(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. – Molecular chaperones have emerged as exciting new potential drug targets, because scientists want to learn how to stop cancer cells, for example, from using chaperones to enable their uncontrolled growth. Now a team of biochemists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst led by Lila Gierasch have deciphered key steps in the mechanism of the Hsp70 molecular machine by "trapping" this chaperone in action, providing a dynamic snapshot of its mechanism.

She and colleagues describe this work in the current issue of Cell. Gierasch's research on Hsp70 chaperones is supported by a long-running grant to her lab from NIH's National Institute for General Medical Sciences.

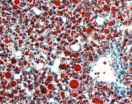

Molecular chaperones like the Hsp70s facilitate the origami-like folding of proteins, made in the cell's nanofactories or ribosomes, from where they emerge unstructured like noodles. Proteins only function when folded into their proper structures, but the process is so difficult under cellular conditions that molecular chaperone helpers are needed.

The newly discovered information about chaperone action is important because all rapidly dividing cells use a lot of Hsp70, Gierasch points out. "The saying is that cancer cells are addicted to Hsp70 because they rely on this chaperone for explosive new cell growth. Cancer shifts our body's production of Hsp70 into high gear. If we can figure out a way to take that away from cancer cells, maybe we can stop the out-of-control tumor growth. To find a molecular way to inhibit Hsp70, you've got to know how it works and what it needs to function, so you can identify its vulnerabilities."

Chaperone proteins in cells, from bacteria to humans, act like midwives or bodyguards, protecting newborn proteins from misfolding and existing proteins against loss of structure caused by stress such as heat or a fever. In fact, the heat shock protein (Hsp) group includes a variety of chaperones active in both these situations.

As Gierasch explains, "New proteins emerge into a challenging environment. It's very crowded in the cell and it would be easy for them to get their sticky amino acid chains tangled and clumped together. Chaperones bind to them and help to avoid this aggregation, which is implicated in many pathologies such as neurodegenerative diseases. This role of chaperones has also heightened interest in using them therapeutically."

However, chaperones must not bind too tightly or a protein can't move on to do its job. To avoid this, chaperones rapidly cycle between tight and loose binding states, determined by whether ATP or ADP is bound. In the loose state, a protein client is free to fold or to be picked up by another chaperone that will help it fold to do its cellular work. In effect, Gierasch says, Hsp70s create a "holding pattern" to keep the protein substrate viable and ready for use, but also protected.

She and colleagues knew the Hsp70's structure in both tight and loose binding affinity states, but not what happened between, which is essential to understanding the mechanism of chaperone action. Using the analogy of a high jump, they had a snapshot of the takeoff and landing, but not the top of the jump. "Knowing the end points doesn't tell us how it works. There is a shape change in there that we wanted to see," Gierasch says.

To address this, she and her colleagues postdoctoral fellows Anastasia Zhuravleva and Eugenia Clerico obtained "fingerprints" of the structure of Hsp70 in different states by using state-of-the-art nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods that allowed them to map how chemical environments of individual amino acids of the protein change in different sample conditions. Working with an Hsp70 known as DnaK from E. coli bacteria, Zhuravleva and Clerico assigned its NMR spectra. In other words, they determined which peaks came from which amino acids in this large molecule.

The UMass Amherst team then mutated the Hsp70 so that cycling between tight and loose binding states stopped. As Gierasch explains, "Anastasia and Eugenia were able to stop the cycle part-way through the high jump, so to speak, and obtain the molecular fingerprint of a transient intermediate." She calls this accomplishment "brilliant."

Now that the researchers have a picture of this critical allosteric state, that is, one in which events at one site control events in another, Gierasch says many insights emerge. For example, it appears nature uses this energetically tense state to "tune" alternate versions of Hsp70 to perform different cellular functions. "Tuning means there may be evolutionary changes that let the chaperone work with its partners optimally," she notes.

"And if you want to make a drug that controls the amount of Hsp70 available to a cell, our work points the way toward figuring out how to tickle the molecule so you can control its shape and its ability to bind to its client. We're not done, but we made a big leap," Gierasch adds. "We now have a idea of what the Hsp70 structure is when it is doing its job, which is extraordinarily important."

INFORMATION:

Biochemists trap a chaperone machine in action

2012-12-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Image of the Carina Nebula marks inauguration of VLT Survey Telescope

2012-12-06

The latest telescope at ESO's Paranal Observatory in Chile -- the VLT Survey Telescope (VST) -- was inaugurated today at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) Observatory of Capodimonte, in Naples, Italy. The ceremony was attended by the Mayor of Naples, Luigi De Magistris, the INAF President, Giovanni Bignami, the ESO representatives Bruno Leibundgut and Roberto Tamai, and the main promoter of the telescope, Massimo Capaccioli of the University of Naples Federico II and INAF.

The VST is a state-of-the-art 2.6-metre telescope, with the huge 268-megapixel ...

Research on blood vessel proteins holds promise for controlling 'blood-brain barrier'

2012-12-06

Working with mice, Johns Hopkins researchers have shed light on the activity of a protein pair found in cells that form the walls of blood vessels in the brain and retina, experiments that could lead to therapeutic control of the blood-brain barrier and of blood vessel growth in the eye.

Their work reveals a dual role for the protein pair, called Norrin/Frizzled-4, in managing the blood vessel network that serves the brain and retina. The first job of the protein pair's signaling is to form the network's proper 3-D architecture in the retina during fetal development. ...

Immune system kill switch could be target for chemotherapy and infection recovery

2012-12-06

Researchers have discovered an immune system 'kill switch' that destroys blood stem cells when the body is under severe stress, such as that induced by chemotherapy and systemic infections.

The discovery could have implications for protecting the blood system during chemotherapy or in diseases associated with overwhelming infection, such as sepsis.

The kill switch is triggered when internal immune cell signals that protect the body from infection go haywire. Dr Seth Masters, Dr Motti Gerlic, Dr Benjamin Kile and Dr Ben Croker from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute ...

Nobody's perfect

2012-12-06

Researchers at Cambridge and Cardiff have found that, on average, a normal healthy person carries approximately 400 potentially damaging DNA variants and two variants known to be associated directly with disease traits. They showed that one in ten people studied is expected to develop a genetic disease as a consequence of carrying these variants.

It has been known for decades that all people carry some damaging genetic variants that appear to cause little or no ill effect. But this is the first time that researchers have been able to quantify how many such variants each ...

Overestimation of abortion deaths in Mexico hinders maternal mortality reduction efforts

2012-12-06

This press release is available in Spanish and Portuguese.

A collaborative study conducted in Mexico by researchers of the University of West Virginia-Charleston (USA), Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla (Mexico), Universidad de Chile and the Institute of Molecular Epidemiology of the Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción (Chile), revealed that IPAS-Mexico overestimated rates of maternal and abortion mortality up to 35% over the last two decades. The research, recently published in the International Journal of Women's Health highlights that Mexico ...

Researchers discover regulator linking exercise to bigger, stronger muscles

2012-12-06

BOSTON - Scientists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have isolated a previously unknown protein in muscles that spurs their growth and increased power following resistance exercise. They suggest that artificially raising the protein's levels might someday help prevent muscle loss caused by cancer, prolonged inactivity in hospital patients, and aging.

Mice given extra doses of the protein gained muscle mass and strength, and rodents with cancer were much less affected by cachexia, the loss of muscle that often occurs in cancer patients, according to the report in the Dec. ...

A relationship between cancer genes and the reprogramming gene SOX2 discovered

2012-12-06

A team of researchers from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), led by Manuel Serrano, from the Tumour Suppression Group, together with scientists from London and Santiago de Compostela, has discovered that the cellular reprogramming gene SOX2, which is involved in several types of cancers, such as lung cancer and pituitary cancer, is directly regulated by the tumor suppressor CDKN1B(p27) gene, which is also associated with these types of cancer.

The same edition of the online version of the journal also includes a study led by Massimo Squatrito, who recently ...

Study IDs gene that turns carbs into fat

2012-12-06

Berkeley — A gene that helps the body convert that big plate of holiday cookies you just polished off into fat could provide a new target for potential treatments for fatty liver disease, diabetes and obesity.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, are unlocking the molecular mechanisms of how our body converts dietary carbohydrates into fat, and as part of that research, they found that a gene with the catchy name BAF60c contributes to fatty liver, or steatosis.

In the study, to be published online Dec. 6 in the journal Molecular Cell, the researchers ...

ACNP: Novel NMDA receptor modulator significantly reduces depression scores within hours

2012-12-06

HOLLYWOOD, FL and EVANSTON, IL, December 6, 2012 -- Naurex Inc., a clinical stage company developing innovative treatments to address unmet needs in psychiatry and neurology, today reported positive results from a Phase IIa clinical trial of its lead antidepressant compound, GLYX-13. GLYX-13 is a novel partial agonist of the NMDA receptor. The Phase Ila results are being presented this week at the 51st Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP).

The Phase IIa results show that a single administration of GLYX-13 produced statistically significant ...

Research yields understanding of Darwin's 'abominable mystery'

2012-12-06

Research by Indiana University paleobotanist David L. Dilcher and colleagues in Europe sheds new light on what Charles Darwin famously called "an abominable mystery": the apparently sudden appearance and rapid spread of flowering plants in the fossil record.

Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers present a scenario in which flowering plants, or angiosperms, evolved and colonized various types of aquatic environments over about 45 million years in the early to middle Cretaceous Period.

Dilcher is professor emeritus at IU Bloomington ...