(Press-News.org) SAN FRANCISCO—Scattered around the Milky Way are stars that resemble our own sun—but a new study is finding that any planets orbiting those stars may very well be hotter and more dynamic than Earth.

That's because the interiors of any terrestrial planets in these systems are likely warmer than Earth—up to 25 percent warmer, which would make them more geologically active and more likely to retain enough liquid water to support life, at least in its microbial form.

The preliminary finding comes from geologists and astronomers at Ohio State University who have teamed up to search for alien life in a new way.

They studied eight "solar twins" of our sun—stars that very closely match the sun in size, age, and overall composition—in order to measure the amounts of radioactive elements they contain. Those stars came from a dataset recorded by the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher spectrometer at the European Southern Observatory in Chile.

They searched the solar twins for elements such as thorium and uranium, which are essential to Earth's plate tectonics because they warm our planet's interior. Plate tectonics helps maintain water on the surface of the Earth, so the existence of plate tectonics is sometimes taken as an indicator of a planet's hospitality to life.

Of the eight solar twins they've studied so far, seven appear to contain much more thorium than our sun—which suggests that any planets orbiting those stars probably contain more thorium, too. That, in turn, means that the interior of the planets are probably warmer than ours.

For example, one star in the survey contains 2.5 times more thorium than our sun, said Ohio State doctoral student Cayman Unterborn. According to his measurements, terrestrial planets that formed around that star probably generate 25 percent more internal heat than Earth does, allowing for plate tectonics to persist longer through a planet's history, giving more time for live to arise.

"If it turns out that these planets are warmer than we previously thought, then we can effectively increase the size of the habitable zone around these stars by pushing the habitable zone farther from the host star, and consider more of those planets hospitable to microbial life," said Unterborn, who presented the results at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco this week.

"At this point, all we can say for sure is that there is some natural variation in the amount of radioactive elements inside stars like ours," he added. "With only nine samples including the sun, we can't say much about the full extent of that variation throughout the galaxy. But from what we know about planet formation, we do know that the planets around those stars probably exhibit the same variation, which has implications for the possibility of life."

His advisor, Wendy Panero, associate professor in the School of Earth Sciences at Ohio State, explained that radioactive elements such as thorium, uranium, and potassium are present within Earth's mantle. These elements heat the planet from the inside, in a way that is completely separate from the heat emanating from Earth's core.

"The core is hot because it started out hot," Panero said. "But the core isn't our only heat source. A comparable contributor is the slow radioactive decay of elements that were here when the Earth formed. Without radioactivity, there wouldn't be enough heat to drive the plate tectonics that maintains surface oceans on Earth."

The relationship between plate tectonics and surface water is complex and not completely understood. Panero called it "one of the great mysteries in the geosciences." But researchers are beginning to suspect that the same forces of heat convection in the mantle that move Earth's crust somehow regulate the amount of water in the oceans, too.

"It seems that if a planet is to retain an ocean over geologic timescales, it needs some kind of crust 'recycling system,' and for us that's mantle convection," Unterborn said.

In particular, microbial life on Earth benefits from subsurface heat. Scores of microbes known as archaea do not rely on the sun for energy, but instead live directly off of heat arising from deep inside the Earth.

On Earth, most of the heat from radioactive decay comes from uranium. Planets rich in thorium, which is more energetic than uranium and has a longer half-life, would "run" hotter and remain hot longer, he said, which gives them more time to develop life.

As to why our solar system has less thorium, Unterborn said it's likely the luck of the draw.

"It all starts with supernovae. The elements created in a supernova determine the materials that are available for new stars and planets to form. The solar twins we studied are scattered around the galaxy, so they all formed from different supernovae. It just so happens that they had more thorium available when they formed than we did."

Jennifer Johnson, associate professor of astronomy at Ohio State and co-author of the study, cautioned that the results are preliminary. "All signs are pointing to yes—that there is a difference in the abundance of radioactive elements in these stars, but we need to see how robust the result is," she said.

Next, Unterborn wants to do a detailed statistical analysis of noise in the HARPS data to improve the accuracy of his computer models. Then he will seek telescope time to look for more solar twins.

###

This research was funded by Panero's CAREER award from the National Science Foundation.

Contact: Wendy Panero, (614) 292-6290; Panero.1@osu.edu

Cayman Unterborn, Unterborn.1@osu.edu

Written by Pam Frost Gorder, (614) 292-9475; Gorder.1@osu.edu

Editor's note: Panero is not attending AGU and will best be reached in her office. Unterborn is best reached by email, or through Pam Frost Gorder.

Search for life suggests solar systems more habitable than ours

2012-12-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

DNA analysis of microbes in a fracking site yields surprises

2012-12-04

SAN FRANCISCO—Researchers have made a genetic analysis of the microbes living deep inside a deposit of Marcellus Shale at a hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," site, and uncovered some surprises.

They expected to find many tough microbes suited to extreme environments, such as those that derive from archaea, a domain of single-celled species sometimes found in high-salt environments, volcanoes, or hot springs. Instead, they found very few genetic biomarkers for archaea, and many more for species that derive from bacteria.

They also found that the populations of microbes ...

Multitasking plasmonic nanobubbles kill some cells, modify others

2012-12-04

HOUSTON – (Dec. 3, 2012) – Researchers at Rice University have found a way to kill some diseased cells and treat others in the same sample at the same time. The process activated by a pulse of laser light leaves neighboring healthy cells untouched.

The unique use for tunable plasmonic nanobubbles developed in the Rice lab of Dmitri Lapotko shows promise to replace several difficult processes now used to treat cancer patients, among others, with a fast, simple, multifunctional procedure.

The research is the focus of a paper published online this week by the American ...

Listen up, doc: Empathy raises patients' pain tolerance

2012-12-04

A doctor-patient relationship built on trust and empathy doesn't just put patients at ease – it actually changes the brain's response to stress and increases pain tolerance, according to new findings from a Michigan State University research team.

Medical researchers have shown in recent studies that doctors who listen carefully have happier patients with better health outcomes, but the underlying mechanism was unknown, said Issidoros Sarinopoulos, professor of radiology at MSU.

"This is the first study that has looked at the patient-centered relationship from a neurobiological ...

Women with sleep apnea have higher degree of brain damage than men, UCLA study shows

2012-12-04

Women suffering from sleep apnea have, on the whole, a higher degree of brain damage than men with the disorder, according to a first-of-its-kind study conducted by researchers at the UCLA School of Nursing. The findings are reported in the December issue of the peer-reviewed journal SLEEP.

Obstructive sleep apnea is a serious disorder that occurs when a person's breathing is repeatedly interrupted during sleep, sometimes hundreds of times. Each time, the oxygen level in the blood drops, eventually resulting in damage to many cells in the body. If left untreated, it ...

Mercury releases contaminate ocean fish: Dartmouth-led effort publishes major findings

2012-12-04

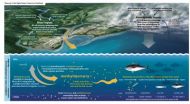

In new research published in a special issue of the journal Environmental Health Perspectives and in "Sources to Seafood: Mercury Pollution in the Marine Environment"— a companion report by the Dartmouth-led Coastal and Marine Mercury Ecosystem Research Collaborative (C-MERC), scientists report that mercury released into the air and then deposited into oceans contaminates seafood commonly eaten by people in the U.S. and globally.

Over the past century, mercury pollution in the surface ocean has more than doubled, as a result of past and present human activities such ...

Baby's health is tied to mother's value for family

2012-12-04

The value that an expectant mother places on family—regardless of the reality of her own family situation—predicts the birthweight of her baby and whether the child will develop asthma symptoms three years later, according to new research from USC.

The findings suggest that one's culture is a resource that can provide tangible physical health benefits.

"We know that social support has profound health implications; yet, in this case, this is more a story of beliefs than of actual family support," said Cleopatra Abdou, assistant professor at the USC Davis School of Gerontology.

Abdou ...

University of Minnesota researchers find new target for Alzheimer's drug development

2012-12-04

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (December 3, 2012) – Researchers at the University of Minnesota's Center for Drug Design have developed a synthetic compound that, in a mouse model, successfully prevents the neurodegeneration associated with Alzheimer's disease.

In the pre-clinical study, researchers Robert Vince, Ph.D.; Swati More, Ph.D.; and Ashish Vartak, Ph.D., of the University's Center for Drug Design, found evidence that a lab-made compound known as psi-GSH enables the brain to use its own protective enzyme system, called glyoxalase, against the Alzheimer's disease process. ...

Western University researchers make breakthrough in arthritis research

2012-12-04

Researchers at Western University have made a breakthrough that could lead to a better understanding of a common form of arthritis that, until now, has eluded scientists.

According to The Arthritis Society, the second most common form of arthritis after osteoarthritis is "diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis" or DISH. It affects between six and 12 percent of North Americans, usually people older than 50. DISH is classified as a form of degenerative arthritis and is characterized by the formation of excessive mineral deposits along the sides of the vertebrae in the ...

New Jamaica butterfly species emphasizes need for biodiversity research

2012-12-04

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — University of Florida scientists have co-authored a study describing a new Lepidoptera species found in Jamaica's last remaining wilderness.

Belonging to the family of skipper butterflies, the new genus and species is the first butterfly discovered in Jamaica since 1995. Scientists hope the native butterfly will encourage conservation of the country's last wilderness where it was discovered: the Cockpit Country. The study appearing in today's Tropical Lepidoptera Research, a bi-annual print journal, underscores the need for further biodiversity research ...

Managing care and competition

2012-12-04

Medicare Advantage (MA), with more than 10 million enrollees, is the largest alternative to traditional Medicare. MA's managed care approach was designed to provide coordinated, integrated care for patients and savings for taxpayers, but since the program launched as Medicare Part C in 1985, critics have said that the system limited enrollee freedom of choice without significant benefit or savings to the Medicare program. They also pointed to the tendency of some private payers to design benefit plans and marketing campaigns that attracted healthier patients, leaving sicker, ...