(Press-News.org) Scientists at NYU Langone Medical Center have identified two genes involved in establishing the neuronal circuits required for breathing. They report their findings in a study published in the December issue of Nature Neuroscience. The discovery, featured on the journal's cover, could help advance treatments for spinal cord injuries and neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which gradually kill neurons that control the movement of muscles needed to breathe, move, and eat.

The study identifies a molecular code that distinguishes a group of muscle-controlling nerve cells collectively known as the phrenic motor column (PMC). These cells lie about halfway up the back of the neck, just above the fourth cervical vertebra, and are "probably the most important motor neurons in your body," says Jeremy Dasen, PhD, assistant professor of physiology and neuroscience and a member of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, who led the three-year study with Polyxeni Philippidou, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow.

Harming the part of the spinal cord where the PMC resides can instantly shut down breathing. But relatively little is known about what distinguishes PMC neurons from neighboring neurons, and how PMC neurons develop and wire themselves to the diaphragm in the fetus.

The PMC cells relay a constant flow of electrochemical signals down their bundled axons and onto the diaphragm muscles, allowing the lungs to expand and relax in the natural rhythm of breathing. "We now have a set of molecular markers that distinguish those cells from other populations of motor neurons, so that we can study them in detail and look for ways to selectively enhance their survival," Dr. Dasen says. Degeneration of PMC neurons is the primary cause of death in patients with ALS and spinal cord injuries.

To find out what distinguishes PMC neurons from their spinal neighbors in mice, Dr. Philippidou injected a retrograde fluorescent tracer into the phrenic nerve, which wires the PMC to the diaphragm, and then looked for the spinal neurons that lit up as the tracer worked its way back to the PMC. He used transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in motor neurons and their axons in order to see the phrenic nerve. After noting the characteristic gene expression pattern of these PMC neurons, Dr. Philippidou began to determine their specific roles. Ultimately, a complicated strain of transgenic mice, based partly on mice supplied by collaborator Lucie Jeannotte, PhD, at the University of Laval in Quebec, revealed two genes, Hoxa5 and Hoxc5, as the prime controllers of proper PMC development. Hox genes (39 are expressed in humans) are well known as master gene regulators of animal development.

When Hoxa5 and Hoxc5 are silenced in embryonic motor neurons in mice, the scientists reported, the PMC fails to form its usual, tightly columnar organization and doesn't connect correctly to the diaphragm, leaving a newborn animal unable to breathe. "Even if you delete these genes late in fetal development, the PMC neuron population drops and the phrenic nerve doesn't form enough branches on diaphragm muscles," Dr. Dasen says.

Dr. Dasen plans to use the findings to help understand the wider circuitry of breathing—including rhythm-generating neurons in the brain stem, which are in turn responsive to carbon dioxide levels, stress, and other environmental factors. "Now that we know something about PMC cells, we can work our way through the broader circuit, to try to figure out how all those connections are established," he says.

"Once we understand how the respiratory network is wired we can begin to develop novel treatment options for breathing disorders such as sleep apneas," adds Dr. Philippidou.

In late October Dr. Dasen lost many of his transgenic mice when Hurricane Sandy flooded the basement of the Smilow building at NYU Langone Medical Center. But just before the hurricane hit, he sent an important group of these mice back to Dr. Jeannotte in Quebec, "so we didn't lose everything," he says.

###

A commentary about the study appears in the issue at http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v15/n12/full/nn.3272.html

About NYU Langone Medical Center

NYU Langone Medical Center, a world-class, patient-centered, integrated, academic medical center, is one of the nation's premier centers for excellence in clinical care, biomedical research and medical education. Located in the heart of Manhattan, NYU Langone is composed of four hospitals – Tisch Hospital, its flagship acute care facility; the Hospital for Joint Diseases, recognized as one of the nation's leading hospitals dedicated to orthopaedics and rheumatology; Hassenfeld Pediatric Center, a comprehensive pediatric hospital supporting a full array of children's health services; and Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, the world's first university-affiliated facility devoted entirely to rehabilitation medicine – plus NYU School of Medicine, which since 1841 has trained thousands of physicians and scientists who have helped to shape the course of medical history. The medical center's tri-fold mission to serve, teach and discover is achieved 365 days a year through the seamless integration of a culture devoted to excellence in patient care, education and research. For more information, go to www.NYULMC.org.

Scientists describe the genetic signature of a vital set of neurons

Findings could advance treatments for spinal cord injuries, ALS

2012-11-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Predicting material fatigue

2012-11-30

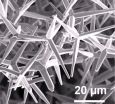

The scientists of Kiel University, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and the Technische Universität München (TUM) have published their results in the current issue of the journal Advanced Materials.

"The luminescent features of zinc oxide tetrapod crystals are well established. According to our work hypothesis, these characteristics showed pronounced variations under a mechanical load, and we realised that it could help to detect internal damages of composite materials", says Dr. Yogendra Mishra of Kiel University's Technical Faculty. In one experiment, the scientists ...

Young surgeons face special concerns with operating room distractions

2012-11-30

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A study has found that young, less-experienced surgeons made major surgical mistakes almost half the time during a "simulated" gall bladder removal when they were distracted by noises, questions, conversation or other commotion in the operating room.

In this analysis, eight out of 18, or 44 percent of surgical residents made serious errors, particularly when they were being tested in the afternoon. By comparison, only one surgeon made a mistake when there were no distractions.

Exercises such as this in what scientists call "human factors engineering" ...

A human-caused climate change signal emerges from the noise

2012-11-30

Livermore, Calif. -- By comparing simulations from 20 different computer models to satellite observations, Lawrence Livermore climate scientists and colleagues from 16 other organizations have found that tropospheric and stratospheric temperature changes are clearly related to human activities.

The team looked at geographical patterns of atmospheric temperature change over the period of satellite observations. The team's goal of the study was to determine whether previous findings of a "discernible human influence" on tropospheric and stratospheric temperature were sensitive ...

Delayed treatment for advanced breast cancer has 'profound effect'

2012-11-30

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Results from a new study conducted by researchers at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC-James) show women who wait more than 60 days to begin treatment for advanced breast cancer face significantly higher risks of dying than women who start therapy shortly after diagnosis.

"We wanted to see whether delaying treatment affected mortality rates among women with breast cancer," says Electra D. Paskett, associate director for population sciences at OSUCCC-James. ...

Diabetics with cancer dangerously ignore blood sugar

2012-11-30

CHICAGO --- When people with Type 2 diabetes are diagnosed with cancer -- a disease for which they are at higher risk -- they ignore their diabetes care to focus on cancer treatment, according to new Northwestern Medicine® research. But uncontrolled high blood sugar is more likely to kill them and impairs their immune system's ability to fight cancer.

However, people with Type 2 diabetes who received diabetes education after a cancer diagnosis were more likely to take care of their blood sugar. As a result, they had fewer visits to the emergency room, fewer hospital admissions, ...

Autism severity may stem from fear

2012-11-30

Most people know when to be afraid and when it's ok to calm down.

But new research on autism shows that children with the diagnosis struggle to let go of old, outdated fears. Even more significantly, the Brigham Young University study found that this rigid fearfulness is linked to the severity of classic symptoms of autism, such as repeated movements and resistance to change.

For parents and others who work with children diagnosed with autism, the new research highlights the need to help children make emotional transitions – particularly when dealing with their fears.

"People ...

Can life emerge on planets around cooling stars?

2012-11-30

Astronomers find planets in strange places and wonder if they might support life. One such place would be in orbit around a white or brown dwarf. While neither is a star like the sun, both glow and so could be orbited by planets with the right ingredients for life.

No terrestrial, or Earth-like planets have yet been confirmed orbiting white or brown dwarfs, but there is no reason to assume they don't exist. However, new research by Rory Barnes of the University of Washington and René Heller of Germany's Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam hints that planets orbiting ...

Working couples face greater odds of intimate partner violence

2012-11-30

HUNTSVILLE, TX (11/30/12) -- Intimate partner violence is two times more likely to occur in two income households, compared to those where only one partner works, a recent study at Sam Houston State University found.

The study, conducted by Cortney A. Franklin and Tasha A. Menaker and supported by the Crime Victims' Institute, was titled, "Differences in Education/Employment Status and Intimate Partner Victimization." It looked at the impact of education levels and employment status differences among heterosexual partners on intimate partner victimization. While differences ...

Proteins that work at the ends of DNA could provide cancer insight

2012-11-30

CHAMPAIGN, lll. — New insights into a protein complex that regulates the very tips of chromosomes could improve methods of screening anti-cancer drugs.

Led by bioengineering professor Sua Myong, the research group's findings are published in the journal Structure.

Myong's group focused on understanding the proteins that protect and regulate telomeres, segments of repeating DNA units that cap the ends of chromosomes. Telomeres protect the important gene-coding sections of DNA from loss or damage, the genetic equivalent of aglets – the covering at the tips of shoelaces ...

Defining career paths in health systems improvement

2012-11-30

The sheer number of efforts aimed at improving the quality and efficiency of the U.S. health care system – ranging from portions of the national Affordable Care Act to local programs at individual hospitals and practices – reflects the urgency and importance of the task. One aspect that has received inadequate attention, according to three physicians writing in the January 2013 issue of Academic Medicine, is training the next generation of experts needed to help lead these efforts. In their Perspective article, which has been released online, the authors propose a framework ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Weill Cornell Medicine selected for Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award

Largest high-precision 3D facial database built in China, enabling more lifelike digital humans

SwRI upgrades facilities to expand subsurface safety valve testing to new application

Iron deficiency blocks the growth of young pancreatic cells

Selective forest thinning in the eastern Cascades supports both snowpack and wildfire resilience

A sea of light: HETDEX astronomers reveal hidden structures in the young universe

Some young gamers may be at higher risk of mental health problems, but family and school support can help

Reduce rust by dumping your wok twice, and other kitchen tips

High-fat diet accelerates breast cancer tumor growth and invasion

Leveraging AI models, neuroscientists parse canary songs to better understand human speech

Ultraprocessed food consumption and behavioral outcomes in Canadian children

The ISSCR honors Dr. Kyle M. Loh with the 2026 Early Career Impact Award for Transformative Advances in Stem Cell Biology

The ISSCR honors Alexander Meissner with the 2026 ISSCR Momentum Award for exceptional work in developmental and stem cell epigenetics

The ISSCR honors stem cell COREdinates and CorEUstem with the 2026 ISSCR Public Service Award

Minimally invasive procedure effectively treats small kidney cancers

SwRI earns CMMC Level 2 cybersecurity certification

Doctors and nurses believe their own substance use affects patients

Life forms can planet hop on asteroid debris – and survive

Sylvia Hurtado voted AERA President-Elect; key members elected to AERA Council

Mount Sinai and King Saud University Medical City forge a three-year collaboration to advance precision medicine in familial inflammatory bowel disease

AI biases can influence people’s perception of history

Prenatal opioid exposure and well-being through adolescence

Big and small dogs both impact indoor air quality, just differently

Wearing a weighted vest to strengthen bones? Make sure you’re moving

Microbe survives the pressures of impact-induced ejection from Mars

Asteroid samples offer new insights into conditions when the solar system formed

Fecal transplants from older mice significantly improve ovarian function and fertility in younger mice

Delight for diastereomer production: A novel strategy for organic chemistry

Permafrost is key to carbon storage. That makes northern wildfires even more dangerous

Hairdressers could be a secret weapon in tackling climate change, new research finds

[Press-News.org] Scientists describe the genetic signature of a vital set of neuronsFindings could advance treatments for spinal cord injuries, ALS