(Press-News.org) SAN FRANCISCO—Researchers have made a genetic analysis of the microbes living deep inside a deposit of Marcellus Shale at a hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," site, and uncovered some surprises.

They expected to find many tough microbes suited to extreme environments, such as those that derive from archaea, a domain of single-celled species sometimes found in high-salt environments, volcanoes, or hot springs. Instead, they found very few genetic biomarkers for archaea, and many more for species that derive from bacteria.

They also found that the populations of microbes changed dramatically over a short period of time, as some species perished during the fracking operation and others became more abundant. One—an as-yet-unidentified bacterium—actually prospered, and eventually made up 90 percent of the microbial population in fluids taken from the fracked well.

Researchers may never know the exact species of bacteria in the fluids because of the difficulty in replicating the subsurface conditions in the laboratory, and the challenges associated with culturing unknown microbes from such environments, explained Paula Mouser, assistant professor of civil, environmental and geodetic engineering at Ohio State University and lead author of the study.

"There are millions of microbes that we can detect using biomarkers, but haven't ever isolated or cultured from these environments before. Most are grouped into loose associations based on shared genetic characteristics—something akin to a human extended family," Mouser said.

"Probably, the best we'll be able to do is identify their microbial 'cousins.'"

The study tracked the microbe species found in the water pumped out of a typical fracking site over a period of months during its normal operation. The rock at the site was a type of shale known as Marcellus, named for the city in New York where it was first identified.

To Mouser, the real value of the study is the new knowledge it offers on how microbes in fracking fluids compete and survive when the fluids are injected to the deep subsurface, as certain microbes could prove detrimental to oil and gas quality, or compromise well integrity.

She presented her team's initial findings at the American Geophysical Union meeting this week.

"This kind of research is important, because everything we learn about subsurface microorganisms helps us understand ecology on Earth's surface," she said. "When water samples like this are shared, there is the potential for great discovery—this knowledge could open doors to new technology for improving gas extraction efficiency or for treating flowback fluids from these sites."

Because of the large cost for drilling and fracking one well—usually, millions of dollars—individual researchers must team together with industry for access to samples.

In fact, companies do not normally share the contents of their "flowback" fluids—the mix of water, oil, and gas that emerges from an active well—because they could reveal the proprietary mix of chemicals that the company is using to aid extraction.

The Ohio State study was able to take place only through a collaboration with the U.S. Department of Energy National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) in Pittsburgh. NETL is working with industry to study fracking technologies and provided Mouser's team with water samples donated by an unnamed shale gas operation.

When it comes to energy extraction, tiny microbes play a huge role, Mouser said.

As it happens, the chemicals that companies pump into the ground along with water to help fracture shale and release petroleum contain carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous—in chemical formulations that microbes like to eat. So, left unchecked, the microbes in a fracking well can grow and reproduce out of control—so much so, that they may clog the fractures and block extraction, or foul the gas and oil with their waste, which contains sulfur.

This is no news to oil companies, Mouser added. They've long known about the microbes, and add biocides to the water to control the population. What isn't known: exactly what kinds of microbes live there, and what altering their populations does to the environment.

"Our goal is really to understand the physiology of the microbes and their biogeochemical role in the environment, to examine how industry practices influence subsurface microbial life and water quality," Mouser said.

Maryam Ansari, a master's student in environmental sciences at Ohio State, sequenced the microbes' DNA, and separated them into taxa, or taxonomic units—groups that could be thought of as microbial "cousins."

Of the 40 taxa the researchers identified from water samples taken at the start of the fracking operation, only six survived the first few weeks. Almost all of the bacteria at the site were classified as "halo-tolerant," similar to bacteria that live in deep saltwater environments.

Only the as-yet-unclassified bacterium, a halo-tolerant species, flourished; it eventually made up 90 percent of the surviving microbial population. Mouser is working with Professor Chuck Daniels in the Department of Microbiology to isolate and culture all the dominant organisms in the fluids.

The study is just beginning, and Mouser hopes that as they learn more, the researchers will be able to pin down how the microbes metabolize fracking fluids.

Ultimately, they hope to meld those discoveries with a computer model that can predict fluid movement from shale formations to groundwater aquifers. The model would provide tools for commercial companies to assess the safety of possible fracking sites.

In the meantime, Mouser is very interested in teaming with other industry partners to also look at microbial dynamics in a different kind of rock: Ohio's Utica Shale.

Ohio State's Subsurface Energy Resource Center funded the genomic analyses, which were done at the university's Plant Microbe Genetics Facility. These early findings have earned Mouser a new grant from the National Science Foundation so that she can pursue the work further.

###

Contact: Paula Mouser, (614) 247-4429; Mouser.19@osu.edu

Written by Pam Frost Gorder, (614) 292-9475; Gorder.1@osu.edu

Editor's note: to reach Mouser during the American Geophysical Union meeting, contact Pam Frost Gorder.

DNA analysis of microbes in a fracking site yields surprises

2012-12-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Multitasking plasmonic nanobubbles kill some cells, modify others

2012-12-04

HOUSTON – (Dec. 3, 2012) – Researchers at Rice University have found a way to kill some diseased cells and treat others in the same sample at the same time. The process activated by a pulse of laser light leaves neighboring healthy cells untouched.

The unique use for tunable plasmonic nanobubbles developed in the Rice lab of Dmitri Lapotko shows promise to replace several difficult processes now used to treat cancer patients, among others, with a fast, simple, multifunctional procedure.

The research is the focus of a paper published online this week by the American ...

Listen up, doc: Empathy raises patients' pain tolerance

2012-12-04

A doctor-patient relationship built on trust and empathy doesn't just put patients at ease – it actually changes the brain's response to stress and increases pain tolerance, according to new findings from a Michigan State University research team.

Medical researchers have shown in recent studies that doctors who listen carefully have happier patients with better health outcomes, but the underlying mechanism was unknown, said Issidoros Sarinopoulos, professor of radiology at MSU.

"This is the first study that has looked at the patient-centered relationship from a neurobiological ...

Women with sleep apnea have higher degree of brain damage than men, UCLA study shows

2012-12-04

Women suffering from sleep apnea have, on the whole, a higher degree of brain damage than men with the disorder, according to a first-of-its-kind study conducted by researchers at the UCLA School of Nursing. The findings are reported in the December issue of the peer-reviewed journal SLEEP.

Obstructive sleep apnea is a serious disorder that occurs when a person's breathing is repeatedly interrupted during sleep, sometimes hundreds of times. Each time, the oxygen level in the blood drops, eventually resulting in damage to many cells in the body. If left untreated, it ...

Mercury releases contaminate ocean fish: Dartmouth-led effort publishes major findings

2012-12-04

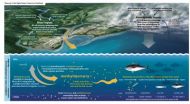

In new research published in a special issue of the journal Environmental Health Perspectives and in "Sources to Seafood: Mercury Pollution in the Marine Environment"— a companion report by the Dartmouth-led Coastal and Marine Mercury Ecosystem Research Collaborative (C-MERC), scientists report that mercury released into the air and then deposited into oceans contaminates seafood commonly eaten by people in the U.S. and globally.

Over the past century, mercury pollution in the surface ocean has more than doubled, as a result of past and present human activities such ...

Baby's health is tied to mother's value for family

2012-12-04

The value that an expectant mother places on family—regardless of the reality of her own family situation—predicts the birthweight of her baby and whether the child will develop asthma symptoms three years later, according to new research from USC.

The findings suggest that one's culture is a resource that can provide tangible physical health benefits.

"We know that social support has profound health implications; yet, in this case, this is more a story of beliefs than of actual family support," said Cleopatra Abdou, assistant professor at the USC Davis School of Gerontology.

Abdou ...

University of Minnesota researchers find new target for Alzheimer's drug development

2012-12-04

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (December 3, 2012) – Researchers at the University of Minnesota's Center for Drug Design have developed a synthetic compound that, in a mouse model, successfully prevents the neurodegeneration associated with Alzheimer's disease.

In the pre-clinical study, researchers Robert Vince, Ph.D.; Swati More, Ph.D.; and Ashish Vartak, Ph.D., of the University's Center for Drug Design, found evidence that a lab-made compound known as psi-GSH enables the brain to use its own protective enzyme system, called glyoxalase, against the Alzheimer's disease process. ...

Western University researchers make breakthrough in arthritis research

2012-12-04

Researchers at Western University have made a breakthrough that could lead to a better understanding of a common form of arthritis that, until now, has eluded scientists.

According to The Arthritis Society, the second most common form of arthritis after osteoarthritis is "diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis" or DISH. It affects between six and 12 percent of North Americans, usually people older than 50. DISH is classified as a form of degenerative arthritis and is characterized by the formation of excessive mineral deposits along the sides of the vertebrae in the ...

New Jamaica butterfly species emphasizes need for biodiversity research

2012-12-04

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — University of Florida scientists have co-authored a study describing a new Lepidoptera species found in Jamaica's last remaining wilderness.

Belonging to the family of skipper butterflies, the new genus and species is the first butterfly discovered in Jamaica since 1995. Scientists hope the native butterfly will encourage conservation of the country's last wilderness where it was discovered: the Cockpit Country. The study appearing in today's Tropical Lepidoptera Research, a bi-annual print journal, underscores the need for further biodiversity research ...

Managing care and competition

2012-12-04

Medicare Advantage (MA), with more than 10 million enrollees, is the largest alternative to traditional Medicare. MA's managed care approach was designed to provide coordinated, integrated care for patients and savings for taxpayers, but since the program launched as Medicare Part C in 1985, critics have said that the system limited enrollee freedom of choice without significant benefit or savings to the Medicare program. They also pointed to the tendency of some private payers to design benefit plans and marketing campaigns that attracted healthier patients, leaving sicker, ...

New study shows probiotics help fish grow up faster and healthier

2012-12-04

BALTIMORE, MD (December 3, 2012)— Probiotics like those found in yogurt are not only good for people--they are also good for fish. A new study by scientists at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology found that feeding probiotics to baby zebrafish accelerated their development and increased their chances of survival into adulthood.

This research could help increase the success of raising rare ornamental fish to adulthood. It also has implications for aquaculture, since accelerating the development of fish larvae--the toughest time for survival--could mean ...