(Press-News.org) ARGONNE, Ill. – For the first time, scientists witnessed the details of the full, ultrafast process of liquid droplets evolving into a bubble when they strike a surface. Their research determined that surface wetness affects the bubble's fate.

This research could one day help eliminate bubbles formed during spray coating, metal casting and ink-jet printing. It also could impact studies on fuel efficiency and engine life by understanding the splashing caused by fuel hitting engine walls.

"How liquid coalesces into a drop or breaks up into a splash when hitting something solid is a fundamental problem in the study of fluid dynamics," said Jung Ho Je, one of the lead authors on the result "How Does an Air Film Evolve into a Bubble During Drop Impact?", published in the journal Physical Review Letters, and a physicist at Pohang University of Science and Technology in Korea.

A team of Korean and U.S. scientists used the Advanced Photon Source at the Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory to profile the film of air that gets trapped between a droplet and a surface and to study how it evolves into a bubble. Visualizing this process required the use of ultrafast X-ray phase-contrast imaging done at the APS's 32-ID beamline. The APS is the only synchrotron light source currently providing this technique, which is key for bubble research.

The bubble formation was captured at a speed of 271,000 frames per second. For comparison, a camera needs to shoot at 600 frames per second to capture a bullet fired from a .38 Smith & Wesson Special handgun.

"This is the first time we can clearly visualize the detailed profile of air dynamics inside of a droplet, which made understanding what forces are at play much easier," said Kamel Fezzaa, a physicist working at the APS.

It is known that the surrounding air pressure influences splashing, but it also leaves an air layer under the drop that evolves into a bubble. The researchers found that a sweet spot exists for controlling whether the emerging bubbles stay attached to the substrate or detach and float away. This sweet spot is a combination of the wetness of the surface material and the fluid properties of the droplet.

X-rays are an ideal tool for studying bubble formation. Visual-light imaging techniques have proved challenging because of reflection and refraction problems, and interferometry and total internal-reflection microscopy techniques can't track changes in the air thickness. Scientists used the APS's unique combination of phase-contrast imaging and ability to take 0.5 microsecond snapshots at intervals of 3.68 microseconds, or 3.68 millionths of a second, to create a new technique for tracking changes at the interface of air and liquid in real time.

Numerous studies during the last few years have revealed the trapped air under the droplet, but this is the first time the bubble profile and cause of collapse has been visualized and explained. The planned APS upgrade will enable viewing of even faster occurrences and a wider field of view to capture the droplet and smaller bubble formation in the same video.

In future experiments, scientists plan to test whether other conditions such as the temperature of the impact surface or the pressure and nature of surrounding gases affect the bubble formation.

###

The research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea. The APS is supported by DOE's Office of Science.

The Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory is one of five national synchrotron radiation light sources supported by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science to carry out applied and basic research to understand, predict, and ultimately control matter and energy at the electronic, atomic, and molecular levels, provide the foundations for new energy technologies, and support DOE missions in energy, environment, and national security. To learn more about the Office of Science X-ray user facilities, visit the user facilities directory.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy'sOffice of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Images and video available at: http://www.anl.gov/articles/bubble-study-could-improve-industrial-splash-control

END

Prostate cancer patients receiving the costly treatment known as proton radiotherapy experienced minimal relief from side effects such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction, compared to patients undergoing a standard radiation treatment called intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), Yale School of Medicine researchers report in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Standard treatments for men with prostate cancer, such as radical prostatectomy and IMRT, are known for causing adverse side effects such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Proponents of ...

New research by a University of Alberta archeologist may lead to a rethinking of how, when and from where our ancestors left Africa.

U of A researcher and anthropology chair Pamela Willoughby's explorations in the Iringa region of southern Tanzania yielded fossils and other evidence that records the beginnings of our own species, Homo sapiens. Her research, recently published in the journal Quaternary International, may be key to answering questions about early human occupation and the migration out of Africa about 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, which led to modern humans ...

Peach growers in California may soon have better tools for saving water because of work by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists in Parlier, Calif.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist Dong Wang is evaluating whether infrared sensors and thermal technology can help peach growers decide precisely when to irrigate in California's San Joaquin Valley. ARS is USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency, and the research supports the USDA priority of promoting international food security.

Irrigation is the primary source of water for agriculture ...

The plague-causing bacteria Yersinia pestis evades detection and establishes a stronghold without setting off the body's early alarms.

New discoveries reported this week help explain how the stealthy agent of Black Death avoids tripping a self-destruct mechanism inside germ-destroying cells.

The authors of the study, appearing in the Dec. 13 issue of Cell Host & Microbe, are Dr. Christopher N. LaRock of the University of Washington Department of Microbiology and Dr. Brad Cookson, UW professor of microbiology and laboratory medicine.

Normally, certain defender cells ...

A venomous primate with two tongues would seem safe from the pet trade, but the big-eyed, teddy-bear face of the slow loris (Nycticebus sp.) has made them a target for illegal pet poachers throughout the animal's range in southeastern Asia and nearby islands. A University of Missouri doctoral student and her colleagues recently identified three new species of slow loris. The primates had originally been grouped with another species. Dividing the species into four distinct classes means the risk of extinction is greater than previously believed for the animals but could ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — On the road to smaller, high-performance electronics, University of Illinois researchers have smoothed one speed bump by shrinking a key, yet notoriously large element of integrated circuits.

Three-dimensional rolled-up inductors have a footprint more than 100 times smaller without sacrificing performance. The researchers published their new design paradigm in the journal Nano Letters.

"It's a new concept for old technology," said team leader Xiuling Li, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Illinois.

Inductors, ...

Black holes range from modest objects formed when individual stars end their lives to behemoths billions of times more massive that rule the centers of galaxies. A new study using data from NASA's Swift satellite and Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope shows that high-speed jets launched from active black holes possess fundamental similarities regardless of mass, age or environment. The result provides a tantalizing hint that common physical processes are at work.

"What we're seeing is that once any black hole produces a jet, the same fixed fraction of energy generates the ...

VIDEO:

NASA's TRMM satellite passed above an intensifying Tropical Cyclone Evan on Dec. 11 at 1759 UTC (12:59 p.m. EST/U.S.) and saw the tallest thunderstorms around Evan's center of circulation reached...

Click here for more information.

NASA satellites have been monitoring Tropical Cyclone Evan and providing data to forecasters who expected the storm to intensify. On Dec. 13, Evan had grown from a tropical storm into a cyclone as NASA satellites observed cloud formation, ...

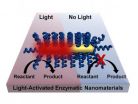

HOUSTON – (Dec. 13, 2012) – Since Edison's first bulb, heat has been a mostly undesirable byproduct of light. Now researchers at Rice University are turning light into heat at the point of need, on the nanoscale, to trigger biochemical reactions remotely on demand.

The method created by the Rice labs of Michael Wong, Ramon Gonzalez and Naomi Halas and reported today in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano makes use of materials derived from unique microbes – thermophiles – that thrive at high temperatures but shut down at room temperature.

The Rice project ...

CHAMPAIGN, lll. — Every time a human or bacterial cell divides it first must copy its DNA. Specialized proteins unzip the intertwined DNA strands while others follow and build new strands, using the originals as templates. Whenever these proteins encounter a break – and there are many – they stop and retreat, allowing a new cast of molecular players to enter the scene.

Scientists have long sought to understand how one of these players, a repair protein known as RecA in bacterial cells, helps broken DNA find a way to bridge the gap. They knew that RecA guided a broken ...