New study sheds light on how Salmonella spreads in the body

Research could have major implications for improving treatment and vaccination

2012-12-07

(Press-News.org) Findings of Cambridge scientists, published today in the journal PLoS Pathogens, show a new mechanism used by bacteria to spread in the body with the potential to identify targets to prevent the dissemination of the infection process.

Salmonella enterica is a major threat to public health, causing systemic diseases (typhoid and paratyphoid fever), gastroenteritis and non-typhoidal septicaemia (NTS) in humans and in many animal species worldwide. In the natural infection, salmonellae are typically acquired from the environment by oral ingestion of contaminated water or food or by contact with a carrier. Current vaccines and treatments for S. enterica infections are not sufficiently effective, and there is a need to develop new therapeutic strategies.

Dr Andrew Grant, lead author of the study from the University of Cambridge, said: "A key unanswered question in infectious diseases is how pathogens such as Salmonella grow at the single-cell level and spread in the body. This gap in our knowledge is hampering our ability to target therapy and vaccines with accuracy."

During infection, salmonellae are found mainly within cells of the immune system where they are thought to grow and persist. To do so the bacteria adapt to their surrounding environment and resist the antimicrobial activity of the cell. Research from the Cambridge group has shown that the situation is more complex in that the bacteria must also escape from infected cells to spread to distant sites in the body, avoiding the local escalation of the immune response and thus playing a 'catch me if you can' game with the host immune system.

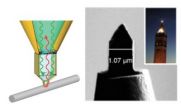

A body of knowledge has been built using in vitro (test tube) cell culture experiments that indicates that replication of Salmonella enterica within host cells in vitro is somewhat dependent on the bacteria making a syringe-like structure, called a Type 3 Secretory System (T3SS). This then injects bacterial proteins into the host cell, which in turn enhance bacterial replication inside that cell. This T3SS is encoded by genes in a region of the bacterial chromosome called Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 2 (or SPI-2). Translating this cell culture work into whole animals, it has become accepted dogma that the SPI-2 T3SS is also required for bacterial intracellular replication in cells inside the body.

However, using fluorescence and confocal microscopy (which are imaging techniques), the Cambridge team has dispelled this dogma concerning the requirement for the SPI-2 T3SS for intracellular replication in the body. The researchers have shown that mutants lacking SPI-2 can reach high numbers within individual host cells, a situation that does not happen in in vitro cell culture.

The researchers, from the Mastroeni and Maskell laboratories at the University of Cambridge's Department of Veterinary Medicine, investigated this phenomenon further and made the surprising discovery that salmonellae lacking the SPI-2 T3SS remain trapped inside cells and cannot spread in the body. One idea is that this will in turn lead to the arrest of bacterial division as a consequence of spatial or nutritional constraints. Despite growing to high numbers per cell, these mutants are much less able to grow overall in the body because far fewer cells become infected due to the greatly reduced ability of the bacteria to escape from the original infected cells.

These findings call into question the usefulness of some in vitro experimental systems that, when used in isolation, do not usefully represent the very complex structure of mammalian organisms.

The team also presented a new role for the NADPH phagocyte oxidase (Phox) (a host mechanism which generates reactive oxygen species which can inhibit the growth and/or kill the bacteria) in the control of Salmonella infection. They observed that this system inhibits bacterial escape from host cells, and that normally the SPI-2-encoded T3SS counters this system to facilitate bacterial exit from infected cells. This highlights a previously unknown interplay between SPI-2 T3SS and innate immunity in the dynamics of within-host bacterial growth and spread. The research shows that in the absence of an active Phox, SPI-2 T3SS becomes dispensable for the spread of Salmonella in the tissues. Conversely, when an active Phox is present, a SPI-2 T3SS mutant grows inside cells to high intracellular densities but appears to be unable to escape from the cells and disseminate in the body.

Dr Grant said: "Salmonella is a significant public health threat. Unfortunately, effective treatments and vaccinations have thus far eluded scientists, in part because of a lack of understanding of how and why the bacteria spread. This research provides critical insight which will hopefully lead to new medical interventions for this disease."

###For additional information please contact:

Office of Communications, University of Cambridge

Tel: +44 (0) 1223 332300

Email: communications@admin.cam.ac.uk

Notes to editors:

1. The paper 'Attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium Lacking the Pathogenicity Island -2 Type 3 Secretion System Grow to High Bacterial Numbers inside Phagocytes in Mice' will be published in the 06 December 2012 edition of PLoS Pathogens.

2. The work was funded by the Medical Research Council, grant G0801161, awarded to Dr Andrew Grant, Dr Piero Mastroeni and Prof. Duncan Maskell.Dr T. J. McKinley was supported by the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs/Higher Education Funding Council of England (grant number VT0105). Dr Gemma Foster was supported by a Wellcome Trust PhD training studentship.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2012-12-07

A century after the world's first ultrasonic detection device – invented in response to the sinking of the Titanic – Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute scientists have provided the first neurophysiological evidence for something that researchers have long suspected: ultrasound applied to the periphery, such as the fingertips, can stimulate different sensory pathways leading to the brain.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. The discovery carries implications for diagnosing and treating neuropathy, which affects millions of people around the world.

"Ideally, ...

2012-12-07

Researchers from North Carolina State University, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and a host of other institutions have developed a safety testing system to help chemists design inherently safer chemicals and processes.

The innovative "TiPED" testing system (Tiered Protocol for Endocrine Disruption) stems from a cross-disciplinary collaboration among scientists, and can be applied at different phases of the chemical design process. The goal of the system is to help steer companies away from inadvertently creating harmful products, and thus avoid ...

2012-12-07

PORTLAND, Ore. — Researchers at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) have found that adults with autism, who represent about 1 percent of the adult population in the United States, report significantly worse health care experiences than their non-autistic counterparts.

"Like other adults, adults on the autism spectrum need to use health care services to prevent and treat illness. As a primary care provider, I know that our health care system is not always set up to offer high-quality care to adults on the spectrum; however, I was saddened to see how large the disparities ...

2012-12-07

Galveston, Texas — Stillbirth is a tragedy that occurs in one of every 160 births in the United States. Compounding the sadness for many families, the standard medical test used to examine fetal chromosomes often can't pin down what caused their baby to die in utero. In most cases, the cause of the stillbirth is not immediately known. The traditional way to determine what happened is to examine the baby's chromosomes using a technique called karyotyping. This method leaves much to be desired because, in many cases, it fails to provide any result at all. Today, some 25 to ...

2012-12-07

Highlanders in Tibet and Ethiopia share a biological adaptation that enables them to thrive in the low oxygen of high altitudes, but the ability to pass on the trait appears to be linked to different genes in the two groups, research from a Case Western Reserve University scientist and colleagues shows.

The adaptation is the ability to maintain a relatively low (for high altitudes) level of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Members of ethnic populations - such as most Americans - who historically live at low altitudes naturally respond to the ...

2012-12-07

EVANSTON, Ill. --- With a little practice, one could learn to tell a lie that may be indistinguishable from the truth.

New Northwestern University research shows that lying is more malleable than previously thought, and with a certain amount of training and instruction, the art of deception can be perfected.

People generally take longer and make more mistakes when telling lies than telling the truth, because they are holding two conflicting answers in mind and suppressing the honest response, previous research has shown. Consequently, researchers in the present study ...

2012-12-07

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—December 6, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have identified a novel mechanism by which a type of low-carb, low-calorie diet—called a "ketogenic diet"—could delay the effects of aging. This fundamental discovery reveals how such a diet could slow the aging process and may one day allow scientists to better treat or prevent age-related diseases, including heart disease, Alzheimer's disease and many forms of cancer.

As the aging population continues to grow, age-related illnesses have become increasingly common. Already in the United States, ...

2012-12-07

SAN ANTONIO, TX (December 6, 2012)—Women are more likely to follow experts' advice on how to reduce their risk of an important side effect of breast cancer surgery—like lymphedema—if they feel confident in their abilities and know how to manage stress, according to new research from Fox Chase Cancer Center to be presented at the 2012 CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Saturday, December 8, 2012.

These findings suggest that clinicians must do more than just inform women of the ways they should change their behavior, says Suzanne M. Miller, PhD, Professor ...

2012-12-07

If nanoscience were television, we'd be in the 1950s. Although scientists can make and manipulate nanoscale objects with increasingly awesome control, they are limited to black-and-white imagery for examining those objects. Information about nanoscale chemistry and interactions with light—the atomic-microscopy equivalent to color—is tantalizingly out of reach to all but the most persistent researchers.

But that may all change with the introduction of a new microscopy tool from researchers at the Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley ...

2012-12-07

Be careful what you eat, says University of Notre Dame stream ecologist Gary Lamberti.

If you're catching and eating fish from a Lake Michigan tributary with a strong salmon run, the stream fish — brook trout, brown trout, panfish — may be contaminated by pollutants carried in by the salmon.

Research by Lamberti, professor and chair of biology, and his laboratory has revealed that salmon, as they travel upstream to spawn and die, carry industrial pollutants into Great Lakes streams and tributaries. The research was recently published in the journal Environmental Science ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New study sheds light on how Salmonella spreads in the body

Research could have major implications for improving treatment and vaccination