(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, Calif., December 3, 2012 – An embryo is an amazing thing. From just one initial cell, an entire living, breathing body emerges, full of working cells and organs. It comes as no surprise that embryonic development is a very carefully orchestrated process—everything has to fall into the right place at the right time. Developmental and cell biologists study this very thing, unraveling the molecular cues that determine how we become human.

"One of the first, and arguably most important, steps in development is the allocation of cells into three germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—that give rise to all tissues and organs in the body," explains Mark Mercola, Ph.D., professor and director of Sanford-Burnham's Muscle Development and Regeneration Program in the Sanford Children's Health Research Center.

In a study published in the journal Genes & Development, Mercola and his team, including postdoctoral researcher Alexandre Colas, Ph.D., and Wesley McKeithan, discovered that microRNAs play an important role in this cell- and germ layer-directing process during development.

MicroRNA: one man's junk is another's treasure

MicroRNAs are small pieces of genetic material similar to the messenger RNA that carries protein-encoding recipes from a cell's genome out to the protein-building machinery in the cytoplasm. Only microRNAs don't encode proteins. So, for many years, scientists dismissed the regions of the genome that encode these small, non-protein coding RNAs as "junk."

We now know that microRNAs are far from junk. They may not encode their own proteins, but they do bind messenger RNA, preventing their encoded proteins from being constructed. In this way, microRNAs play important roles in determining which proteins are produced (or not produced) at a given time.

MicroRNAs are increasingly recognized as an important part of both normal cellular function and the development of human disease.

So, why not embryonic development, too?

Directing cellular traffic

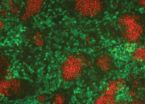

To pinpoint which—if any—microRNAs influence germ layer formation in early embryonic development, Mercola and his team individually studied most (about 900) of the microRNAs from the human genome. They tested each microRNA's ability to direct formation of mesoderm and endoderm from embryonic stem cells. In doing so, they discovered that two microRNA families—called let-7 and miR-18—block endoderm formation, while enhancing mesoderm and ectoderm formation.

The researchers confirmed their finding by artificially blocking let-7 function and checking to see what happened. That move dramatically altered embryonic cell fate, diverting would-be mesoderm and ectoderm into endoderm and underscoring the microRNA's crucial role in development.

But they still wanted to know more…how do let-7 and miR-18 work? Mercola's team went on to determine that these microRNAs direct mesoderm and ectoderm formation by dampening the TGFβ signaling pathway. TGFβ is a molecule that influences many cellular behaviors, including proliferation and differentiation. When these microRNAs tinker with TGFβ activity, they send cells on a certain course—some go on to become bone, others brain.

"We've now shown that microRNAs are powerful regulators of embryonic cell fate," Mercola says. "But our study also demonstrates that screening techniques, combined with systems biology, provide a paradigm for whole-genome screening and its use in identifying molecular signals that control complex biological processes."

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R33 HL088266 and R01 HL113601), and the American Heart Association.

Original paper:

Colas AR, McKeithan WL, Cunningham TJ, Bushway PJ, Garmire LX, Duester G, Subramaniam S, & Mercola M (2012). Whole-genome microRNA screening identifies let-7 and mir-18 as regulators of germ layer formation during early embryogenesis. Genes & development PMID: 23152446

About Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute

Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute is dedicated to discovering the fundamental molecular causes of disease and devising the innovative therapies of tomorrow. The Institute consistently ranks among the top five organizations worldwide for its scientific impact in the fields of biology and biochemistry (defined by citations per publication) and currently ranks third in the nation in NIH funding among all laboratory-based research institutes. Sanford-Burnham utilizes a unique, collaborative approach to medical research and has established major research programs in cancer, neurodegeneration, diabetes, and infectious, inflammatory, and childhood diseases. The Institute is especially known for its world-class capabilities in stem cell research and drug discovery technologies. Sanford-Burnham is a U.S.-based, non-profit public benefit corporation, with operations in San Diego (La Jolla), California and Orlando (Lake Nona), Florida. For more information, news, and events, please visit us at sanfordburnham.org.

'Junk DNA' drives embryonic development

Sanford-Burnham researchers discover that microRNAs play an important role in germ layer formation—the process that determines which cells become which organs during embryonic development

2012-12-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Grief is not a disease, but cancer is -- what about erectile dysfunction?

2012-12-03

"Understanding peoples' attitudes about whether states of being should be considered diseases can inform social discourse regarding a number of contentious social and health public policy issues," says Kari Tikkinen, MD, PhD, corresponding author of the FIND Survey.

All Finns think that myocardial infarction, breast cancer, malaria and pneumonia are diseases. People are equally unanimous that wrinkles, grief and homosexuality are not diseases. What about drug addiction or absence of sexual desire? Or erectile dysfunction, infertility or obesity?

"The word disease ...

Researchers confirm the 'Pinocchio Effect': When you lie, your nose temperature raises

2012-12-03

The University of Granada researchers are pioneers in the application of thermography to the field Psychology. Thermography is a technique based on determining body temperature.

When a person lies they suffer a "Pinocchio effect", which is an increase in the temperature around the nose and in the orbital muscle in the inner corner of the eye. In addition, when we perform a considerable mental effort our face temperature drops and when we have an anxiety attack our face temperature raises. These are some of the conclusions drawn in this pioneer study conducted at the University ...

BGI's ICG-7 and Bio-IT APAC provides updates on the latest genomics research to advance life science

2012-12-03

December 3, 2012, Hong Kong and Shenzhen, China – The 7th International Conference on Genomics and Bio-IT APAC 2012, organized by BGI, the world's largest genomics organization, successfully concluded with numerous updates on on-going research applying today's latest sequencing and bioinformatics technologies to a new paradigm of human diseases and to enhancing global agriculture development. The three-day conference, held in Hong Kong, also brought new insights into Bio-cloud and big data management. More than 300 participants attended this top-grade international conference.

The ...

Heart-warming memories: Nostalgia can make you feel warmer

2012-12-03

As the nights draw in and the temperature begins to drop, many of us will be thinking of ways to warm up on the dark winter nights. However, few would think that remembering days gone by would be an effective way of keeping warm.

But research from the University of Southampton has shown that feeling nostalgic can make us feel warmer.

The study, published in the journal Emotion, investigated the effects of nostalgic feelings on reaction to cold and the perception of warmth. The volunteers, from universities in China and the Netherlands, took part in one of five studies. ...

Genes link growth in the womb with adult metabolism and disease

2012-12-03

Researchers have identified four new genetic regions that influence birth weight, providing further evidence that genes as well as maternal nutrition are important for growth in the womb. Three of the regions are also linked to adult metabolism, helping to explain why smaller babies have higher rates of chronic diseases later in life.

It has been known for some time that babies born with a lower birth weight are at higher risk of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Three genetic regions have already been identified that influence birth ...

An innovation will attach patients' electronic medical record to the foot of their hospital bed

2012-12-03

This press release is available in Spanish.

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) present tremendous potential in the field of healthcare, according to the researchers. "ICTs are going to contribute to a change in focus in aid and health services," comments Jesús Espinosa, CEO of IonIDE Telematics. According to accreditation and standardization associations, Spain is a leader in the management of clinical processes, because it has the greatest number of hospitals that have adopted electronic medical record (EMR). This computerized registry of patients' social, ...

Corn: Many active genes - high yield

2012-12-03

Hybrid plants provide much higher yield than their homozygous parents. Plant breeders have known this for more than 100 years and used this effect called heterosis for richer harvests. Until now, science has puzzled over the molecular processes underlying this phenomenon. Researchers at the University of Bonn and partners from Tübingen and the USA have now decoded one possible mechanism in corn roots. More genes are active in hybrid plants than in their homozygous parents. This might increase growth and yield of the corn plants. The results are published in the renowned ...

Have Venusian volcanoes been caught in the act?

2012-12-03

Six years of observations by ESA's Venus Express have shown large changes in the sulphur dioxide content of the planet's atmosphere, and one intriguing possible explanation is volcanic eruptions.

The thick atmosphere of Venus contains over a million times as much sulphur dioxide as Earth's, where almost all of the pungent, toxic gas is generated by volcanic activity.

Most of the sulphur dioxide on Venus is hidden below the planet's dense upper cloud deck, because the gas is readily destroyed by sunlight.

That means any sulphur dioxide detected in Venus' upper atmosphere ...

Malaria parasite's masquerade ball could be coming to an end

2012-12-03

More than a million people die each year of malaria caused by different strains of the Plasmodium parasite transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito. The medical world has yet to find an effective vaccine against the deadly parasite, which mainly affects pregnant women and children under the age of five. By figuring out how the most dangerous strain evades the watchful eye of the immune system, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have now paved the way for the development of new approaches to cure this acute infection.

Upon entering the bloodstream, the Plasmodium ...

BU, VA study describes 68 CTE cases in veterans, high school, college and pro athletes

2012-12-03

(BOSTON) – A study done by investigators at the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (CSTE) and the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, in collaboration with the Sports Legacy Institute (SLI), describes 68 cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) among deceased athletes and military veterans whose brain and spinal cords were donated to the VA CSTE Brain Bank. Of the 68 cases, 34 were former professional football players, nine had played only college football, and six had played only high school football. The results, which will ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel materials design approach achieves a giant cooling effect and excellent durability in magnetic refrigeration materials

PBM markets for Medicare Part D or Medicaid are highly concentrated in nearly every state

Baycrest study reveals how imagery styles shape pathways into STEM and why gender gaps persist

Decades later, brain training lowers dementia risk

Adrienne Sponberg named executive director of the Ecological Society of America

Cells in the ear that may be crucial for balance

Exploring why some children struggle to learn math

Math learning disability affects how the brain tackles problems, Stanford Medicine study shows

Dana-Farber research helps drive FDA label update for primary CNS lymphoma

Deep-sea microbes get unexpected energy boost

Coffee and tea intake, dementia risk, and cognitive function

Impact of a smartwatch hypertension notification feature for population screening

Glaciers in retreat: Uncovering tourism’s contradictions

Why melting glaciers are drawing more visitors and what that says about climate change

Mount Sinai scientists uncover link between influenza and heart disease

Study finds outdated Medicare rule delays nursing care, wastes hospital resources

Mortality among youth and young adults with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or cerebral palsy

Risk factors for the development of food allergy in infants and children

Organizational factors to reattract nurses to hospital employment

What drives food allergies? New study pinpoints early-life factors that raise risk

Early diagnosis key to improving childhood cancer survival

Microbiomes interconnect on a planetary-scale, new study finds

Let’s get on pancreatic cancer’s nerves

Intermittent fasting cut Crohn’s disease activity by 40% and halved inflammation in randomized clinical trial

New study in JNCCN unlocks important information about how to treat recurring prostate cancer

Simple at-home tests for detecting cat, dog viruses

New gut-brain discovery offers hope for treating ALS and dementia

Cognitive speed training linked to lower dementia incidence up to 20 years later

Businesses can either lead transformative change or risk extinction: IPBES

Opening a new window on the brainstem, AI algorithm enables tracking of its vital white matter pathways

[Press-News.org] 'Junk DNA' drives embryonic developmentSanford-Burnham researchers discover that microRNAs play an important role in germ layer formation—the process that determines which cells become which organs during embryonic development