when it came to size. Makovicky notes that "Having three closely related lineages of dinosaurs adapting to herbivory over the same geological time span and showing evidence of increasing size provided a near perfect test case."

Zanno and Makovicky estimated body mass for 47 extinct species of feathered dinosaur, representing three major groups that abandoned a strictly meat-eating diet – ornithomimosaurs ("bird-mimics"), oviraptorosaurs ("egg-thieves"), and the bizarre therizinosaurs ("scythe-lizards"). Most species in these lineages also possessed a toothless beak, three-toed feet, and shorter tails than your average dinosaur, making them look a lot like modern birds.

All three groups evolved gigantic proportions: the largest oviraptorosaur weighed over 7,000 pounds, and the biggest ornithomimosaurs and therizinosaurs topped out at over 13,000 pounds. "The largest feathered dinosaurs were more than 100 times more massive than your average person," says Zanno. "The reality is that for most of us, it is downright difficult to imagine a feathered animal of gigantic proportions."

The researchers also found that average body mass did increase in these groups over time (on average, the earliest members were smallest and the last species to evolve were among the largest). But this simple correlation didn't indicate whether large size was an evolutionary advantage.

To test whether these groups were being driven to get bigger by natural selection, Zanno and Makovicky fitted different evolutionary models to the data, looking to see which model best described the patterns of body mass from ancestor species to descendant species. They found that these theropod groups were experimenting with different body masses as they evolved, with some getting bigger, while others were getting smaller. In short, there was no clear-cut drive to get big – size seemed to provide no overwhelming advantage during the evolution of these animals.

The researchers' results appear in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"Results of our study don't rule out diet as affecting body mass, but do seem to indicate that fluctuating environmental conditions over time were trumping the benefit of becoming a giant," Zanno says. "The long and short of it is that for plant-eating theropods, bigger wasn't always better."

"Where resources permitted, these animals could get as big as elephants, but that clearly was not the case in all environments and time periods," says Makovicky. "Factors such as resource abundance and competition with other herbivores likely played a more significant role." He added that uneven sampling in the fossil record, such as preferential preservation of smaller species in earlier time periods and larger species in later ones, could also impact the results.

INFORMATION:

Note to editors: Abstract of the paper follows

"No evidence for directional evolution of body mass in herbivorous theropod dinosaurs"

Authors: Lindsay E. Zanno, Department of Biology, North Carolina State University, Paleontology and Geology Laboratory, Nature Research Center, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Department of Geology, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL; Peter J Makovicky, Department of Geology, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL

Published: Proceedings of the Royal Society B

Abstract:

The correlation between large body size and digestive efficiency has been hypothesized to have driven trends of increasing mass in herbivorous clades by means of directional selection. Yet, to date, few studies have investigated this relationship from a phylogenetic perspective and none, to our

knowledge, with regard to trophic shifts. Here, we reconstruct body mass in the three major subclades of non-avian theropod dinosaurs whose ecomorphology is correlated with extrinsic evidence of at least facultative herbivory in the fossil record – all of which also achieve relative gigantism (more than 3000 kg). Ordinary least-squares regressions on natural logtransformed mean mass recover significant correlations between increasing mass and geologic time. However, tests for directional evolution in body mass find no support for a phylogenetic trend, instead favouring passive models of trait evolution. Cross-correlation of sympatric taxa from five localities in Asia reveals that environmental influences such as differential habitat sampling and/or taphonomic filtering affect the preserved record of dinosaurian body mass in the Cretaceous. Our results are congruent with studies documenting that behavioural and/or ecological factors may mitigate the benefit of increasing mass in extant taxa, and suggest that the hypothesis can be extrapolated to herbivorous lineages across geologic time scales.

For some feathered dinosaurs, bigger not necessarily better

2012-11-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Compound found in rosemary protects against macular degeneration in laboratory model

2012-11-28

LA JOLLA, Calif., November 27, 2012 – Herbs widely used throughout history in Asian and early European cultures have received renewed attention by Western medicine in recent years. Scientists are now isolating the active compounds in many medicinal herbs and documenting their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. In a study published in the journal Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, Stuart A. Lipton, M.D., Ph.D. and colleagues at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham) report that carnosic acid, a component of the herb rosemary, promotes ...

Increasing drought stress challenges vulnerable hydraulic system of plants, GW professor finds

2012-11-28

WASHINGTON - The hydraulic system of trees is so finely-tuned that predicted increases in drought due to climate change may lead to catastrophic failure in many species. A recent paper co-authored by George Washington University Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences Amy Zanne finds that those systems in plants around the globe are operating at the top of their safety threshold, making forest ecosystems vulnerable to increasing environmental stress.

In the current issue of the journal Nature, Dr. Zanne and lead authors from the University of Western Sydney in Australia ...

GSA Today: Human transformation of land threatens future sustainability?

2012-11-28

Boulder, Colorado, USA - Social and physical scientists have long been concerned about the effects of humans on Earth's surface -- in part through deforestation, encroachment of urban areas onto traditionally agricultural lands, and erosion of soils -- and the implications these changes have on Earth's ability to provide for an ever-growing population. The December 2012 GSA Today science article presents examples of land transformation by humans and documents some of the effects of these changes.

Researchers Roger Hooke of the University of Maine, USA, and José F. Martín-Duque ...

Resolving conflicts over end-of-life care: Mayo experts offer tips

2012-11-28

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- It's one of the toughest questions patients and their loved ones can discuss with physicians: When is further medical treatment futile? The conversation can become even more difficult if patients or their families disagree with health care providers' recommendations on end-of-life care. Early, clear communication between patients and their care teams, choosing objective surrogates to represent patients and involving third parties such as ethics committees can help avoid or resolve conflicts, Mayo Clinic experts Christopher Burkle, M.D., J.D., and Jeffre ...

How to buy an ethical diamond

2012-11-28

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- You've already decided that you're going to pop the question. Now comes another quandary: Where to get the ring, if you're buying one?

The holidays are a busy time for engagements, and Trina Hamilton, a University at Buffalo expert in corporate responsibility, says socially minded consumers have a lot to think about when it comes to finding the right rock.

In recent years, shoppers have turned to Canadian diamonds as news reports and movies exposed the diamond trade's role in fueling armed conflicts in developing countries. (Think "Blood Diamond," the ...

East Asia faces unique challenges, opportunities for stem cell innovation

2012-11-28

Tension is the theme running through the new consensus statement issued by the Hinxton Group, an international working group on stem cell research and regulation. Specifically, tension between intellectual property policies and scientific norms of free exchange, but also between eastern and western cultures, national and international interests, and privatized vs. nationalized health care systems.

The consensus, titled Statement on Data and Materials Sharing and Intellectual Property in Pluripotent Stem Cell Science in Japan and China, was released on the Hinxton Group's ...

Reducing sibling rivalry in youth improves later health and well-being

2012-11-28

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Sibling conflict represents parents' number one concern and complaint about family life, but a new prevention program -- designed and carried out by researchers at Penn State -- demonstrates that siblings of elementary-school age can learn to get along. In doing so, they can improve their future health and well-being.

"Negative sibling relationships are strongly linked to aggressive, anti-social and delinquent behaviors, including substance use," said Mark Feinberg, research professor in the Prevention Research Center for the Promotion of Human ...

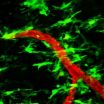

NIH-funded researchers show possible trigger for MS nerve damage

2012-11-28

High-resolution real-time images show in mice how nerves may be damaged during the earliest stages of multiple sclerosis. The results suggest that the critical step happens when fibrinogen, a blood-clotting protein, leaks into the central nervous system and activates immune cells called microglia.

"We have shown that fibrinogen is the trigger," said Katerina Akassoglou, Ph.D., an associate investigator at the Gladstone Institute for Neurological Disease and professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and senior author of the paper published ...

Rocks, water, air, space ... and humans: An NSF recipe for AGU success

2012-11-28

The National Science Foundation is suggesting adding a bit of spice to a geophysical scientist's research recipe of rocks, water, air, space and life:

Humans.

At next month's Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) a behemoth of a conference of nearly 20,000 Earth and space scientists, educators, students and policy makers, an international group of scientists will make the case for adding the human element to their research.

The International Network of Research in Coupled Human and Natural Systems – CHANS-Net – is supported by the National Science ...

Kentucky study finds common drug increases deaths in atrial fibrillation patients

2012-11-28

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Nov. 27, 2012) -- Digoxin, a drug widely used to treat heart disease, increases the possibility of death when used by patients with a common heart rhythm problem − atrial fibrillation (AF), according to new study findings by University of Kentucky researchers. The results have been published in the prestigious European Heart Journal, and raises serious concerns about the expansive use of this long-standing heart medication in patients with AF.

UK researchers led by Dr. Samy Claude Elayi, associate professor of medicine at UK HealthCare's Gill Heart ...